Foodways, a comparatively recent term, is the study of the procurement, preparation, and consumption of food. Put another way, foodways is the study of what people eat and why they eat it.

Traditional Foodways

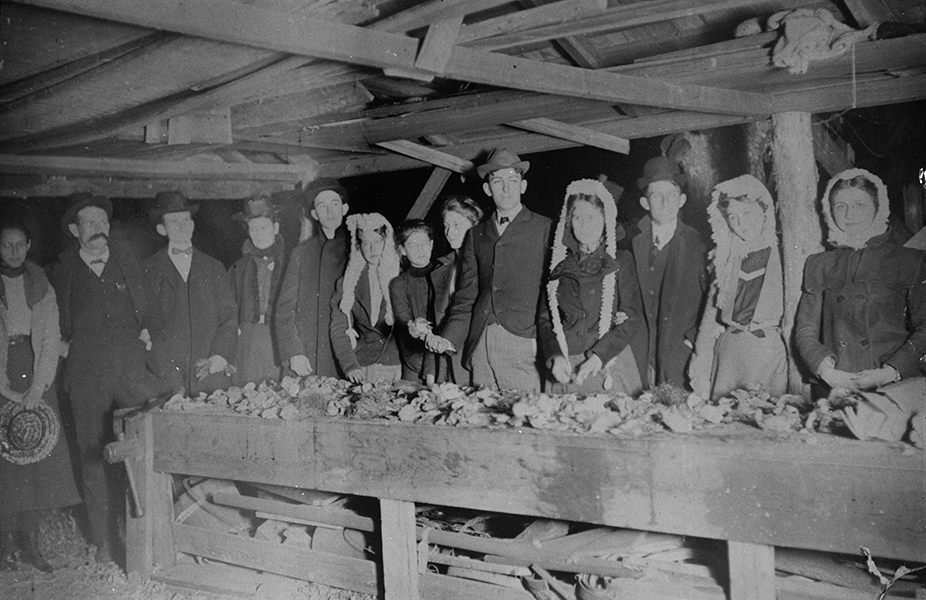

Before the arrival of white settlers, Creeks and Cherokees living in present-day Georgia had long cultivated corn, pounding and soaking kernels for use in porridgelike dishes and breads. Beans and peas were staples as well. Chestnuts and pecans were foraged and eaten out of hand, as were wild plums and blackberries. Along the coast, the waters teemed with shrimp and the mudflats were rife with oysters.

On the Georgia frontier, deer and bear, along with smaller game like squirrels and rabbits, were the primary meats. The typical meal was a one-pot affair, a hunters’ stew, cooked over an open flame. A large joint of meat might be thrown directly in the embers to roast. The availability of vegetables followed the dictates of the season: beans in the summer, green corn in the fall.

The Spanish introduced pigs to Florida in 1539. The animals later made their appearance in Georgia, where they came to be appreciated for their efficient conversion of feed to flesh. Pigs also foraged for food, while pastoral cattle proved to be more expensive to feed. “If the 'king’ of the antebellum southern economy were cotton,” geographer Sam Bowers Hilliard writes in Hog Meat and Hoecake, “then the title of 'queen’ must go to the pig.” Indeed, pork came to be so pervasive in the diet that Columbus physician John Wilson Jr. observed, “Hog’s lard is the very oil that moves the machinery of life.”

European settlers came to prefer corn to other grains like rye and wheat. Corn was far easier to cultivate, harvest, and, most important, transform into meal for bread. “Slow moving and ill-matched millstones, that could grind corn into an acceptable meal, only stirred wheat into a glutinous mess,” Joe Gray Taylor writes in Eating, Drinking, and Visiting in the Old South. Until the early 1900s wheat flour was far too expensive to be used on a regular basis by most Georgians.

Though numerous other foodstuffs like peppers, peanuts, and black-eyed peas were introduced in ensuing years, the bedrock components of what would become the Georgia diet were in place at an early date: pork and corn. Even that fabled Georgia dish, fried chicken, owed a good portion of its popularity to the easy availability of a frying medium, namely lard.

African American Influence

Many of the dishes that we regard as distinctly Georgian owe their origins to European recipes and techniques—everything from hog’s headcheese to chess pie. But the introduction of enslaved Africans may have most thoroughly transformed the diet.

African Americans reinterpreted European cookery and Native American ingredients, applying African-inspired techniques and constructions. In the kitchen, African American cooks slipped in a pepper pod here, an okra pod there. Indeed, some foodstuffs we now recognize as elemental to the Georgia diet owe their presence to the slave trade. Peanuts, though native to South America, probably arrived in the South by way of slave ships, on which they were valued as hardy provisions. Okra is an African plant, as are benne (also known as sesame) and watermelon.

