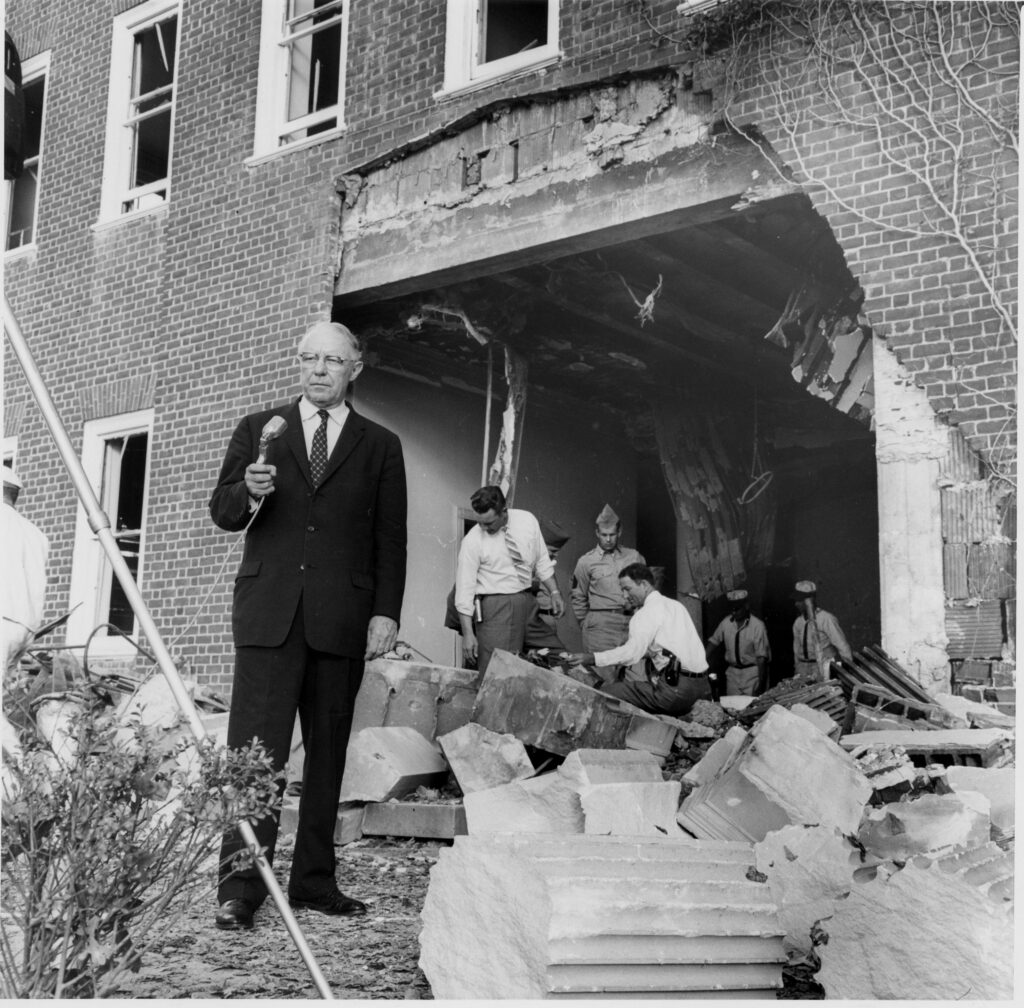

In the early hours of October 12, 1958, fifty sticks of dynamite exploded in a recessed entranceway at the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, Atlanta’s oldest and most prominent synagogue, also known as “the Temple.” The sanctuary was largely unharmed, but other parts of the building were severely damaged. No people were hurt or killed, but the blast shook the city’s confidence and rattled its composure, causing many to reappraise, however briefly, Atlanta’s reputation as “the City Too Busy to Hate.”

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

In the 1950s Atlanta was a business-friendly boomtown full of tireless boosters and eager to become one of a handful of the nation’s elite cities. Members of its political and business establishments governed the city pragmatically and were protective of the city’s reputation as an oasis of decency, if not liberalism, in an otherwise dim region. Local leaders feared that this carefully cultivated image was in jeopardy when the Temple was bombed, and the incident continued to make news until the following January, when one suspected bomber, George Bright, was tried and acquitted. Charges against the other suspects were dropped.

Background

Though small in number, Jews had been present in Atlanta since its founding in the mid-nineteenth century and were well represented among the city’s merchant and professional classes. The roughly 1,000 Jews who belonged to the Temple at the time of its bombing were similarly situated, and numerous members enjoyed prominence in a variety of fields. Their professional success notwithstanding, however, Atlanta’s Jews were frequently denied membership in the city’s exclusive social clubs and often encountered discrimination in civic affairs.

Photograph by David

In order to overcome the suspicions of their gentile neighbors, Temple congregants under the leadership of Rabbi David Marx, who served the Temple congregation between 1895 and 1946, took care to minimize the cultural divide separating Atlanta’s Jewish and Christian communities. Conflicts were avoided whenever possible, and efforts were undertaken to foster good relations with mainstream Christian society. Marx’s conciliatory instincts contrasted with the notorious lynching of Leo Frank in 1915, which revealed a virulent strain of anti-Semitism in Georgia and produced a profound sense of insecurity in the city’s Jewish population.

