Georgia’s Lower Coastal Plain, an environmental region of the Coastal Plain Province, contains some of the state’s most well-known geographic features—the coastal barrier islands and the Okefenokee Swamp. The state’s lowest elevations and its highest percentage of wetlands—including tidal salt and brackish marshes, bottomland hardwood swamps, and the Okefenokee—are found in the Lower Coastal Plain.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

Geologists, biologists, and other scientists disagree on the extent of the area occupied by the region. In general, wildlife biologists and other experts refer to the Lower Coastal Plain as the area roughly covering a twenty-seven-county “ecoregion” designated as the Southern Coastal Plain. That region extends inland about sixty-five to seventy miles from the seashore. Its boundary stretches across the lower portion of the state from Screven County in southeast Georgia to Echols County to the southwest.

The topography of the Lower Coastal Plain is generally low, flat, and swampy where it borders the Atlantic, and grades to low rolling hills at the inner margin. It is at a lower altitude and has less relief than the Upper Coastal Plain. Agricultural and most other commercial activities in the Lower Coastal Plain are concentrated on its higher and drier ground. In inland areas of the Lower Coastal Plain, water depth fluctuates with rainfall and the seasons. The sandy soil tends to absorb streamflow, especially during drought, when the water table falls. The sand also actsas temporary storage space to absorb some of the flood flows.

Land cover in the region is mostly slash and loblolly pine, with oak-gum-cypress forest in some low-lying areas, and pasture for beef cattle.

Physiographic Districts

The Lower Coastal Plain contains several subregions, or physiographic districts, based on topography, geology, soil, flora, fauna, and other factors. The most notable of these districts are the Barrier Island Sequence and the Okefenokee Basin.

Photograph from John Whitehill

The Barrier Island Sequence includes primordial seashores and the present-day coastline. The area is composed primarily of a series of six prehistoric terraces. The parallel terraces were formed during the geologically recent Pleistocene epoch, also known as the Ice Ages, which began nearly 2 million years ago. The terraces represent primordial shorelines created by fluctuating sea levels. The old shorelines were similar to Georgia’s present-day seashore, marked by sweeping salt marshes, tidal creeks, and short, wide barrier islands separated by deep sounds.

At the beginning of the Pleistocene, most of southeast Georgia, a portion of southwest Georgia, and probably the entire Florida peninsula were beneath the sea and part of the continental shelf. The Pleistocene was a time of changing sea levels as the great continental glaciers of northern North America and Eurasia advanced and retreated, causing sea levels to rise and fall.

The old shorelines, or terraces, formed where the fluctuating sea levels temporarily stopped or stabilized. Today, in cross section, the Barrier Island Sequence district resembles a series of steps, or terraces, descending to the sea. The terraces are visible as sand ridges and account for some relief in the otherwise flat and low-lying Lower Coastal Plain.

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The furthermost of the Pleistocene shorelines is known as the Wicomico, which lies up to sixty miles west of the present Atlantic Ocean shore and developed when the sea level was approximately 100 feet higher than the present level. After the Wicomico barrier, several sequences of barrier islands occurred: Penholoway, which developed when sea level was about 75 feet above present level; Talbot, 40-45 feet; Pamlico, 25 feet; Princess Anne, 15 feet; and Silver Bluff, 5 feet.

In some cases the sand ridges influence the present-day courses of several Georgia rivers. The Ogeechee and Altamaha rivers break through these ridges and flow directly to the sea, but the Satilla River makes a twenty-mile dogleg in Wayne County, where it is trapped between the Penholoway and Talbot beach complexes, before it breaks through the latter to the sea. The St. Marys River makes an even larger doglegin the opposite direction. As a result, there is a large poorly drained area in Charlton and Ware counties.

The Wicomico shoreline featured an unusually large barrier island, now called Trail Ridge. It obstructed the drainage of a great salt marsh more than 700 square miles in size. That basin became the present-day Okefenokee Swamp.

Today’s Barrier Islands

Georgia meets the Atlantic Ocean along the sandy beaches of the present-day barrier islands, known as the Sea Islands or the Golden Isles. Scientists refer to them as barrier islands because they form a barrier between the sea and the land. The current configuration of Georgia’s shoreline is only the most recent in a long series of changing shorelines.