Georgians of African descent cooked in deep oil as they had done in Africa. They mastered the use of the sweet potato, the available tuber closest in appearance to the fibrous yams of Africa. Historian Eugene Genovese characterizes this general tendency as an example of “the culinary despotism of the [slave] quarters over the big house.”

Geographic Subregions

Geography has also been an important factor in the foodways of Georgia. The exception to the dominance of corn was coastal Georgia, where on the marshlands rice was cultivated through enslaved labor. People in this region ate rice waffles and various other rice-based breads, in addition to composed rice dishes like pilaus. Seafood was available in abundance, and the prevalence of oyster stews and deviled crab dishes reflected the bounty of the waters.

In the loamy soil of south Georgia, peanuts and pecans thrived. Though native to the region, pecan trees did not become a major crop until after the Civil War (1861-65), when planters like Nelson Tift began staking out orchards near the town of Albany. Since the 1950s Georgia has led the nation in pecan production.

Both Union and Confederate soldiers prized peanuts (which are legumes rather than true nuts) during the Civil War. They were not, however, planted often in Georgia until the early years of the twentieth century, when the boll weevil ravaged much of the cotton crop and farmers sought an alternative. Today, south Georgia—especially Early and Decatur counties—grows approximately 45 percent of the nation’s peanuts.

An even later arrival to south Georgia was the Vidalia onion. Low in sulfur and high in water content, these white onions are prized for their sweetness. The variety gets its name from the Toombs County town where farmer Mose Coleman first marketed them in the 1930s. Debate continues as to why they are so sweet, with most farmers crediting a combination of the local soil and mild winter weather.

In middle Georgia peaches have long been savored. “Even though the fruit originated in Persia and was brought to the New World by the Spaniards,” Joe Gray Taylor writes, “the first settlers in the Carolinas and Georgia found peaches under cultivation by the Indians.” In the 1870s Macon County farmer Samuel Rumph developed a hybrid peach—the Elberta—that flourished along the fall line. The variety, which did not bruise easily and thus shipped well, spurred Georgia peach production, and by the early 1900s Georgia was the leading peach grower in the nation.