Marx’s successor, Jacob Rothschild, recoiled at Marx’s reforms. Though he too sought to maintain good relations with his Christian counterparts, Rothschild reinstated traditions that his predecessor had allowed to lapse, and encouraged his congregants to observe religious strictures that he deemed essential to Jewish identity. However, it was Rothschild’s support of racial integration, rather than his observance of religious custom, that earned him most renown. Begining on Yom Kippur (one of the most important Jewish religious holidays, which falls in September or October) in 1947, Rothschild used his pulpit and position to critique segregation in the region. While this stance won admiration from some quarters, it aroused contempt from others and likely made the Temple a target of extremist violence.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which called for the desegregation of public schools, the South was transformed into a tinderbox of racial tension. Southern politicians vowed to defend the region’s Jim Crow segregation and urged their constituents to defy federal authorities. As massive resistance to Brown gained traction, staunch segregationists sometimes responded to the ruling violently, targeting churches and synagogues that promoted integration. The Temple in Atlanta was the fourth southern synagogue to be bombed in little more than a year. Only days later, another synagogue was bombed, this time in Peoria, Illinois.

Because of recent events in Atlanta’s history, the Temple was perhaps more vulnerable than most progressive institutions in the region. In 1957 Martin Luther King Jr. returned to Atlanta to establish the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which soon became a leading organization in the civil rights movement. Meanwhile, many whites felt threatened by a pending lawsuit to desegregate the city’s public transportation system—the U.S. Supreme Court had already ordered the city to desegregate its public golf courses in 1955. What made the Temple a likely target of attack, however, was Rothschild’s activism. In response to the 1957 Little Rock Central High School integration crisis—during which nine Black students attempted to integrate the school, against the efforts of Arkansas governor Orval Faubus as well as an angry white mob—Rothschild coauthored what became known as the Ministers’ Manifesto. The document called for moderation, communication between the races, racial amity, and most important, obedience to the law. Although he did not sign the manifesto because he believed it would be most effective if couched in unambiguously Christ-focused language, Rothschild praised the document in his sermons and in a follow-up editorial for the Atlanta Sunday Journal-Constitution. Five months before the bombing, the rabbi defended his position in what must have later seemed like prophetic terms. “We must resolve not to surrender to violence,” he told his congregation, “or submit to intimidation.”

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Reaction

Although initial estimates suggested that the Temple had suffered more than $200,000 in damage, later estimates placed the figure closer to $100,000. Fortunately, the building was vacant at the time of the blast, and the Temple’s historic sanctuary remained unharmed. Still, the damage was immense. An entire wall was blown apart by the blast, offices were destroyed, a stairwell was mangled and unhinged, and shards of stained glass littered the Temple’s grounds.

Worse than the physical damage to the building was the anxiety suffered by local Jews. Because memories of the Leo Frank lynching and the cultural isolation it had engendered still lingered within that community, many worried that their contemporaries in mid-century Atlanta might react to their plight with indifference or worse.

Such fears were quickly dispelled, however. Upon receiving news of the blast, Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield made haste to the Temple, where he issued a statement condemning the bombers and political demagogues that he believed shared the blame. Hartsfield said, “Whether they like it or not, every political rabble-rouser is the godfather of these cross burners and dynamiters who sneak about in the dark and give a bad name to the South. It is high time the decent people of the South rise and take charge.” Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill, whose Pulitzer Prize–winning editorials on the event were later compiled in the volume A Church, a School (1959), echoed the mayor’s sentiments in his column the next morning, stating: “This . . . is a harvest of defiance of the courts and the encouragement of citizens to defy law on the part of many Southern politicians.” U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower also condemned the bombing and pledged the support of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in apprehending the perpetrators.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Local institutions and ordinary citizens throughout the city clamored to lend their support. After Mayor Hartsfield pledged $1,000 on behalf of the city for information leading to the arrest of the bombers, others followed suit, and more than $20,000 was soon pledged. Temporary offices for the Temple staff were quickly installed at the nearby Atlanta Jewish Community Center, and the Atlanta School Board offered its facilities for use on weekends. By Monday morning the Temple’s front lawn bulletin advertised the title of Rabbi Rothschild’s Friday evening sermon: “And None Shall Make Them Afraid.”

The Trial

In one of the most extensive investigations in state history, more than seventy-five city detectives and numerous FBI and Georgia Bureau of Investigation agents fanned out across the city to search for clues to the bombers’ identities. Within days, five men were placed under arrest and jailed. The suspects all belonged to anti-Semitic hate groups, including the National States Rights Party and the Knights of White Camilla. Although each man was believed to be connected to the bombing, only one, George Bright, stood trial.

