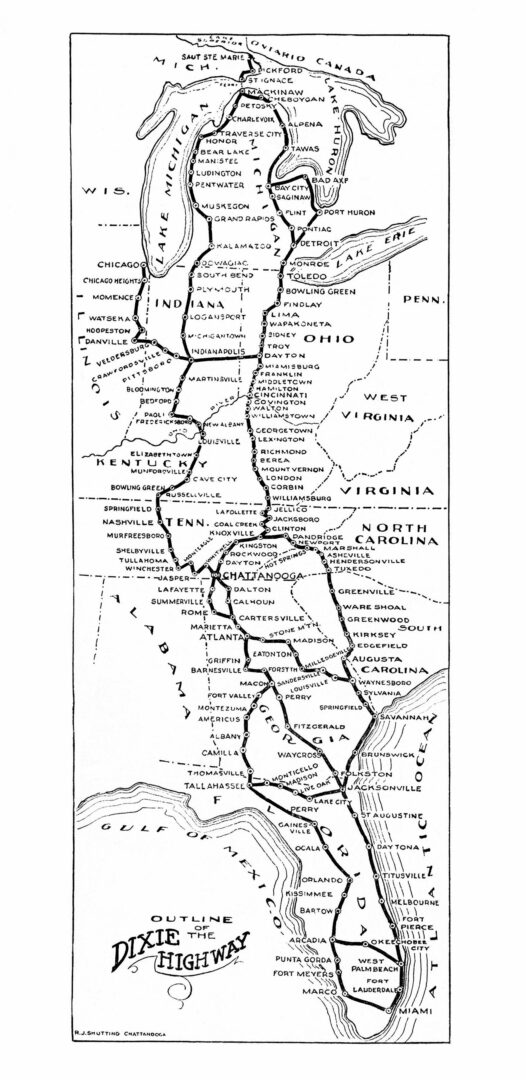

The Dixie Highway, a network of roads connecting Canada to Florida in the early decades of the twentieth century, was an ambitious undertaking to build the nation’s first north–south paved interstate highway. As the largest state in terms of area east of the Mississippi River, Georgia proved critical to the project’s success, mainly because the state’s size and location controlled access to Florida for anyone driving by car.

Signs marked “Dixie Highway” still exist on roadways throughout Georgia, particularly on old U.S. Highway 41. References to the Dixie Highway no longer appear on Georgia’s official state highway map, nor is it mentioned in most Georgia or U.S. history textbooks, yet this overlooked highway had a dramatic impact on Georgia and Florida before the arrival of interstate highways in the 1960s. Almost every Florida-bound tourist had to drive through Georgia—something that frequently proved impossible when rain turned Georgia’s dirt roads into mud. Even in dry weather, the Peach State’s terrible roads were a challenge—not just for tourists but also for local farmers and residents.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

Road Improvement Efforts

As late as 1915 Georgia boasted very few paved streets and no paved highways. The state’s roads were made of dirt and had evolved over almost two centuries of use by wagons and buggies.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

Since colonial days, road construction and maintenance had been a local function. By law, able-bodied men were required to perform annual road duty (or pay a commutation tax). Additionally, many convicts were assigned to work on the roads. But, in the absence of motorized road equipment and funding, there was little that men with shovels and mule-drawn scrapers could do to keep dirt roads passable year-round.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

The impetus for improved roads began in the late nineteenth century, when bicycle enthusiasts launched the Good Roads Movement and the U.S. Post Office began rural mail delivery. But the real push for improved roads came with the development of the automobile—particularly after 1908, when Henry Ford’s new assembly line made his Model-T affordable to an increasing number of Americans. Still, the automobile was of little practical use if there were no reliable roads to drive upon.