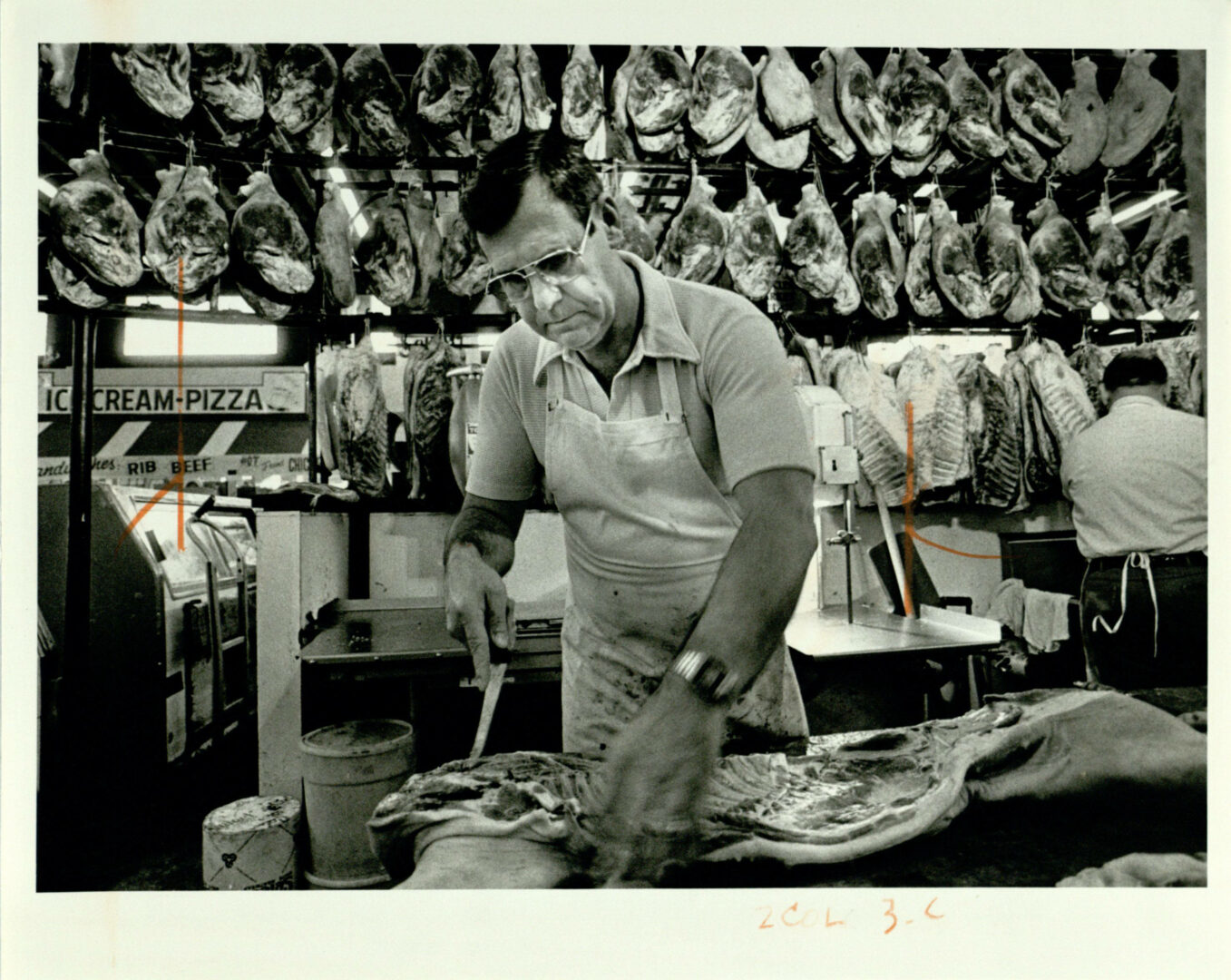

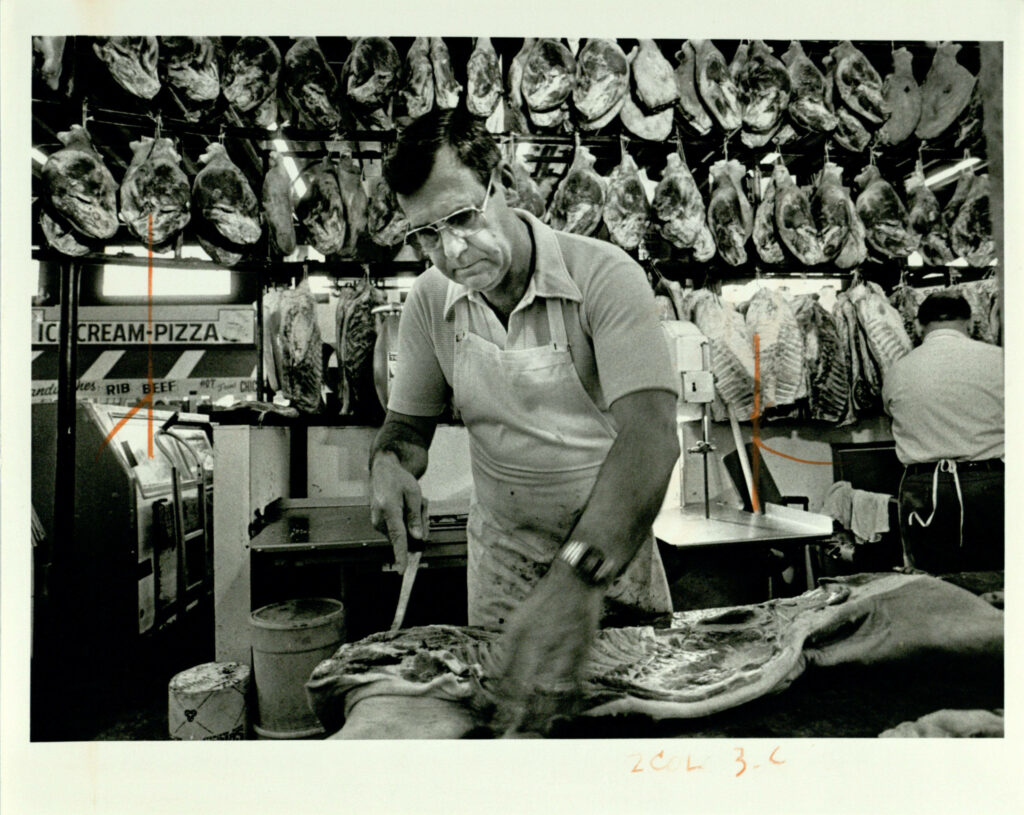

The climate of north Georgia, where cold weather comes earlier and lasts longer, has been favored for the curing of hams and other pork products. To prevent spoilage, hog killings would take place after the first frost when cold weather set in for good. The hills and valleys of the mountains were also inhabited by moonshiners, who employed techniques of their Scots-Irish forefathers to make whiskey from corn, out of sight of federal revenue agents. Owing to the apple crop centered around Ellijay, apple brandy was also popular.

