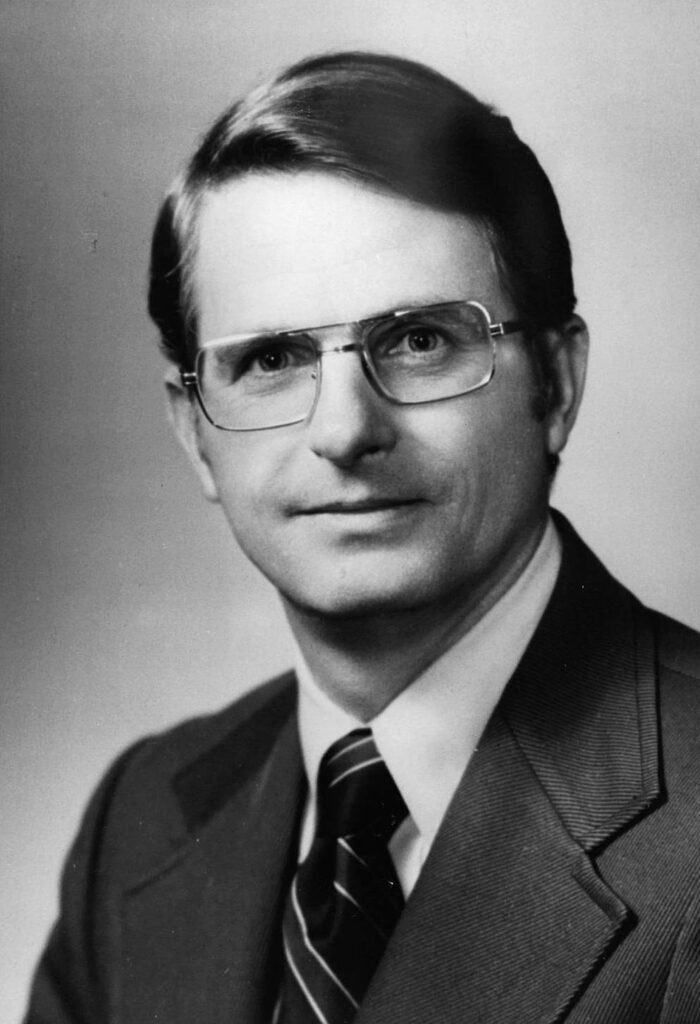

Zell Miller played a significant role in Georgia politics during the last half of the twentieth century, serving as mayor, state senator, lieutenant governor, governor, and U.S. senator. He earned both praise and criticism for his willingness to adapt to changes in the state’s political climate and is best remembered for his innovative and far-reaching strides to improve education at all levels within the state.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Early Life

Zell Bryan Miller was born on February 24, 1932, in Young Harris (in Towns County), to Birdie Bryan and Stephen Grady Miller. When the infant Zell was just seventeen days old, his father died. His widowed mother raised her son and daughter, Jane, alone. In Young Harris, located in the north Georgia mountains, Miller’s mother built a home for herself and her children with rocks she had hauled from a nearby stream, and that house became symbolic of Miller’s rugged independence. After graduating from Young Harris College, Miller continued his education at Emory University in Atlanta but found shortly after arriving that his studies lacked focus.

Miller enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1953 and later attributed his success to both the discipline he learned as a marine and the independence he learned from his mother. He married Shirley Carver in 1954, and the couple had two sons. In 1956 Miller enrolled at the University of Georgia, where he earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in history, with historian E. Merton Coulter serving as his mentor. In 1959 he took a teaching position at Young Harris College and returned to his hometown as a professor of history and political science.

Early Political Career

While still a faculty member, Miller was elected mayor of Young Harris, a post he held for one term (1959-60). He was then elected to two terms as a state senator, representing first the Fortieth District (1961-63) and then the Fiftieth District (1963-65). A few years later, he took leave from his teaching responsibilities to serve as executive secretary for Lester Maddox during Maddox’s governorship (1968-71). Maddox was elected on a pro-segregation platform, but Miller has been credited with exerting a moderating influence on the governor. Miller encouraged Maddox to make African American appointments in his administration and to focus on building the state’s higher education system, advice that Maddox followed.

During the 1970s Miller was twice named a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, once in 1972 and again in 1976. In 1971 he was appointed executive director of the Democratic Party in Georgia and served in this capacity until 1973, when he became a member of the State Board of Pardons and Paroles. He served on the board until 1975.