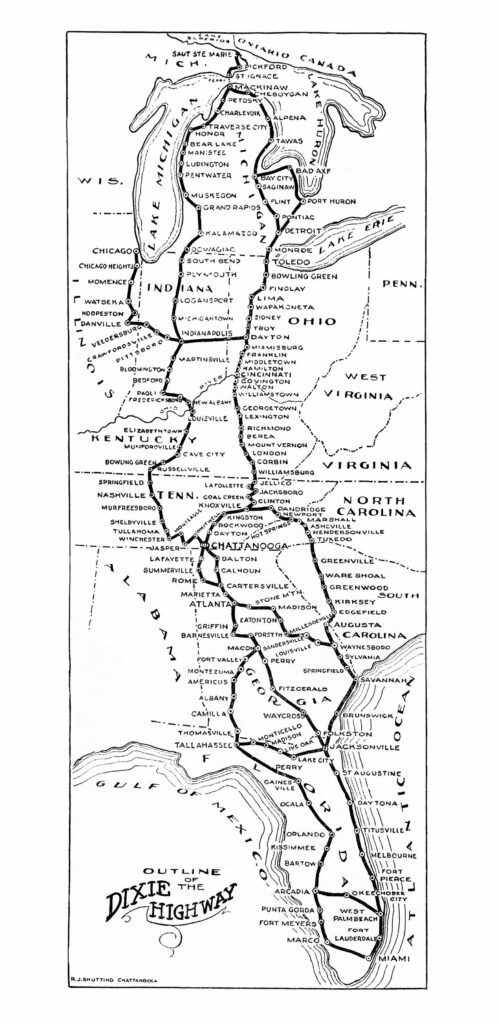

To address America’s need for improved roads, an alliance of highway supporters, auto trade associations, and others espoused a network of “national highways.” Probably the most famous of these proposed roadways was the Lincoln Highway, which would connect the east and west coasts. One of its chief supporters, an eccentric and wealthy visionary and entrepreneur named Carl Fisher, also became a champion of America’s first north-to-south interstate paved road. After purchasing much of a largely vacant island across the bay from Miami, Florida, Fisher wanted a reliable route for his wealthy friends and others to drive south, in hopes that they would build winter homes on what he now called Miami Beach. Fisher’s idea for the “Dixie Highway” was unveiled in Atlanta at the fourth annual meeting of the American Road Congress in November 1914.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

Launching of the Dixie Highway

On April 3, 1915, Georgia governor John M. Slaton and his counterparts (or their representatives) from five other states met in Chattanooga, Tennessee, for the inaugural meeting of the Dixie Highway Association (DHA). While the new highway generated enthusiasm, selecting its route became a highly politicized task. Initially, Chicago, Illinois, was the northern terminus, but after Michigan joined the DHA in May, things became complicated. Fisher initially had conceived of a single route for the Dixie Highway from Chicago to Miami, but Michigan wanted Detroit included as well.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

In the midst of this debate, Georgia’s two members of the DHA played an important role. Macon Telegraph editor and owner William T. Anderson proposed that the DHA approve western and eastern divisions of the Dixie Highway where dual routes were warranted. Atlanta Constitution editor and owner Clark Howell also wanted to abandon the idea of a single highway and urged that the Dixie Highway be constructed as a system of roads in order to promote economic development in more communities.