The Effects of Privation

Though Georgia boasts a long growing season for vegetables and a wealth of game and fish, the state has not been immune to economic downturn. The ravages of the Civil War took their toll, as reflected in the pages of the Confederate Receipt Book, originally published in 1863, wherein instructions are given for preserving meat without salt and making ersatz coffee from acorn shells.

The Great Depression was also devastating, though in 1931 it did engender a lighthearted debate between the editors of the Atlanta Constitution and Huey P. Long, U.S. senator-elect of Louisiana, over the proper consumption of two frugal foods: pot likker (the soupy leavings from the bottom of a pot of greens) and cornbread. Long was a dunker of cornbread. The Constitution advocated crumbling, and the debate raged for more than three weeks in February and March of that year.

Modern Foodways

Such Georgia food and beverage companies as the Coca-Cola Company of Atlanta, RC Cola and Tom’s Peanuts (later Tom’s Foods) of Columbus, and the W. B. Roddenbery Company of Cairo (maker of various cane syrup and peanut products) came to prominence in the twentieth century, selling their goods in the international marketplace. Concurrently, the movement of Georgians from farms to cities and suburbs spurred an increased reliance upon prepackaged foods and a spike in the number and quality of restaurants.

In 1916 Greek immigrant James Mallis opened a hot dog stand in Macon called Nu-Way Weiners. Fresh Air Barbecue opened in 1929 as a roadside stand in the community of Flovilla, in Butts County. In 1943 Mrs. Wilkes took over the reins of a boarding house in Savannah, serving Georgia standards to railroad men. In the 1950s Atlanta’s “Deacon” Lydell Burton opened Burton’s Grill, serving fried chicken, collard greens, and hoecakes, a modern-day replication of the traditional midday groaning board.

Fads have also affected Georgia foodways. The late 1960s signaled the national debut of the term soul food, arguably a politicized renaming of the foods long savored by Black southerners.The term was in vogue at the same time as soul music and other celebrations of lack southern life. By the early 1970s soul food began moving upscale as restaurants like Atlanta’s Soul On Top O’ Peachtree opened downtown on the thirtieth floor of the Bank of Georgia Building. In 1976 the United States elected a farmer named Jimmy Carter from the south Georgia town of Plains as president, and the nation was soon smitten by the foods of his home state, especially peanuts and grits.

Video by Darby Carl Sanders, New Georgia Encyclopedia

During the later years of the twentieth century, a growing national fascination with regional foods found a foothold in the South, as cookbooks were published touting “new southern cooking.” Restaurants serving updated takes on traditional recipes (fried green tomatoes topped with crab and pecan-crusted catfish, for example) opened in Atlanta and elsewhere. Ironically, farmers, responding to this trend, began planting older varieties of vegetables and fruits that might have been recognizable to a Georgian of 100 years ago.

Georgia Food Authors and Cooks of Note

Georgians did not relegate their knowledge of food to the kitchen. A number of acclaimed Georgia cooks also published food books.

Mrs. S. R. Dull, a native of Laurens County, was the longtime editor of the home economics page of the Atlanta Journal. Her 1928 book of collected recipes, Southern Cooking, was encyclopedic in scope and long regarded as a primer by southern homemakers.

Harriet Ross Colquitt was the author of The Savannah Cookbook, a more colorful and quirky collection of recipes, chock full of such coastal standards as mulatto rice (a composed rice dish with tomatoes) and Chatham Artillery Punch (a kitchen-sink conglomeration of, among other liquors, brandy, gin, rye, and rum). Published in 1933, the book boasts a foreword by poet Ogden Nash wherein he proclaims, “Everybody has the right to think whose food is the most gorgeous / And I nominate Georgia’s.”

Eliot Wigginton was, in the early 1970s, the first editor of Foxfire, a cultural journal created by his students at Rabun Gap–Nacoochee School in northeast Georgia. The student-collected remembrances of vegetable canning, hog killing, and apple butter–making soon proved to be very popular, spurring a best-selling series of books.

Nathalie Dupree of Social Circle was arguably one of the catalysts for the rediscovery of southern cookery by modern Georgians. Her 1986 public television show, New Southern Cooking, and cookbook of the same name featured both the old (poke sallet) and the new (grits with yogurt and herbs).

There are also many accomplished Georgia cooks who have earned their reputation not by the written word but by turning out platter after platter of good southern food. Their names should be remembered as well: Nita Dixon, the famed Lowcountry cook at Nita’s Place in Savannah; Charlie Pierce, the barbecue pitmaster at Vandy’s in Statesboro; Wilbur Mitcham, the chicken cook at Len Berg’s in Macon; Robert and James Paschal, proprietors of Paschal’s in Atlanta; Mary Margaret Lupo, the longtime owner of Mary Mac’s, also of Atlanta; and the Dillard family of the 1915-vintage Dillard House in Rabun County.