Confederate veteran organizations were formed to alleviate and address many of the challenges facing former soldiers and their communities in the aftermath of the Civil War (1861-65). The objectives of these organizations included burying and commemorating dead soldiers; caring for cemeteries; providing aid to widows, orphans, and indigent veterans; and preserving the Confederate interpretation of the war’s history (often referred to as Lost Cause ideology).

These organizations later served an important social function by helping veterans maintain ties to those with whom they had served, both through reunions and through such magazines as Confederate Veteran, which was founded in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1893 and published until 1932.

Early Organizations

Founded in 1865, the Oglethorpe Light Infantry Association in Savannah was one of Georgia’s earliest military veteran organizations. Organized by “company,” “regiment,” or “brigade,” military-type organizations served as one of the best ways to reunite men who had served together in the war.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

A number of local organizations were established in the late 1870s and throughout the 1880s. In 1878 Augusta-area veterans formed the Confederate Survivors’ Association (CSA), under the leadership of Stewart County native Clement Evans. Like many of the other early veteran groups, the CSA sought to encourage friendship among veterans, to protect memories of the past, to promote the practice of “manly virtues,” and to provide for sick and indigent veterans. Despite these broadly defined objectives, the CSA functioned primarily as a memorial society in its early years.

The Fulton County Confederate Veteran’s Association formed on April 20, 1886, at the Fulton County courthouse in Atlanta. Originally consisting of 182 members, the organization was led by a mission similar to that of the Augusta association and in addition sought to compile a “true” history of the war as its members had known it. The association’s earliest members included such “first citizens” of Georgia as Samuel Inman, reputedly one of the richest men in the state, and W. Lowndes Calhoun, a former mayor of Atlanta. Though not a veteran himself, Henry W. Grady, the acclaimed journalist and managing editor of the Atlanta Constitution, held an honorary membership.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In addition to his affiliation with the Fulton County Confederate Veteran’s Association, Grady was heavily involved in the early stages of developing a Confederate soldiers’ home for veterans. Grady’s sudden death in 1889 and the subsequent political controversy over the site of the home led to a decade-long struggle to secure legislative approval for the project, which had by then been embraced by other veterans’ and women’s organizations. The home finally opened in Atlanta on June 3, 1901, the birthday of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, with forty “gray hair remnants” from twenty-six Georgia counties moving in. Though the building was destroyed by fire three months later, a new home was built and opened a year later. It remained standing until 1967 and ultimately housed around 1,200 Georgia veterans over the course of its existence.

The United Confederate Veterans

By far the largest and most influential Confederate veteran organization was the United Confederate Veterans (UCV). Founded in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1889, the UCV was created for mostly social, charitable, and memorial functions. However, it also sought to unify the many separate organizations scattered across the former Confederate states into one larger regional body. The UCV conducted much of its activity through committees on history, relief, finance, and monuments, and it was organized hierarchically along military lines with a commander in chief, officers who held rank, and local associations known as “camps.”

