Milledgeville is the seat of Baldwin County in central Georgia. It served as the fourth capital of Georgia (1804-68) and was the seat of the state government throughout the Civil War (1861-65). According to the 2020 U.S. census, its population was 17,070.

Founding and Early Years

In 1803 an act of the Georgia legislature called for the establishment and survey of a town to be named in honor of the current governor, John Milledge. The land immediately west of the Oconee River had just been opened up by the Treaty of Fort Wilkinson (1802), in which the Creek Indians, hard pressed by debts to white traders, agreed to cede part of their ancient land. The restless white population of Georgia was pressing west and south in search of new farmland, and the town of Milledgeville was carved out of the Oconee wilderness to help accommodate their needs. The area was surveyed, and a town plat of 500 acres was divided into 84 four-acre squares. The survey also included four public squares of twenty acres each. In December 1804 Milledgeville was declared by the legislature to be the new capital of Georgia. The new town, modeled after Savannah and Washington, D.C., was located on the edge of the frontier, where the Upper Coastal Plain merges into the Piedmont.

In 1807 fifteen wagons, escorted by troops, left Louisville, the former capital, carrying the treasury and public records of the state. The new statehouse, though unfinished, was able to accommodate the legislators. Over the next thirty years the building was enlarged with a north and south wing. Its pointed arched windows and battlements marked it as America’s first public building in the Gothic revival style. Governor Jared Irwin soon moved into a handsome two-story frame structure known as Government House, on the corner of Clarke and Greene streets. The new capital was a rather crude frontier community with simple clapboard houses, a multitude of inns and taverns, law offices, bordellos, and hostelries. The town attracted several blacksmiths, whitesmiths, apothecaries, dry-goods merchants, and even booksellers. Travelers to the town were generally unimpressed, noting the ill-kept and overcrowded inns, the gambling, the dueling, and the bitter political feuds.