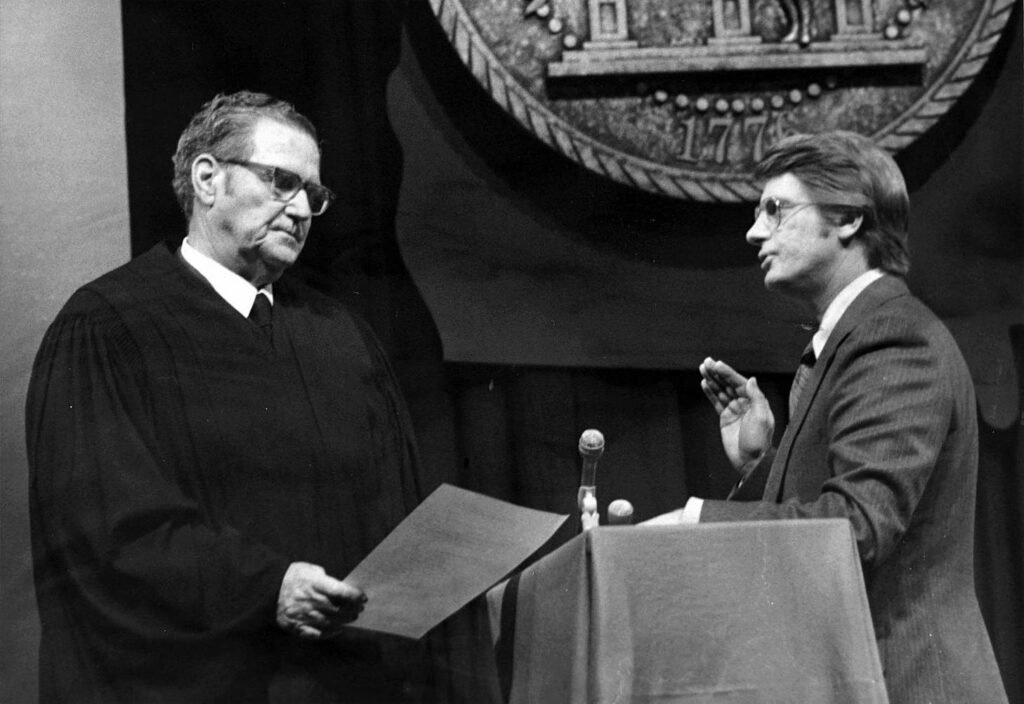

Beginning in 1975, Miller spent sixteen years as lieutenant governor of Georgia, longer than anyone else. In 1980, bolstered by winning his second race for statewide office, he ran for the U.S. Senate but lost the Democratic primary to incumbent senator Herman Talmadge. During the campaign, Miller raised questions about Talmadge’s past support for segregation and his ethical standards, which led some observers to believe that Miller was a political liberal. In the November general election, Talmadge lost to Republican Mack Mattingly, and several Democratic leaders blamed Miller for having weakened Talmadge’s position during the primary race.

Image from Georgia Secretary of State

Over the next ten years as lieutenant governor, Miller worked to build his leadership skills. As presiding officer of the state senate he made both friends and enemies, and he regularly sparred with Tom Murphy, the longtime Speaker of the state house. While both Miller and Murphy were Democrats, they often clashed over issues. Miller was sometimes able to rally bipartisan support for his side, and as lieutenant governor he appointed some Republicans to committee chairmanships.

In 1990 Miller ran for governor. In the Democratic primary, he faced competition from former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young and state senator Roy Barnes. Miller and Young were ultimately forced into a runoff, from which Miller emerged as the Democratic nominee. As a candidate Miller focused on education and pledged that he would only serve one term if elected governor. In the general election, he beat his Republican opponent, state senator Johnny Isakson, by more than 100,000 votes.

Governorship

As governor, Miller campaigned to establish a state lottery. He supported legislation that restricted lottery proceeds to funding for pre-kindergarten programs, capital and technology enhancements for Georgia schools, and most significant, the HOPE Scholarship program. HOPE scholarships provide full tuition at any state college or university to any Georgia resident who graduates from high school with at least a B average. In 1992 voters ratified the lottery amendment, and the lottery-funded programs were launched in 1993. Miller also signed legislation that gave Georgia the toughest repeat offender sentencing guidelines in the nation.

In 1992 Miller was critically important to Arkansas governor Bill Clinton’s campaign to secure the Democratic U.S. presidential nomination. Miller and Clinton seemed to be natural allies—both were active, moderate governors of southern states who had won office by promising to improve education. Further, they shared political advisors. Clinton’s 1992 campaign strategists had worked for Miller in 1990. After Clinton won the presidential primary in Georgia, he invited Miller to give one of the three keynote speeches at the Democratic National Convention. Placards reading “Give 'Em Hell, Zell” were distributed among the delegates as Miller gave a speech that was critical of U.S. president George H. W. Bush’s administration. Later that year, Miller again actively campaigned for Clinton, who carried Georgia in his win of the November presidential election. After Miller’s success in state and national politics, it surprised few when he announced that he would seek a second gubernatorial term.

