The Savannah Tribune, a weekly newspaper covering news and issues related to Savannah’s African American community, was founded in 1875. With the exception of two hiatuses, from 1878 to 1886, and from 1960 to 1973, the paper has operated continuously. As of 2008 the Tribune circulated to approximately 10,000 readers under the direction of Shirley B. James, the paper’s owner, publisher, and editor.

Early Years

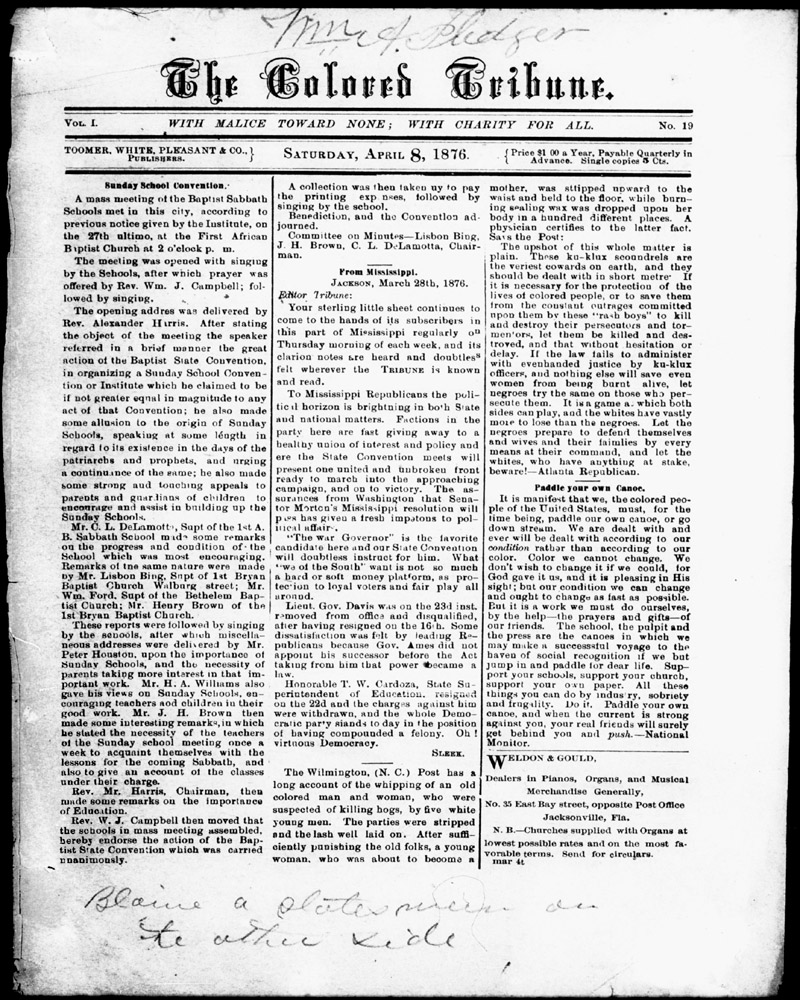

The years between U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 Emancipation Proclamation, issued during the Civil War (1861-65), and the postwar Reconstruction era ushered in a brief period of opportunity for southern African Americans, particularly in the political arena. During those years a Black press emerged in the South, but many of these publications folded with the official end of Reconstruction in 1871. The Savannah Tribune, originally called the Colored Tribune, published its first edition in 1875, a perilous time for African Americans in the South. White resistance to Black progress percolated during Reconstruction and eventually resulted in the segregation policies of the 1890s and, ultimately, the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915.