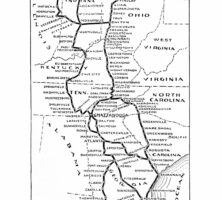

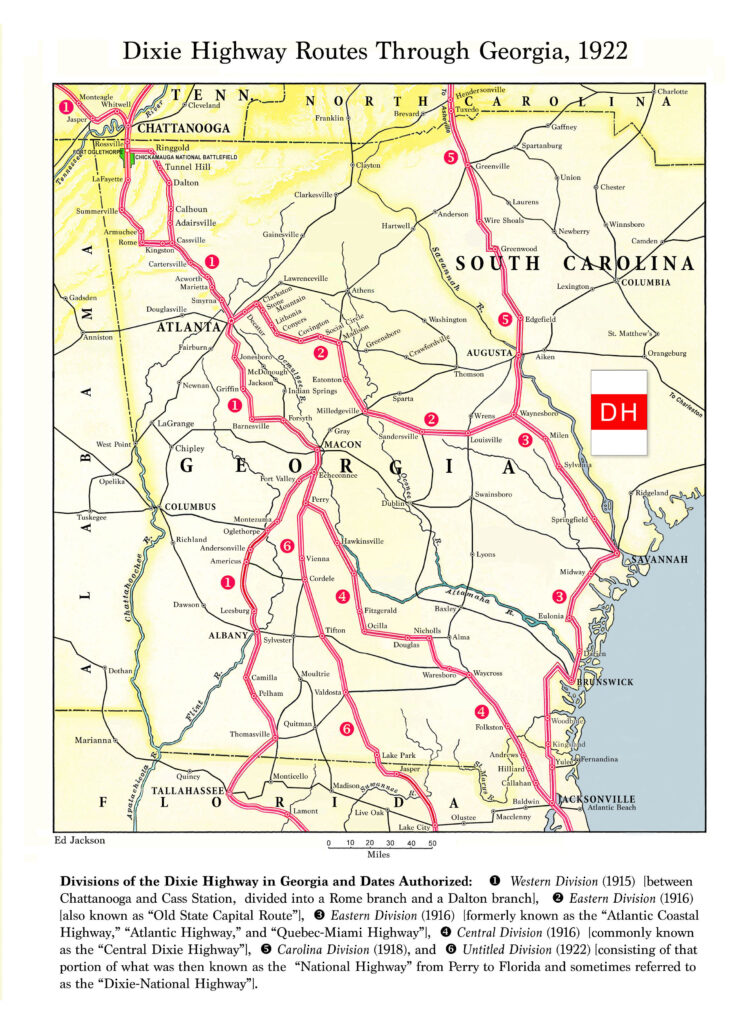

As a result, the Dixie Highway became a network with Sault Ste. Marie on the Canadian border as the northern terminus. From there, the highway extended southward through upper Michigan and then via ferry to Mackinaw, where the highway split into a Western Division that included Chicago and an Eastern Division that included Detroit. Following roughly parallel paths southward, the two divisions reunited at Chattanooga.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

Envisioning an influx of tourists, different cities and counties competed to be part of the Dixie Highway. In Georgia, rivalries became intense—especially between Rome and Dalton, each sending hundreds of supporters to the DHA’s initial meeting to argue the merits for including their city on the route. Dalton not only offered the shortest route from Chattanooga to Atlanta but also boasted that it was the “Battlefield Route” associated with Union general William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, which would attract Civil War tourism. Rome made a persuasive case that it had a larger population base and could build its portion more quickly than Dalton.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

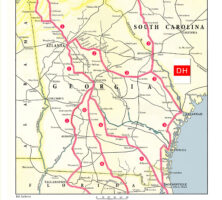

As a compromise, the DHA approved two routes south from Chattanooga—one through Dalton and one through Rome—with both routes converging near Cartersville, where they rejoined the Dixie Highway’s Western Division. This division then followed a route south in Georgia to Atlanta, Macon, Americus, Albany, and then on to Tallahassee, Florida. In 1916 the DHA approved a new Eastern Division running southeast from Atlanta to Waynesboro to Savannah, before continuing on to Jacksonville, Florida. That same year, a new Central Dixie Highway was added linking the Georgia towns Perry, Waycross, and Folkston, and then heading southward to Jacksonville.

Two years later, the DHA authorized a new Carolina Division running from Knoxville, Tennessee, to Asheville, North Carolina; Greenville, South Carolina; and Augusta and Waynesboro, Georgia, where it connected with Georgia’s Eastern Division. Instead of being a single highway, the Dixie Highway developed as a network of major divisions and connecting routes.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

Early Funding Challenges

The largest problem facing the DHA was a lack of funding. This meant that every county on the route had to fund, pave, and maintain its portion of the venture. This daunting challenge changed in July 1916 after Congress passed the Federal Aid Road Act offering federal grants for state rural roads—but only if a state would match the funding and create a state highway department with professional engineers to oversee spending of federal funds. One month later, Georgia governor Nathaniel E. Harris signed legislation complying with the federal requirements. Unfortunately, several years would pass before significant money actually became available for highway construction.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

World War I (1917-18) temporarily stalled highway construction, but following the war Georgia’s new State Highway Department (later Department of Transportation) took over building and maintaining state roads—including the Dixie Highway.