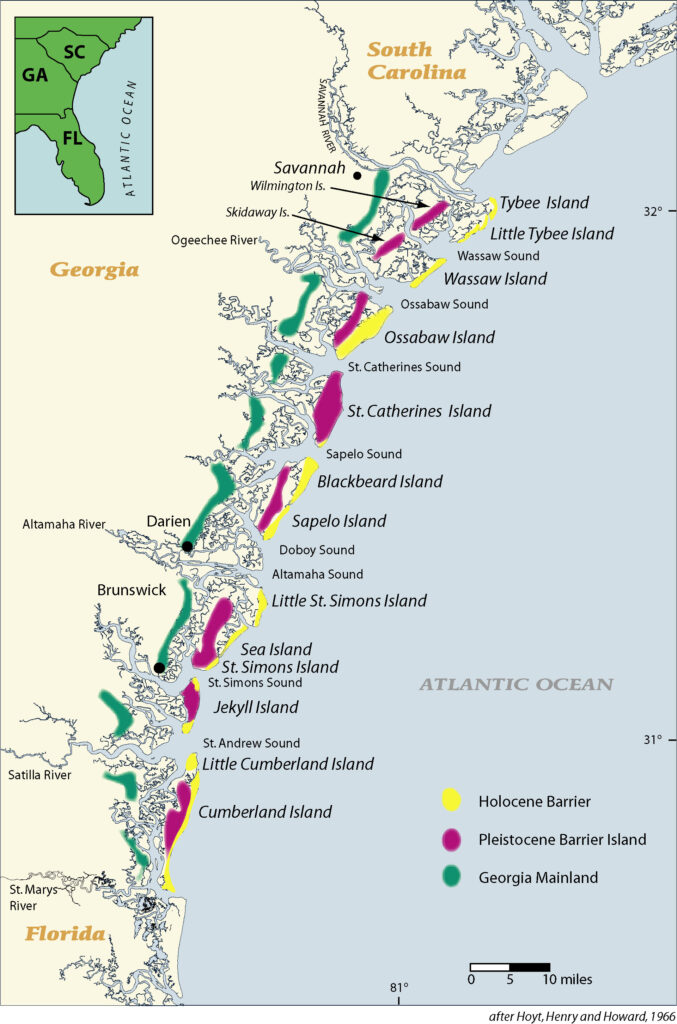

Courtesy of V. J. Henry

The islands are composed basically of dune and beach-ridge sands. They were shaped—and are still being altered—by wind, waves, currents, tides, and a slowly rising or stable sea level. From north to south along Georgia’s 100-mile-long coast, the barrier islands are Tybee, Little Tybee, Wassaw, Ossabaw, St. Catherines, Blackbeard, Sapelo, Wolf, Little St. Simons, St. Simons, Sea, Jekyll, Little Cumberland, and Cumberland. (Skidaway Island, near Savannah, is said to be an inshore barrier island. It lacks the wide, sandy beach typical of Georgia’s outer barrier islands.)

Separated from the mainland by a four- to six-mile-wide band of salt marsh, tidal creeks, and estuaries, Georgia’s barrier islands are under various types of ownership and management.

Jekyll, Sea Island, St. Simons, and Tybee islands are developed and connected to the mainland by bridges and causeways. Much of Jekyll is a state park.

The other barrier islands are accessible only by boat. Of these, Blackbeard, Wassaw, and Wolf islands are national wildlife refuges. Little Tybee, Ossabaw, and Sapelo are owned by the state of Georgia. The Cumberland Island National Seashore is managed by the National Park Service. Little Cumberland, Little St. Simons, and St. Catherines are privately owned.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

Georgia’s barrier islands, as well as those of southern South Carolina and northern Florida, are of two generations. The older islands are called Pleistocene in reference to the geologic period in which they were formed. Examples of Pleistocene islands include Sapelo and St. Simons, formed 35,000 to 40,000 years ago. The “younger” barrier islands are referred to as Holocene. Examples include Little St. Simons, Sea, and Wassaw islands, which formed 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. The Pleistocene islands tend to be flatter with well-developed soils, whereas the Holocene islands have many dune ridges and poor soils.

The barrier islands today typically have four ecosystems: sweeping salt marshes, maritime forests, freshwater sloughs, and hard-packed sandy beaches. On the islands’ western sides are the vast tidal salt marshes, composed mostly of the salt-tolerant plant Spartina alterniflora, or smooth cordgrass. The coastal marshes, tidal creeks, and connecting estuaries are important nursery areas for fish, crab, shrimp, and other marine species.