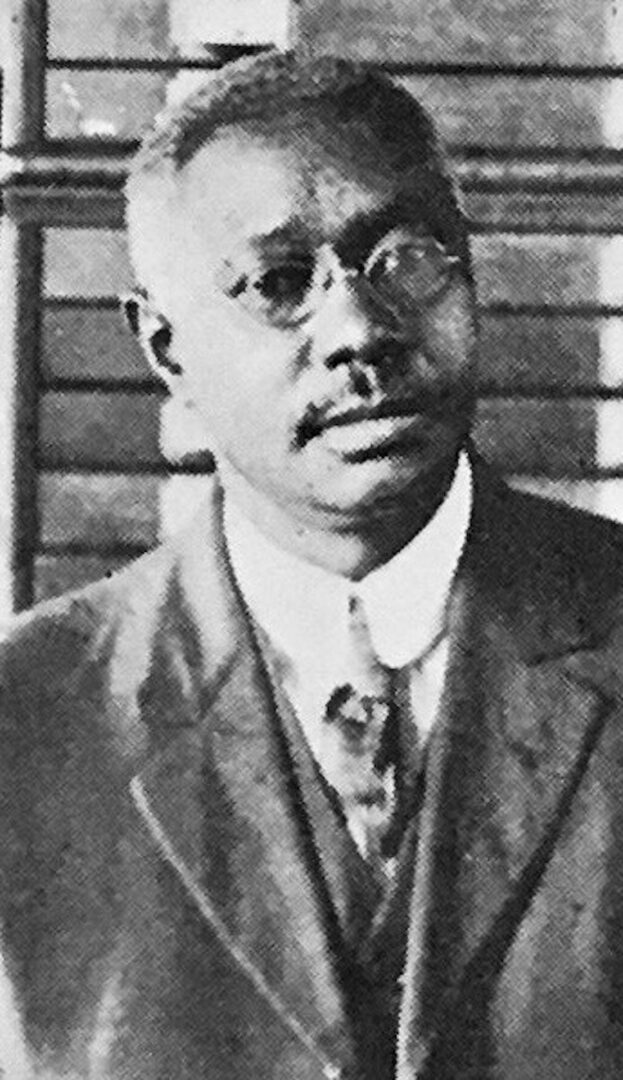

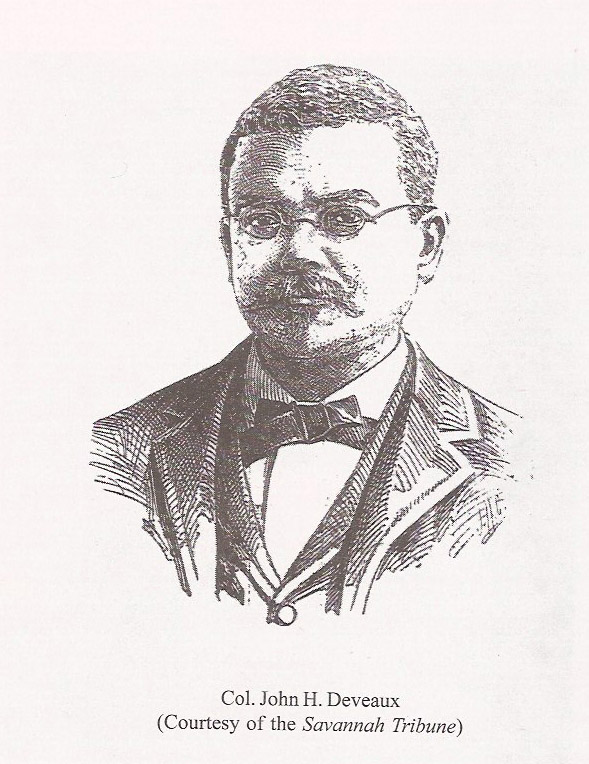

Despite such unfavorable odds, Savannah native John H. Deveaux established the Colored Tribune with the stated purpose in his first issue of defending “the rights of the colored people, and their elevation to the highest plane of citizenship.” He changed the newspaper’s name to the Savannah Tribune in 1876. Deveaux, born in 1848 to a free Black family, was a prominent businessman in Savannah and had sufficient personal resources to mount the enterprise. The newspaper survived until 1878, when it closed because the printers in the city, all white, refused to produce it. Deveaux reopened the paper in 1886 and served as editor until 1889, when he was appointed as the collector of customs and moved to Brunswick. Solomon “Sol” C. Johnson then assumed the editorship and later purchased the paper upon Deveaux’s death in 1909.