Driving the Dixie Highway

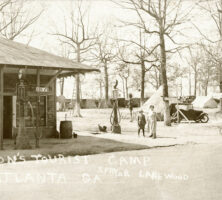

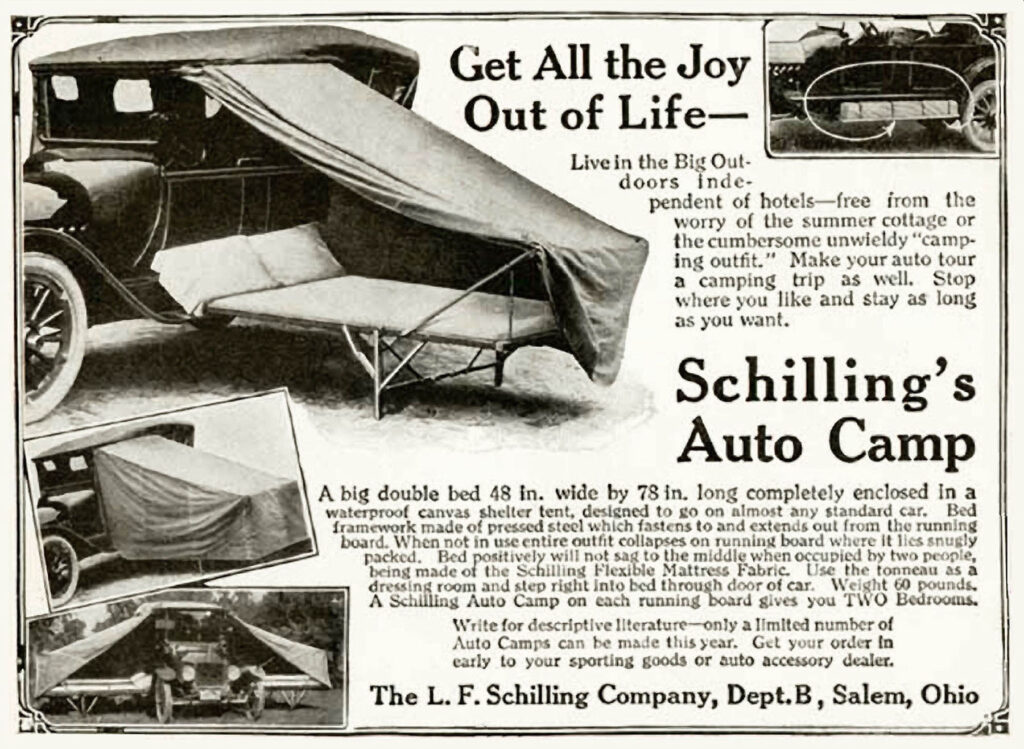

The development of affordable automobiles and the Dixie Highway meant that anyone with a car could head south for a summer or winter vacation. At that time, however, few of the amenities and necessities associated with travel today existed. While every town of any size had a downtown hotel with a restaurant, these establishments were not affordable for families traveling on a budget. So, many motorists packed a tent, cots, camping stove, and tin cans of food and gas, which allowed them to spend the night on the roadside, or in a church or school yard. Many local citizens were unhappy with the transient visitors—especially as they spent little money and often left a mess. To control problems by “tin can tourists,” some towns began setting up tourist camps. Here, for little or no charge, travelers could set up their tents, usually with access to water and a bathroom.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