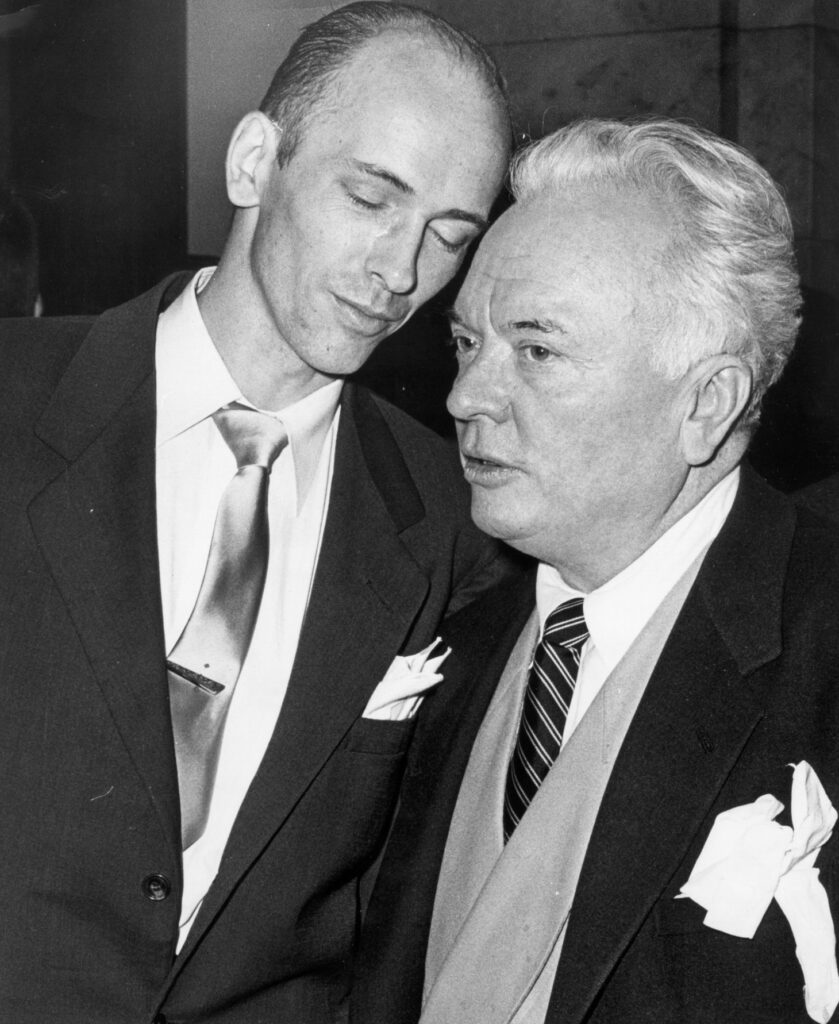

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

After uncovering a handwritten note in Bright’s home threatening Rabbi Rothschild, prosecutors decided to pursue the thirty-four-year-old engineer first, with the hope that a guilty verdict in his trial would lead to more convictions. A native of New York, Bright had spent his adult life in Atlanta. In 1946, at the age of twenty-two, he joined the Columbians, a neo-Nazi fascist organization headquartered in the city. Thereafter, he became affiliated with other fringe groups, maintained communication with a network of like-minded extremists, and devoted his spare time to the study of anti-Semitic texts and other writings that warned of the dangers posed by mixed race marriages, integration, and communism. In May 1958 Bright appeared in the audience at a speech given by Rothschild and briefly heckled the rabbi before being escorted outside the building by authorities. Two months later he was among several men arrested for carrying anti-Semitic placards outside the offices of the Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution.

Bright’s first trial began on December 1, less than two months after the bombing, and ended ten days later in a mistrial. The jurors were divided 9-3. It later became known that even the jurors favoring acquittal believed Bright to be guilty, but they felt unable to support a conviction carrying a possible death sentence on the circumstantial evidence presented.

For his second trial, Bright retained Reuben Garland, a shrewd attorney known for his garish attire and flamboyant courtroom performances. Although his outlandish tactics earned him a jail sentence for contempt of court, Garland secured an acquittal for his client. Charges against the remaining four defendants were later dropped.

Members of Atlanta’s Jewish community were distressed by the outcome. In his sermons, however, Rothschild encouraged his congregation to look beyond the verdict, reminding them that “the process was sound—and it is in the process that our freedom and security rest.” Whereas two generations earlier the Frank case had revealed lawlessness and rampant anti-Semitism, the Temple bombing did not. Because the incident elicited universal condemnation from all quarters of the city, Rothschild concluded that the bombing did not represent a victory for anti-Semitism, but instead a rejection of it.

The Temple bombing held significance for those outside Atlanta’s Jewish community as well. Atlanta avoided the bloodshed and rancor that marked the experiences of its regional peers during the tumultuous years of the civil rights movement. The city desegregated its schools without incident, peacefully integrated public facilities, and even hosted an integrated gala dinner, cochaired by Rothschild, to honor Martin Luther King Jr. for receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. Such reforms may not have been possible were it not for the moderate consensus that emerged in the bombing’s wake.