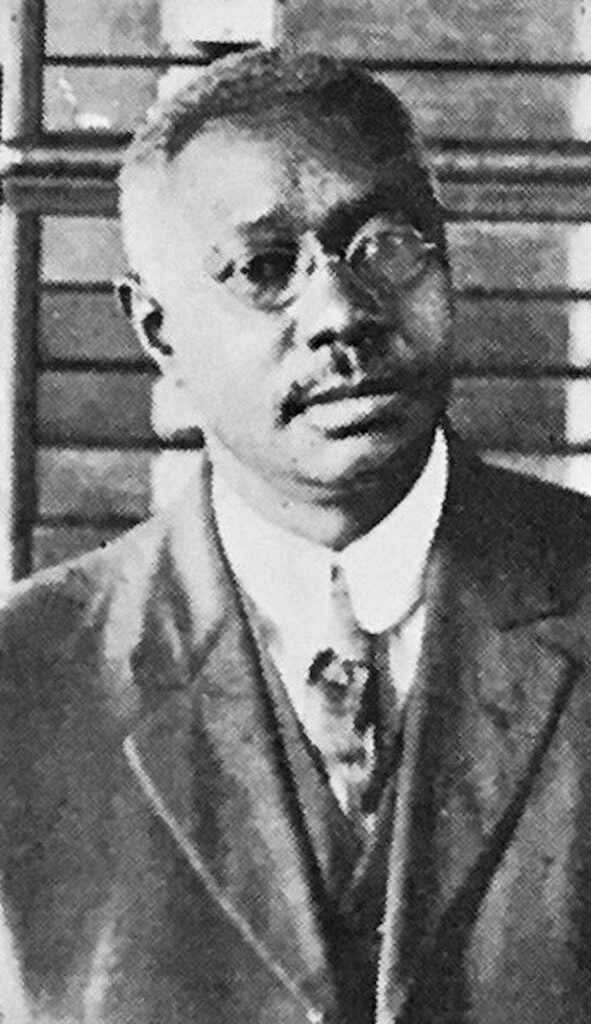

Johnson, born in 1868, had lived in Savannah since childhood and managed other thriving business interests as well. But the success of the paper, according to historian Jeffrey Alan Turner, cannot be explained merely in economic terms. As he points out, “One does not have to look hard to find Black editors in the South who spoke out too strongly against white society. . . . Deveaux and Johnson must have had a sense for when they could criticize the system—as they often did—and when they needed to be cautious.”

During Johnson’s editorship, the Tribune served as south Georgia and north Florida’s only medium for news about the injustices of the Jim Crow era. The paper encouraged its readership to resist segregation, particularly in Savannah’s streetcar system, and also covered such contentious issues as the Atlanta race massacre of 1906, lynchings around Georgia, the convict lease system, and the lack of educational opportunities for Black children in Savannah.

By the 1920s the newspaper had moved from a generally conciliatory stance toward whites to a more strident voice for racial equality. It also served as a forum for the Black literati. James Weldon Johnson, a prominent Harlem Renaissance writer, served as a correspondent for the Tribune in the 1920s, during his tenure as executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Sol Johnson ran the publication until 1954, when he was succeeded by Willa Johnson, who edited the paper until 1960.

Decline and Reemergence

The Tribune faced significant competition in 1928 with the establishment of the Atlanta World (later the Atlanta Daily World), which became the preeminent Black newspaper in the state; by the 1930s the Daily World had gained a national readership. Nevertheless, the Tribune continued publication until 1960, when it succumbed to a national trend in the Black media by closing its doors. Industry analysts attribute this decline of the Black press in part to a belief among readers that, because racial parity was at hand, Black publications were no longer relevant.

After a thirteen-year hiatus Robert E. James, a banker, reestablished the Tribune in 1973. He served as owner and publisher until 1983, when his wife, Shirley B. James, an educator and community leader, became the publisher and sole owner. Under their editorship, local and national news that is primarily of interest to African Americans dominates the front pages of the Tribune, along with articles about local African American community events. The Tribune continues to champion African American causes and promote a positive image of the African American community.

During the mid- to late-1990s, the publication departed from its typical coverage to report on an ongoing police scandal in Savannah, which led to the prosecution of eleven Black law enforcement officers for colluding with drug distribution rings.

Like many of its peers, the Tribune is a small, privately owned business, and its losses or profits are not made public. The paper’s revenues come primarily from advertising by local and national retailers, banks, grocers, educational institutions, and government entities. Even as its primary competitor, the conservative Savannah Morning News, has diversified its newsroom and shown an increased willingness to cover issues of concern to a Black audience, the editors and publishers of the Tribune still claim an important niche in the Savannah community.

In January 2006 an electrical fire scathed the inside of the newspaper’s office. The community rallied around the Tribune in the wake of the fire, and Savannah State University, a historically Black university, offered Tribune staff members the use of computers in its journalism department. During the week of the fire, the Tribune purchased new computers and relocated to a building owned by Robert James at 1805 Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in Savannah, where the newspaper continues its proud tradition of never missing a publication date since being reestablished by the James family.