Miller’s reelection campaign in 1994 was not easy. In spite of his accomplishments, Miller had made political enemies. He had tried, unsuccessfully, to have the Confederate battle emblem removed from the state flag. His close connection to President Clinton became a burden when the president’s popularity sagged. Finally, the fact that Miller had retreated on his pledge to serve only one term as governor irked some voters. His Republican opponent in 1994 was Guy Millner, a millionaire who was willing to spend his own fortune to finance his campaign. Miller ultimately prevailed but only by a narrow margin—he received 51.05 percent of the votes, and Millner received 48.95 percent, a margin of just 32,555 votes.

During his second term as governor, Miller continued his efforts to improve all levels of education in Georgia by making investments in technology, buildings, and human resources. Georgia became known as a national leader for innovative programs, and teachers’ salaries rose to near the top for the region. In the last year of his governorship, he secured private funding to distribute classical music CDs to the family of every baby born in the state. (At the time, research indicated that playing classical music to newborns may increase their intelligence.) Miller also ordered state agencies to make budget cuts and redistributions—unusual for a state in good financial shape. His reasoning was that state agencies likely had become wasteful in their spending during the prosperous 1990s. Miller left office in early 1999 with an 85 percent approval rating from Georgians—a record high for a Georgia governor and a rating that made him the most popular governor in the nation.

Author

Despite the demands of holding political office, Miller found time to write several books about Georgia. His first book, The Mountains within Me (1976), is partly a memoir of his early years, partly a history of Young Harris (both college and community), and partly a broader examination of the culture, folkways, and politics of the north Georgia mountains. Twenty years later, while governor, he wrote another partially autobiographical work, Corps Values: Everything You Need to Know I Learned in the Marines (1996). Each of its twelve chapters is devoted to a particular trait he developed during his years in the Marine Corps, such as “Courage,” “Neatness,” “Discipline,” and “Pride.”

Between these two books, Miller wrote two other books about the state. Great Georgians, published in 1983 to mark the 250th anniversary of Georgia’s founding, is a collection of biographical sketches of prominent historical figures. In 1996, the same year he published Corps Values, Miller released They Heard Georgia Singing, a compendium of Georgia musicians. Miller was a lifelong supporter of music, and his leadership had been instrumental in the creation of the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, which was established in 1979, as well as the associated museum in Macon, which operated from 1996 until 2011. The Zell Miller Center for Georgia Music Studies at the museum housed the Hall of Fame’s archives and library.

In 2009 Miller published Purt Nigh Gone: The Old Mountain Ways, which chronicles such aspects of Appalachian history and culture as the Cherokee Indians, the gold rush, foodways, moonshine, music, and religion.

Senate Career

In 1999 Miller reassumed his teaching career with affiliations at Young Harris College, the University of Georgia, and Emory University. The following year Governor Roy Barnes appointed Miller to the U.S. Senate after Senator Paul Coverdell died. Miller’s appointment was to fill the seat for four months, an interim period of time between Senator Coverdell’s death and the next scheduled federal election. Miller ran for the seat in the November election and won it for the remaining four years of the six-year term.

Miller pledged to carry on the conservative tradition of the late Senator Coverdell, who was a Republican. Many Democratic leaders in Congress thought that having the popular former governor join their ranks would help them regain the majority. However, Miller proved to be a frustration to the Democrats for the rest of his term. He cosponsored U.S. president George W. Bush’s 2001 tax cuts and was adamantly in support of President Bush on the issues of homeland security and the deployment of troops to Iraq at the start of the Iraq War (2003-11). He was also vocal in criticizing the lack of support for the president by the Democratic Party’s leadership.

As his Senate career progressed, Miller was often at odds with his party’s leadership and increasingly supportive of Republican initiatives. In 2004 he published a critique of the national Democratic Party leadership, A National Party No More: The Conscience of a Conservative Democrat, which became a national best-seller in the months before the presidential election that year.

Miller’s conservative turn aroused the ire of fellow Democrats, many of whom were incensed when he accepted an invitation to address the 2004 Republican National Convention as a keynote speaker. In the days after the speech Miller campaigned for Bush in a number of venues, though he never renounced his party affiliation.

In January 2005 Miller retired from the Senate and returned to Georgia, where he continued to write and resumed his teaching career. Miller’s final book, A Deficit of Decency (2005), expanded on his earlier critique of the Democratic Party, suggesting that the party had become unmoored from traditional, Christian values. In August 2005 President Bush appointed Miller to the American Battle Monuments Commission, which maintains U.S. military cemeteries and monuments in other countries and commemorates the contributions of U.S. veterans who served in World War I (1917-18) and later wars.

In 2008 the Zell B. Miller Learning Center at the University of Georgia was dedicated in his honor. In 2017 Miller’s family announced that he suffered from Parkinson’s disease and was retiring from public life. He died in Young Harris on March 23, 2018, at the the age of eighty-six.