Life in the Antebellum Capital

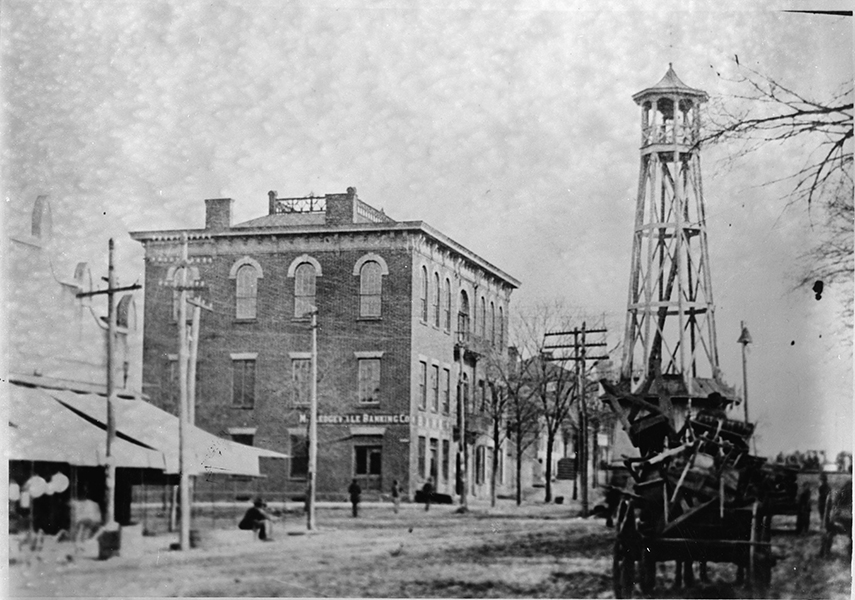

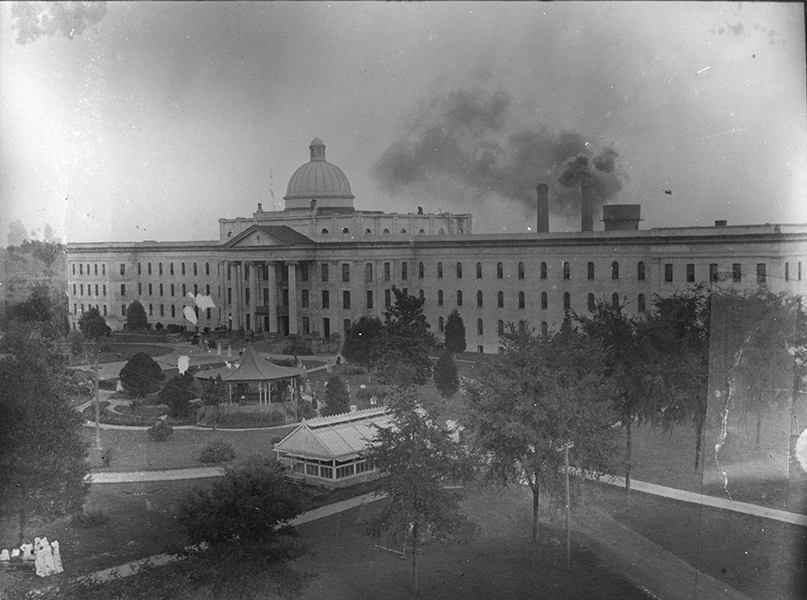

After 1815 Milledgeville became increasingly prosperous and more respectable. Wealth and power gravitated toward the capital, and the surrounding countryside was caught up in the middle of a cotton boom. Streets were lined with cotton bales waiting to be shipped downriver to Darien. Such skilled architects as John Marlor and Daniel Pratt were designing elegant houses; colossal porticos, cantilevered balconies, pediments adorned with sunbursts, and fanlighted doorways all proclaimed the Milledgeville Federal style of architecture. The major churches built fine new houses of worship on Statehouse Square. The completion in 1817 of the Georgia Penitentiary heralded a new era of penal reform. Public-spirited citizens like Tomlinson Fort (mayor of Milledgeville, 1847-48) promoted better newspapers, learning academies, and banks. In 1837-42 the Georgia Lunatic Asylum (later the Central State Hospital) was developed. Oglethorpe University, where the poet Sidney Lanier was educated, opened its doors in 1838. (The college, forced to close in 1862, was rechartered in 1913, with its campus in Atlanta.) The cotton boom also significantly increased the enslaved population; by 1828 the town claimed 1,599 inhabitants: 789 free whites, 27 free Blacks, and 783 enslaved African American. The town market, where slave auctions were held, stood next to the Presbyterian church on Capital Square. Black carpenters, masons, and laborers constructed most of the handsome antebellum structures in Milledgeville.

Two events epitomized Milledgeville’s status as the political and social center of Georgia in these years. The first was the visit to the capital in 1825 by the Revolutionary War (1775-83) hero the Marquis de Lafayette. The receptions, barbecue, formal dinner, and grand ball for this veteran apostle of liberty seemed to mark Milledgeville’s coming of age. The second event was the construction (1836-38/39) of the Governor’s Mansion, one of the most important examples of Greek revival architecture in America.

The Civil War and Its Aftermath

On January 19, 1861, Georgia convention delegates passed the Ordinance of Secession, and the “Republic of Georgia” joined the Confederate States of America, to the accompaniment of wild celebration, bonfires, and illuminations on Milledgeville’s Statehouse Square. Nearly four years later, on a bitterly cold November day, Union general William T. Sherman and 30,000 Union troops marched into Milledgeville. When they left a couple of days later, the statehouse had been ransacked; the state arsenal and powder magazine had been destroyed; the penitentiary, the central depot, and the Oconee bridge were burned; and the surrounding countryside was devastated. In 1868, during Reconstruction, the capital was moved to Atlanta—a city emerging as the symbol of the New South as surely as Milledgeville symbolized the Old South.

Milledgeville spent the remaining years of the nineteenth century trying to survive the loss of the capital. Through the energetic efforts of local leaders, the Middle Georgia Military and Agricultural College (later Georgia Military College) was established in 1879 on Statehouse Square. Where the crumbling remains of the old penitentiary stood, Georgia Normal and Industrial College (later Georgia College and State University) was founded in 1889. In part because of these institutions, as well as Central State Hospital, Milledgeville remained a less provincial town than many of its neighbors.

The Twentieth Century

As the old capital moved into the twentieth century, it produced a number of people who would attain national prominence. Among these were the distinguished chemist Charles Herty; epidemiologist Joseph Hill White; Woodrow Wilson’s treasury secretary, William Gibbs McAdoo; and Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, a noted historian of the South. The most famous twentieth-century Milledgevillians, however, form an unusual trio. In 1910 eighteen-year-old Oliver Hardy, of Laurel and Hardy fame, moved to Milledgeville, where his mother managed the stately old Baldwin Hotel, and stayed for three years. U.S. Congressman Carl Vinson represented his hometown of Milledgeville and central Georgia for fifty years (1914-65). The writer Flannery O’Connor came as a young girl with her family to Milledgeville from Savannah. O’Connor, a 1945 graduate of Georgia State College for Women, did much of her best writing in Milledgeville at her family’s farm, Andalusia, which offers public tours. Her critically acclaimed short stories and novels have secured her reputation as a major American writer.

In the 1950s the Georgia Power Company completed a dam at Furman Shoals, about five miles north of town, creating a huge reservoir called Lake Sinclair. The lake community became an increasingly important part of the town’s social and economic identity. In the 1980s and 1990s Milledgeville began to capitalize on its heritage by revitalizing the downtown and historic district. Another attraction, Lockerly Arboretum, offers tours of the facility’s botanical gardens as well as educational programs and the Lockerly Heritage Festival each fall.

A satellite campus of Central Georgia Technical College is located in Milledgeville.