At the edge of the marsh, the maritime forest begins. The transition from marsh to forest is abrupt. The forests of Georgia’s islands often are more extensive and better developed than those of other U.S. barrier islands. Canopies of Georgia’s mature maritime forest are dominated by live oaks festooned with Spanish moss. Other large canopy trees include southern magnolias, pines, and cabbage palms. Pine stands are usually found in the younger, southern ends and ocean sides of the island forests. The trees often are intertwined with woody vines. Forming the forest understory are shrubs and such smaller trees as American holly, cherry laurel, redbay, saw palmetto, sparkleberry, wax myrtle, and yaupon holly.

Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Freshwater sloughs in the forest interior usually are seasonal or year-round ponds filled with rainwater. The wetlands provide important habitat for alligators, water birds, otters, and other island wildlife. On islands with significant human development, such ponds, if not drained and filled, often are used as water hazards on golf courses.

Barrier-island beaches are characterized by wide, intertidal, gently sloping expanses of hard-packed, fine white quartz sand. The beaches often extend from the normal high-tide line to about thirty feet below the low-tide line. Facing a beach on its landward side is a wall of young “primary sand dunes,” sculpted by wind and waves. Their faces are raw and steep. These primary dunes are the island’s first line of defense against the sea. Morning glories, pennyworts, sea oats, and other plants grow on the dunes and help to stabilize them.

Farther back stand older, larger, steeper dunes of fine, soft sand. On some barrier islands, such as on Cumberland, they rise more than fifty feet and provide backup protection to the primary dunes against wind and storms. Between the primary and rear dunes are meadows of grasses, sedges, and such shrubs as wax myrtle, which attract seed-eating birds, rabbits, and other small mammals.

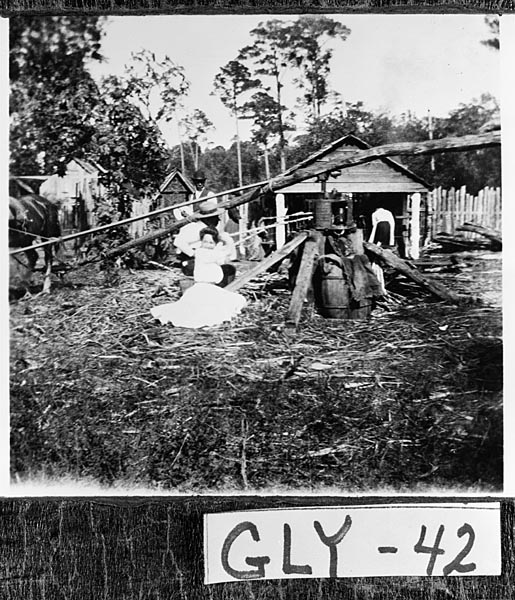

The islands and the adjacent coastal mainland have a long history of human alterations. Native Americans hunted and fished there and cultivated beans, corn, melons, and squash; a Spanish mission period during the 1500s-1600s included crops of artichokes, citrus, figs, olives, onions, and peaches; and a plantation agriculture economy in the late eighteenth through the nineteenth centuries produced indigo, rice, Sea Island cotton, and sugar cane.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, wealthy northerners purchased several of Georgia’s barrier islands and turned them into private resorts and retreats. The private owners, for the most part, kept their islands undeveloped.

Coastal Industry

Coastal fisheries and forest resources support a number of industries engaged in processing, manufacturing, and marketing seafoods and wood products. In general, tourism and recreation, shipping at the ports of Savannah and Augusta, papermaking, commercial fishing, and forestry have been the most important economic activities of Georgia’s modern coast. Over the decades the pulp and paper industry expanded at the expense of the fishing industry, which has suffered greatly from pollution caused by the paper mills.

Current Threats to the Coast

Growth projections for Georgia’s coast indicate a 20 percent population increase per decade over the next few decades. Thanks to the protected status of most of Georgia’s barrier islands, the majority of them should be spared many problems typically associated with rapid and extensive unplanned development.

Photograph by William Folsom. Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Nevertheless, as sea levels rise due to global warming, the erosion of barrier island beaches is expected to increase. Already, expensive renourishment projects are needed to maintain recreational beaches on Sea Island and Tybee Island. Approximately 55 percent of the nineteen miles of beach shoreline on Jekyll, Sea, St. Simons, and Tybee islands have been reinforced with either concrete sea walls or revetments of granite boulders in an effort to control natural erosion. The structures destroy the aesthetic quality of beaches and leave little or no beach area available at hightide for recreation.