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

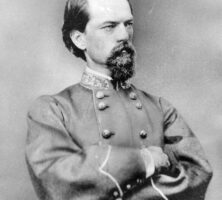

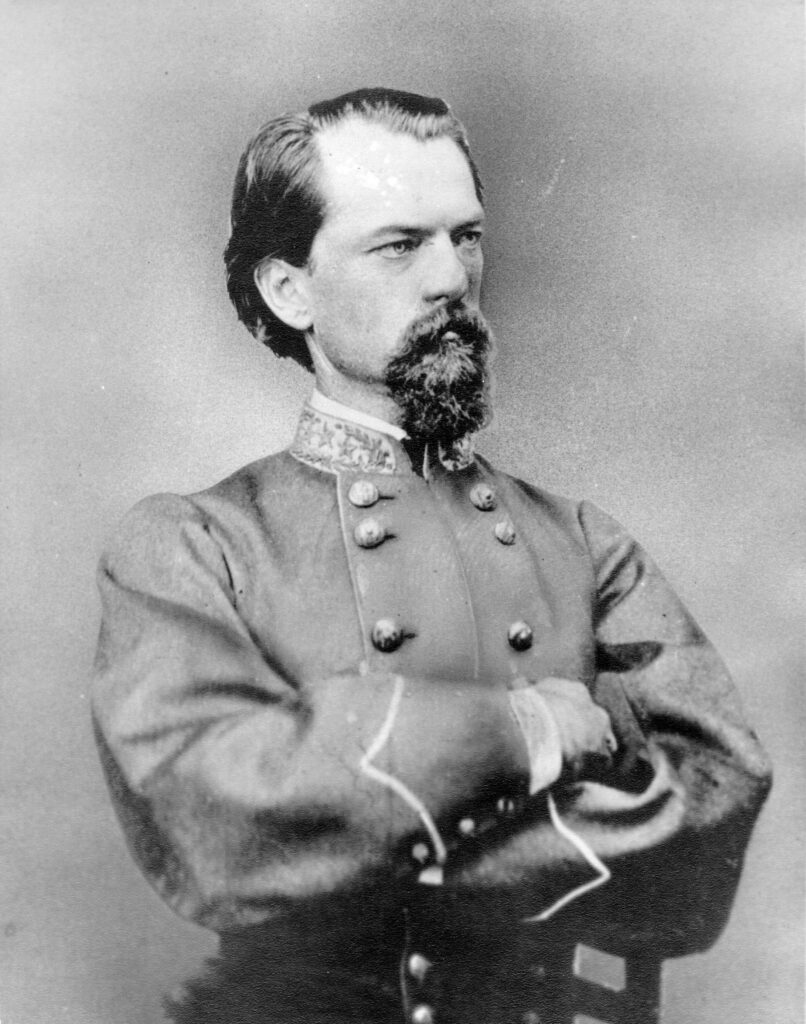

Georgia native John B. Gordon, former Confederate general and head of the Georgia Veterans’ Association, was elected the UCV’s first commander in chief. In addition to his administrative duties as commander, Gordon presided over the conventions, oversaw the formation of new member groups, and served as the spokesman for the organization. Many saw Gordon’s leadership of the UCV as representing a significant shift away from the Virginia-dominated leadership and agendas of the early postwar years. Some southerners found Gordon’s priorities too slanted toward reconciliation efforts with the North, but he remained very popular with the rank and file, and maintained his position as commander in chief until his death in 1904. Clement Evans, a UCV founder, headed the Georgia chapter for twelve years and served as commander in chief from 1908 to 1910.

Photograph by Wikimedia

Auxiliary Groups

By 1890 Georgians made up nearly 11 percent of living Confederate veterans, with only Virginians and Texans registering higher numbers, and 88 percent of Georgia counties had individual UCV “camps,” one of the highest rates in the South. Many of these camps formed auxiliary groups that included other members of veterans’ families. Katharine Du Pre Lumpkin, whose father was an early leader in Georgia’s veteran activities, describes such roles in her autobiography, The Making of a Southerner (1947): “My mother and older sister were 'Daughters of the Confederacy’; my brothers, as each grew old enough, [were] 'Sons of Confederate Veterans’; we who were the youngest [were] 'Children of the Confederacy.'”

In 1896 male descendants of veterans organized their own association independent of the UCV. The organization was originally called the United Sons of Confederate Veterans, but concern that it might be confused with the United States Colored Volunteers, which shared the acronym USCV, led its members to drop “United” to become the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV).

Reunions

The earliest veteran reunions tended to be local. Lumpkin claimed that the first regimental reunion of Confederates in the South was an 1874 gathering of Third Georgia Regiment veterans in Union Point, in Greene County. The reunion was organized by her father, who had served with that unit.

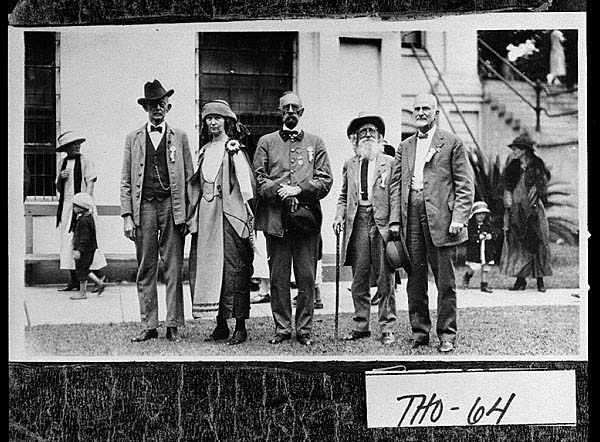

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Over the history of the UCV, annual national reunions were held in nearly thirty cities, almost all in the South. In addition, “Blue-Gray,” or combined, reunions of Confederate and Union veterans were held several times. These were encouraged by John B. Gordon and others as an effective means of demonstrating reconciliation between the North and the South. Individual states also held their own UCV division reunions, at which delegates to the national reunions were elected. While Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Richmond, Virginia, hosted the greatest number of national reunions, Atlanta hosted them in 1898, 1919, and 1941, with an additional Blue-Gray reunion there in 1900. Macon, the only other city in Georgia to host a national reunion, held the 1912 event.

The reunions came to have such a strong religious tone, opening with prayers and usually including a memorial service for the deceased, that the Chaplains’ Association was made an official auxiliary group at the 1898 meeting in Atlanta, which had more than 60,000 in attendance.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Attendance at Confederate reunions began to diminish by the early twentieth century. The last national UCV reunion was held in 1951 in Norfolk, Virginia. At the time, only twelve Confederate veterans were known to be living. Three attended the reunion, including William Joshua Bush from Fitzgerald.

Historical Mission

One particular area in which the UCV took great interest was the remembrance and interpretation of the war. Members of the UCV’s history committee sought to recognize those books that they believed treated the Confederacy fairly and to condemn those that did not. In 1892, for example, the UCV approved only nine texts, all written by southerners, as appropriate for use in southern classrooms. The UCV denounced history books that depicted Confederates as rebels or traitors and lobbied textbook companies to use the phrase “Civil War between the states” instead of “war of rebellion.”

Equally as strong a priority was the collection and preservation of soldiers’ own memories of their war experience. The Southern Historical Society (SHS) was founded in New Orleans in 1869 primarily as a means of collecting firsthand testimonials by former Confederates. Even earlier, Charles C. Jones Jr. of Savannah began collecting Confederate service records and reminiscences of former soldiers, and he continued to do so until the 1880s. Though he never wrote a history of the Confederacy, as was his original intention, he often drew on his collection of testimonials for the frequent speeches he made to veteran groups throughout the state. His efforts prompted many veterans to write book-length memoirs and reminiscences of their war years.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.