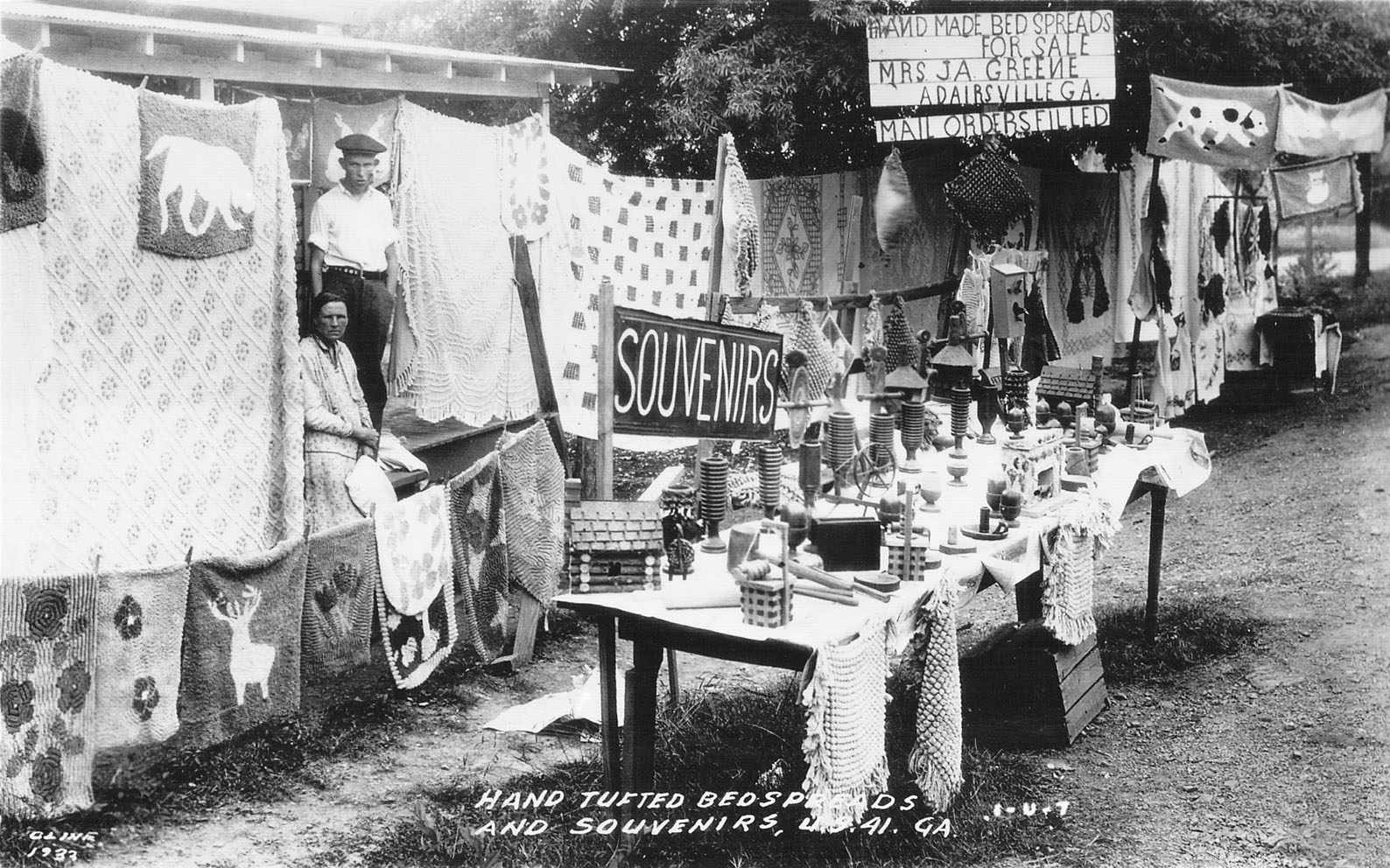

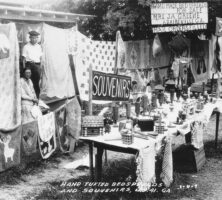

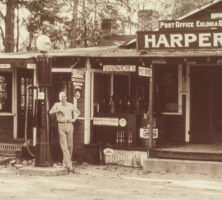

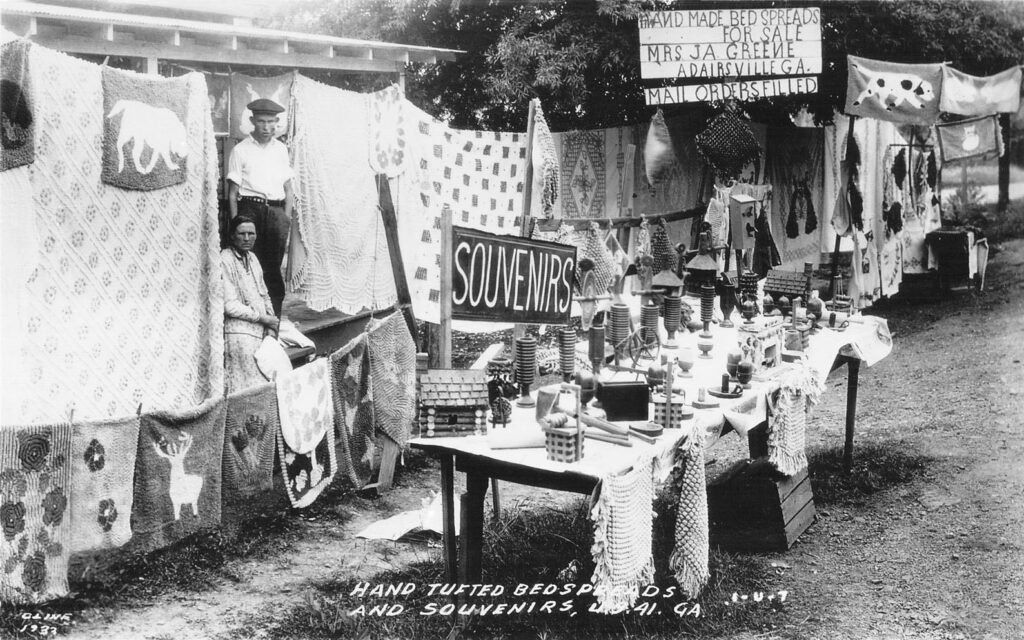

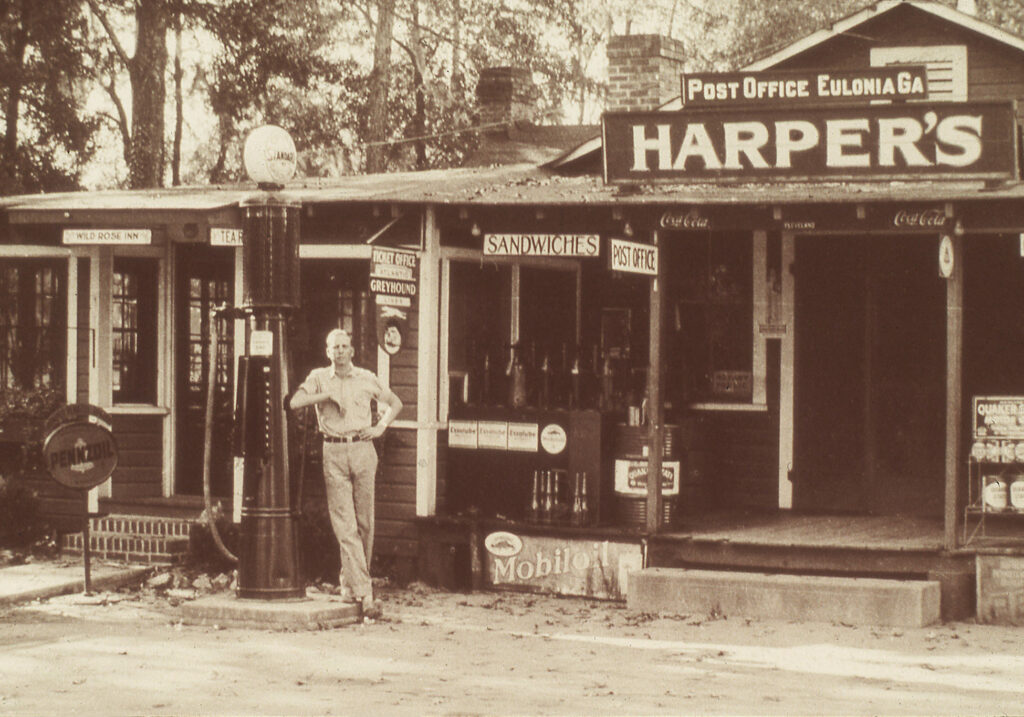

So popular was the Dixie Highway for midwesterners and Canadians that a host of Georgia entrepreneurs opened gas stations, garages, stand-alone restaurants, souvenir shops (where chenille bedspreads and pecan candy became popular), roadside produce stands, and other attractions for the traveling public. Soon, hundreds of “mom and pop” tourist courts offered overnight visitors a small cabin with a bedroom and bathroom.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

The Dixie Highway ceased to exist by that name in 1926, when federal and state highway officials replaced named trails across America with numbered highways. Because the Dixie Highway was not a single highway, its various divisions became parts of the new U.S. numbered highway system (most notably U.S. 1, 17, 19, 25, 27, 41, and 129), plus a variety of state-numbered highways.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

The Dixie Highway had a relatively short official life. But its roadbeds—now numbered highways—constituted important physical and cultural transportation corridors until the arrival of interstate highways. The highway brought tourists from other regions, spurring a host of entrepreneurial undertakings that made a dramatic impact on the culture and economy of the Georgia counties along its path. And, while driving through Georgia, many Florida-bound motorists discovered the Peach State’s diverse assortment of historical and scenic attractions, eventually helping to make tourism one of Georgia’s leading industries.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson