Seeing Georgia: Changing Visions of Tourism in the Modern South

How the state transformed itself from a way station along the route to Florida into a popular tourist destination.

Introduction

Since the 1800s travelers have come to Georgia to enjoy natural landscapes, recreation, and historic sites. For nearly as long, competing interests have fought for the right to preserve, alter, or exploit these sites. Debates over race, class, and accessibility have also shaped the development of tourism in the state.

Seeing Georgia: Changing Visions of Tourism in the Modern South investigates how the state transformed itself during the twentieth century from a way station along the route to Florida into a popular tourist destination. It highlights six popular destinations in Georgia and considers questions of access, preservation, and economics. The exhibition also explores the professionalization of the tourism industry and the roles that state and local governments have played in promoting Georgia to travelers. And finally, it examines the modern amenities that shape the experience of the modern tourist, from the improvement of roadways to the development of roadside culture and accommodations.

This exhibition was developed in 2015 by the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies at the University of Georgia in Athens.

Hitting the Road

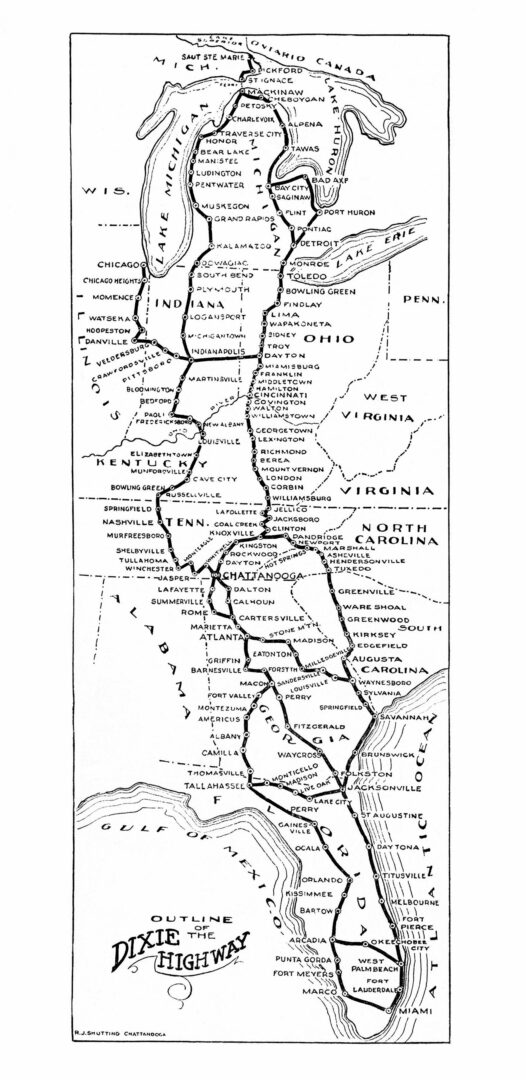

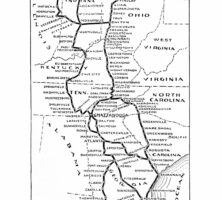

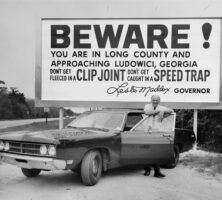

The Good Roads Movement (1880s-1920s) spurred unprecedented social and political changes in the South. In 1904 only 4 percent of public roadways—macadamized or graded gravel roads—were classified as improved. Dirt roads had long plagued farmers in their attempts to move crops from rural farms to markets. By 1908, when small numbers of northern motorists began to trickle to the South, a movement for better roads evolved into a campaign to create interstate tourist highways. New South boosters like Atlanta mayor Robert F. Maddox and Atlanta Constitution editor Clark Howell expected improved roads to further unite the North and South and boost the South’s economic vitality through increased tourism and business.

Construction of the National and Capital highways connected Georgia with major northeastern cities, while the Dixie Highway connected Georgia to the Midwest. In 1956 U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, authorizing the construction of 41,000 miles of roadways. Largely funded with federal fuel taxes, interstates were built with consistent standards, wide lanes, and paved shoulders, and they consisted of at least four lanes to accommodate vehicle speeds of up to seventy miles per hour. The new system quickly became the primary route for tourist traffic.

Roadside Culture

Tourism by automobile took hold in the United States during the early 1900s. After a long day of traveling, most autocampers created their own accommodations for the night by stopping alongside the road and attaching a canvas tent to the side of the vehicle. As the travel industry boomed, travelers faced ever-growing options for roadside lodging. Soon towable tent and pop-up trailers were mass produced, and no-frills campsites sprang up along major tourist routes like the Dixie Highway. In 1925 approximately 500,000 automobiles from outside the region traveled through the Southeast, carrying an estimated 1.9 million visitors.

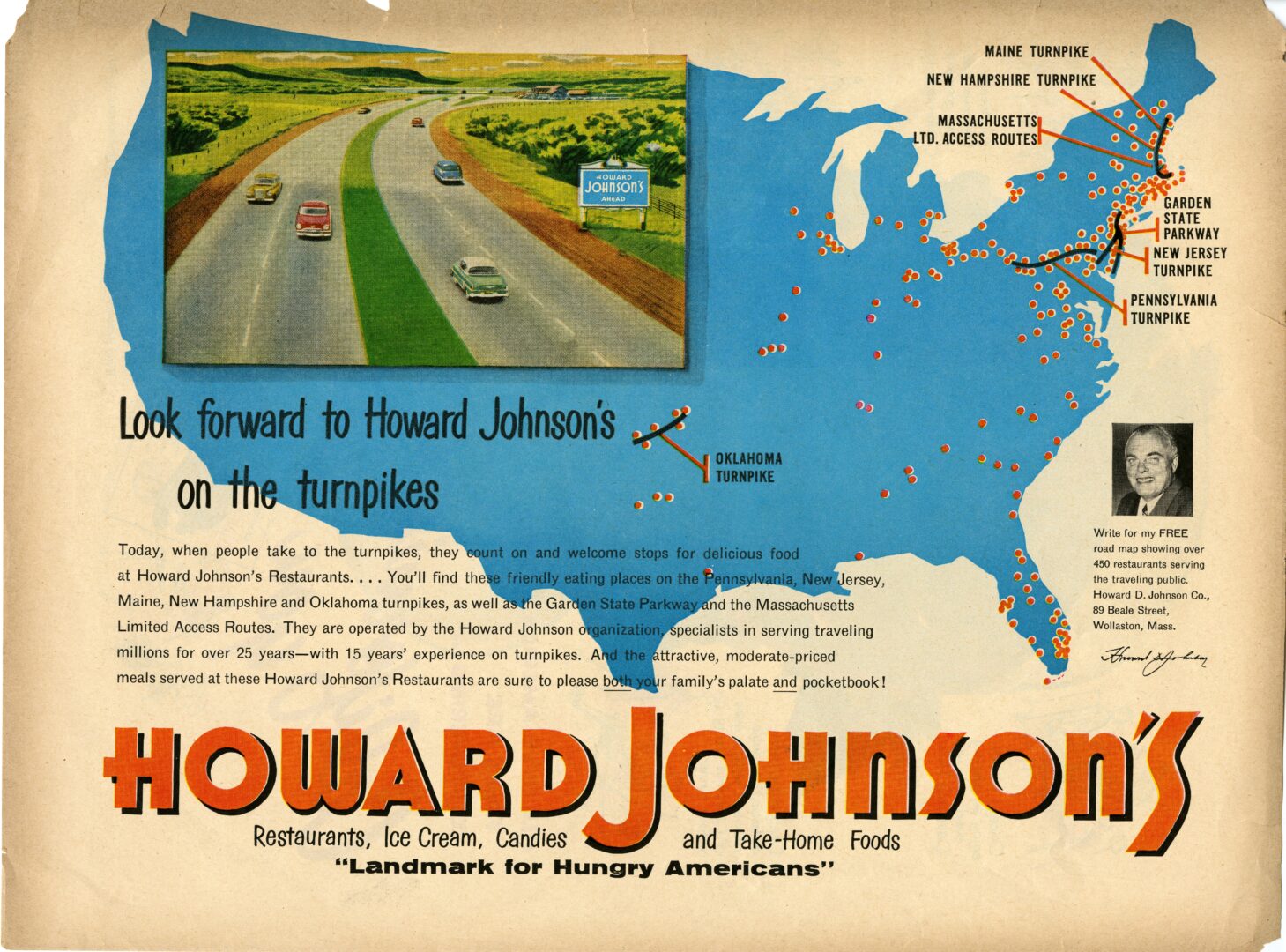

As long-distance road vacations became more common, the need for inexpensive, easily accessible overnight accommodations grew. In the era after World War II (1941-45), motels built near main routes lured tourists with the promise of swimming pools, color televisions, and air-conditioned rooms. By the late 1960s many independently owned motels were overcome by the introduction of chains like Holiday Inn and Howard Johnson, which offered more standardized accommodations.

Entrepreneurs in towns along the route also developed offerings to capture tourist dollars. Some took in boarders, while others opened roadside stands selling produce. In 1937 Williamson S. Stuckey Sr. opened the first Stuckey’s roadside convenience store along Georgia Route 23 in Eastman, offering cold drinks, snacks, souvenirs, and pecan candy. By the 1960s more than 350 Stuckey’s locations were in operation across the Southeast.

Until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which guaranteed all Americans access to public accommodations, many motels, campgrounds, and other establishments were segregated, restricted to “whites only.” As a result, African American travelers had very few choices for overnight accommodations in southern states. Published annually from 1936 until 1967, The Negro Travelers’ Green Book served as a guide to assist African Americans on the road. Created by Victor H. Green, a civic leader in Harlem, New York, the book provided lists of gas stations, restaurants, motels, and other businesses in each state that offered services to Black travelers. Eventually published with the aid of the U.S. Travel Bureau, more than 15,000 copies were sold annually.

Stay and See Georgia

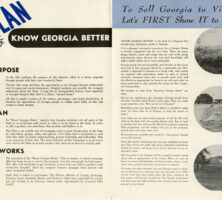

In the early twentieth century, Georgia had no state-run division of tourism and no annual allocation for marketing local attractions. Beginning in the 1940s, state officials set their sights on turning Georgia into a “stop over” destination in hopes of capturing some of the tourist dollars headed further south.

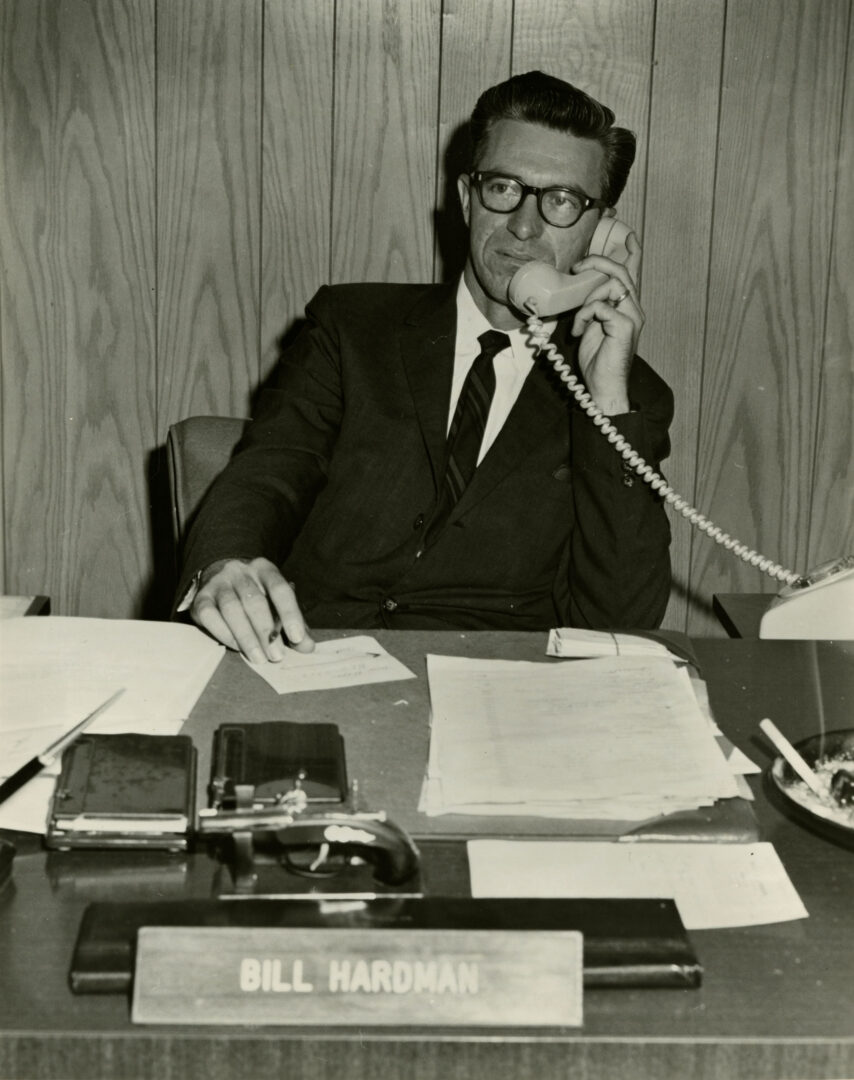

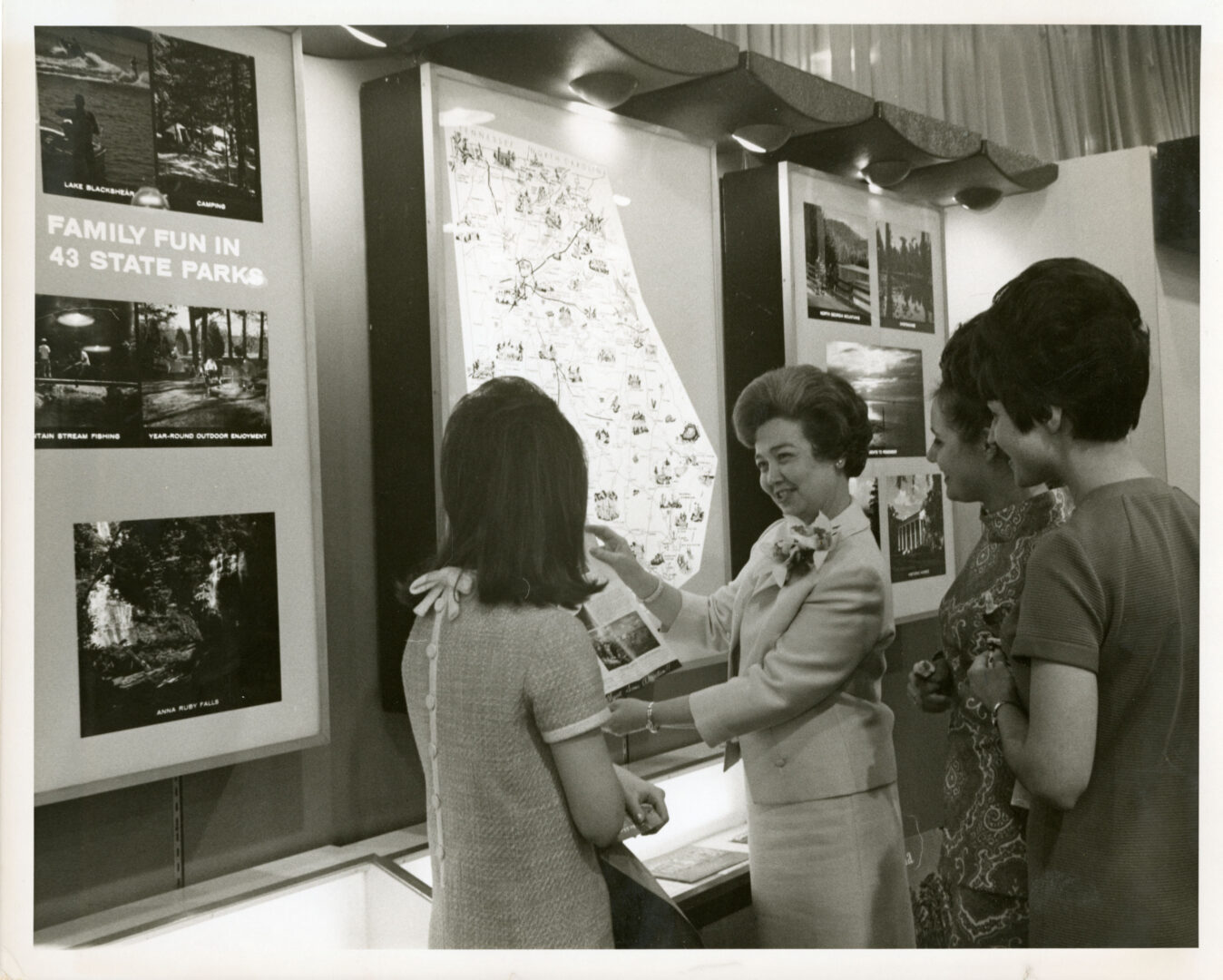

The administration of Georgia governor Ernest Vandiver Jr. saw tourism as integral to the state’s growing economy, and in 1959 Bill Hardman was named director of Georgia’s newly created Tourist Division, part of the Department of Commerce. Hardman, along with Abit Massey, director of the Department of Commerce, was instrumental in the development of the Tourist Division and in the creation of welcome centers across the state, as well as clever advertising campaigns that convinced people to “Stay and See Georgia.”

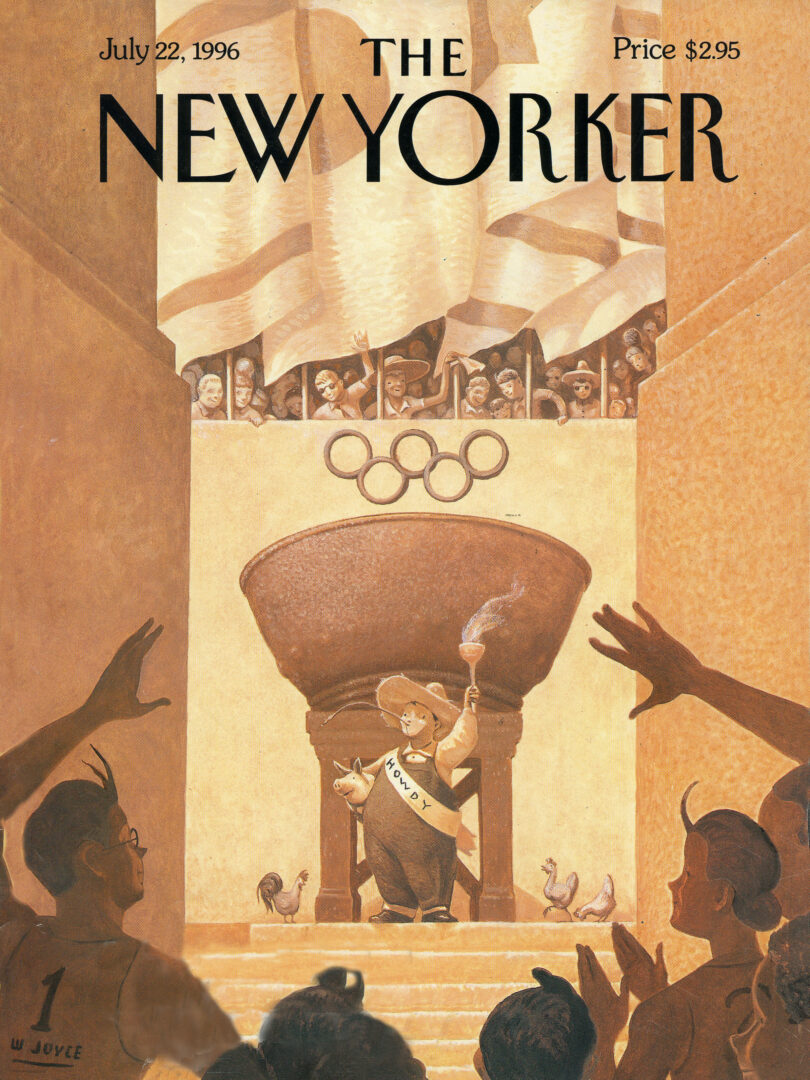

By 1970 Georgia had transformed from a state with no budget for tourism into a state with one of the largest promotional budgets for tourism in the nation. This investment reverberated through later decades, notably when the state’s reputation for southern hospitality played a role in Atlanta’s selection as the host city for the Centennial Summer Olympic Games, enticing more than 2 million tourists to Georgia in 1996. By 2015 the Tourism Division—part of the Georgia Department of Economic Development—brought in more than $57.1 billion dollars annually.

Sites of Wellness, Wilderness, and Reinvention

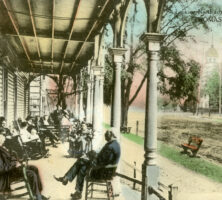

The diversity of Georgia’s tourist sites has long appealed to a wide range of travelers. During the late nineteenth century, many wealthy northern elites looked to the South for an escape from the winter cold, and their preoccupation with health, largely inspired by the rise of scientific rationalism, led to the creation of southern health resorts.

In 1874 physician Thomas Spalding Hopkins touted the benefits of south Georgia’s dry climate for improving respiratory ailments, and Thomasville soon became known as the “Winter Resort of the South.” Similarly, Indian Springs became a bustling resort town with its promise of healing mineral water, while Warm Springs offered a natural hot spring believed to cure ailments. Tourists seeking a healthful respite and scenic views also flocked to Tallulah Falls in the north Georgia mountains.

Meanwhile sites offering natural beauty captivated early auto tourists. In response to this rising trend, Georgia established a state park system in 1931 with the creation of Indian Springs State Park and Vogel State Park. The New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps was integral to the construction of facilities at both sites. During the 1930s and 1940s Georgia’s park system increased from 500 to 30,000 acres, and in 1972 the legislature established the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to operate sixty-three state parks and historic sites. By 2006 nearly 15 million people visited the parks annually. Jekyll Island State Park and the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge are among the most popular destinations in the state.

Since the mid-twentieth century some sites in Georgia, including Helen and Stone Mountain, have struggled to balance historic truth and commercial appeal. While tourism in Georgia once consisted mainly of solemn visits to war memorials, many destinations today openly embrace commercial amusement to create a marketable identity that appeals to a culturally diverse audience.

Tallulah Falls: Resort or Resource?

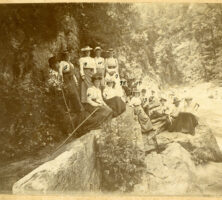

Remarkable vistas, ample opportunities for recreation, and access to healthful, cool air and water made Tallulah Falls irresistible to tourists in the nineteenth century. The completion of the nearby railroad’s expansion in 1882 and construction of several hotels during the 1890s had newspapers foretelling that Tallulah Falls was “destined to be the resort of the South.”

In 1909 the Georgia Power Company, recognizing the potential for generating electric energy by damming the Tallulah River, began acquiring land tracts around Tallulah. Soon the Tallulah Falls Conservation Association (TFCA), led by Helen Dortch Longstreet, organized to stop the construction of a dam, and to lobby state officials to create a public park instead. Despite their efforts, the dam was completed in 1913 and was the South’s largest hydroelectric development at the time. The dam’s construction, along with with a fire that destroyed Tallulah in 1921, impeded tourism, but a new type of attraction soon emerged.

Second homes and campgrounds replaced the once booming hotels and boarding houses, and tourists enjoyed fishing, boating, and swimming in the lake. On October 27, 1992, Georgia governor Zell Miller announced the creation of Tallulah Gorge State Park, including the dam, lake, gorge, and 2,710 acres of surrounding wilderness, as a joint venture between the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Georgia Power Company.

The Red Hills: From Cotton to Quail

With its convenient railway access, pleasant surroundings, and a dry climate believed to be healthful, the Red Hills region in southwest Georgia drew northerners during the winters of the late nineteenth century. These tourists more than doubled the local population. Depressed cotton prices in the post-Reconstruction era dropped property values, and soon visitors began buying up defunct cotton plantations and converting them into private hunting resorts.

By the 1930s south Georgia faced a great quail drought, owing to the loss of natural habitats and overhunting. Landowners turned to ecological experts like Herbert L. Stoddard and Eugene Odum to investigate this problem and suggest means for restoring the population. By the 1950s the two scientists had formed a relationship with Robert W. Woodruff, who implemented Stoddard’s guidelines for maintaining the quail population on his Baker County plantation, Ichauway. Today Ichauway serves as the outdoor research lab for the Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center.

These research efforts and the transfer of once private hunting property to nonprofit foundations and government entities made the Red Hills more accessible to the general public, and sport hunting expanded among the middle class in the years that followed. In 2012 Red Hills hunting plantations generated $147.1 million per year and employed more than 1,400 locals full time. In that same year Georgia ranked number one in the nation for attracting out-of-state hunters.

Jekyll Island: From Millionaires to the Masses

Once called the richest, most exclusive club in the world, Jekyll Island was a playground for northern capitalists during America’s Gilded Age. From its beginning in 1888 the Jekyll Island Club was host to such prominent industrialists as the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts, who were among the original fifty-three members of the club. The Great Depression of the 1930s and onset of World War II (1941-45) caused memberships to dwindle, and 1942 marked the club’s final season. Georgia governor Ellis Arnall soon thereafter appointed a commission to investigate the purchase of Georgia’s coastal islands for use as state parks.

Georgians, eager to enjoy an accessible in-state beach within reach of the average vacationer, largely supported the state’s proposal to purchase Jekyll Island. Though some politicians opposed the purchase, questioning whether the state belonged in the beach resort business, others hoped to capture tourist traffic headed further south. The state purchased the island for $675,000 and on October 7, 1947, renamed the property Jekyll Island State Park. Initially segregated, the island’s beaches were later integrated in 1964.

In 1950 the state legislature established the Jekyll Island Authority (JIA) to administer and promote tourism on the island, with the stipulation that no more than one-third of the property could be developed. (In 1953 the percentage of protected land increased to one-half, and in 1971 it dropped back to 35 percent.) Today, the JIA continues to maintain the delicate balance of supporting free enterprise and preserving the natural environment.

Okefenokee Swamp: A Defiant Wilderness

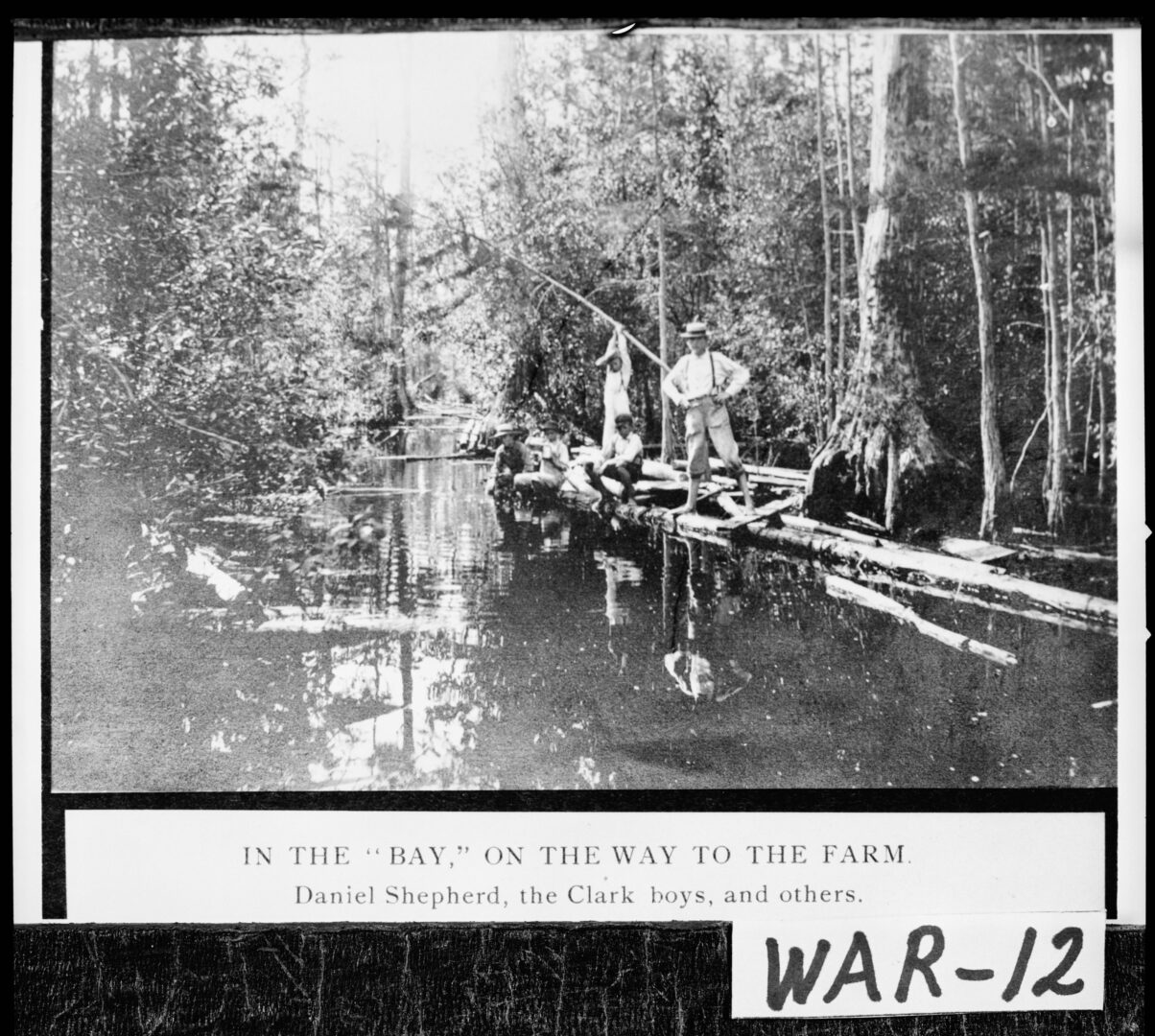

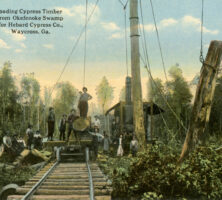

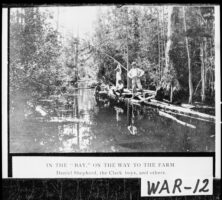

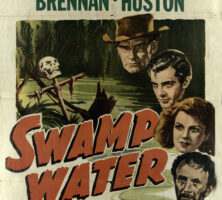

Called the “land of trembling earth” by early Native Americans, the Okefenokee Swamp is perhaps most famous for successfully resisting all attempts to subdue and exploit it. Occupying 700 square miles in southeastern Georgia, it was drained by timber companies and dredged for canal construction, and its wildlife was hunted to near extinction. Yet this primitive swamp remains intact, translating a reputation for danger and mystery into a popular attraction.

In the 1920s conservation groups like the Okefenokee Society and the Georgia Society of Naturalists began advocating for the protection of the swamp and its wildlife. Feature articles about the area published in National Geographic and Natural History in the 1930s drew national attention and appreciation for its rugged beauty. When plans emerged in the 1920s and 1930s for the construction of canals and roadways that would have destroyed the swamp, public outcry forced government intervention. In 1937 U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge on land purchased from the Hebard Cypress Company.

Although prominent in adventure novels and essays as early as the 1870s, the swamp did not develop as a tourist destination until the 1940s. With the approval of Georgia governor Ellis Arnall and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Okefenokee Association leased 1,200 acres to create the Okefenokee Swamp Park, which opened in 1946. Since the 1950s, local sightseeing companies have capitalized on the allure of the swamp by leading tours into the untamed interior filled with alligators and bears. Today, the area has three public access entrances that enable visitors to fish, kayak, observe wildlife, and learn about the local environment. The continued appeal of this “grand old man of swamps” remains undeniable.

Helen: An Alpine Invention

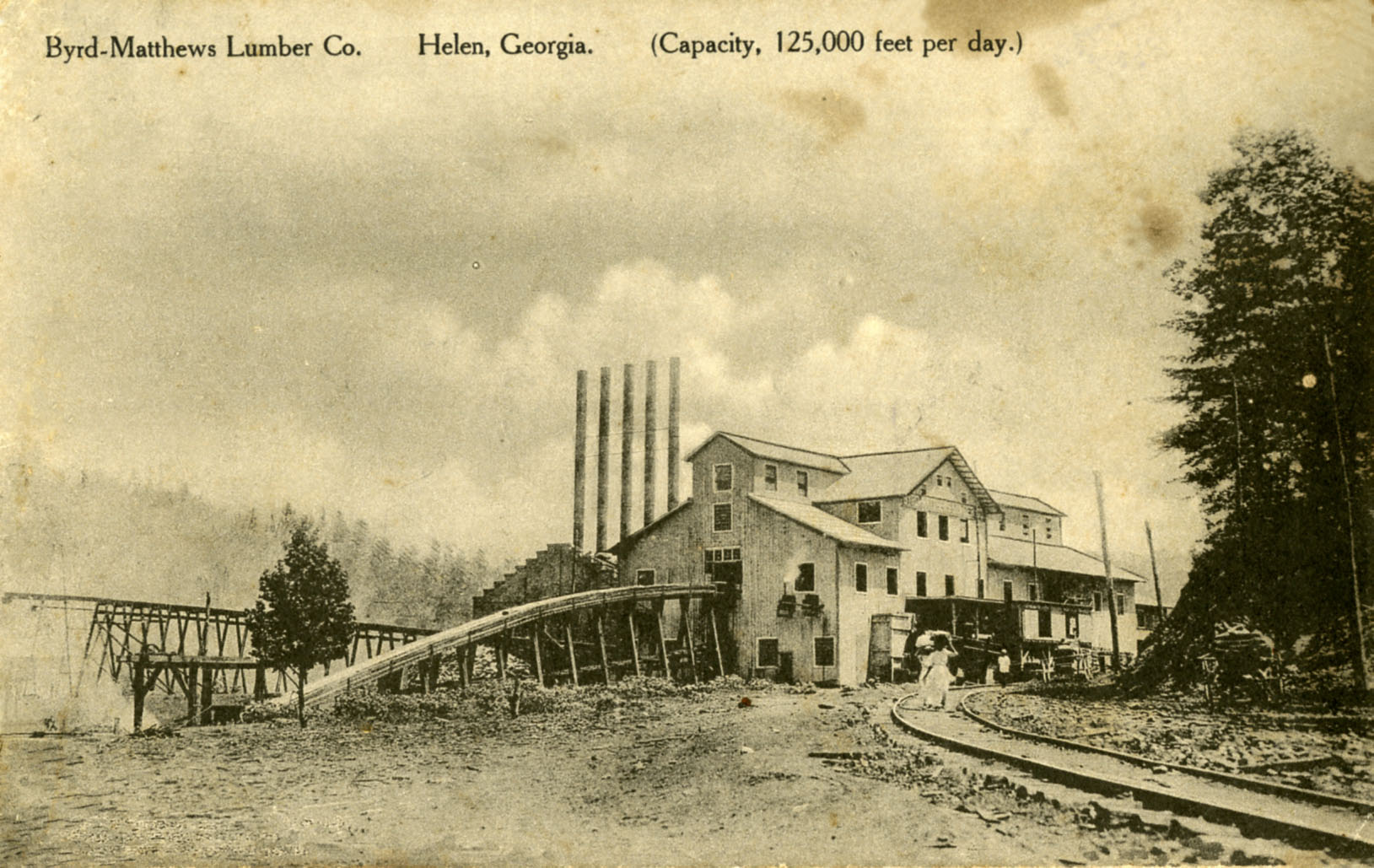

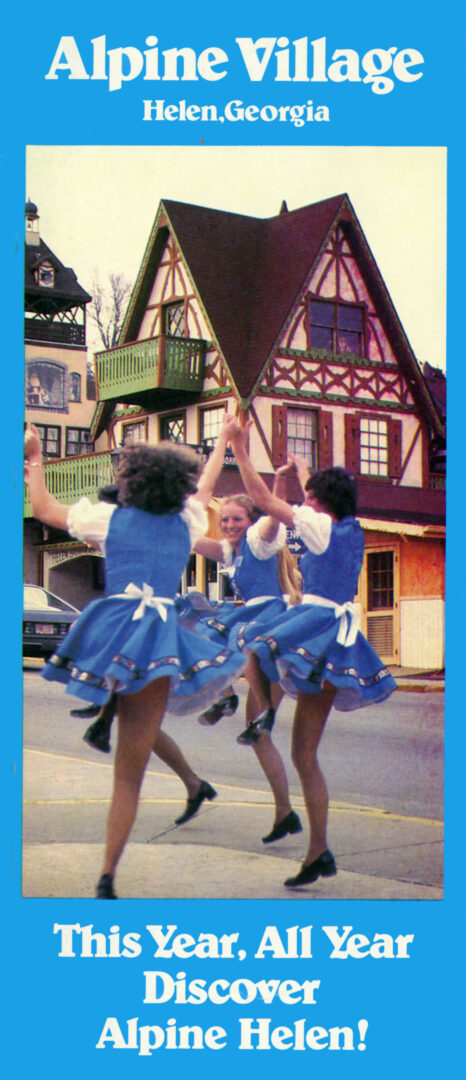

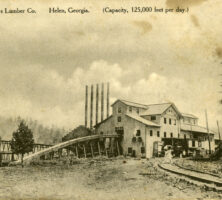

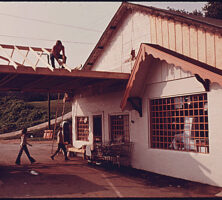

Helen once thrived as a logging and mining town, but by the late 1920s the lumber industry had decimated local resources and moved on. Without logging traffic, the 1.5-mile rail line into Helen shut down in 1928. In the decades that followed locals looked for new ways to attract visitors to the area, with limited success. In 1968, after years of dwindling population numbers and economic prospects, local businessmen Bob Fowler, Pete Hodkinson, and Jim Wilkins met to discuss ways to revitalize the business district. They approached local artist John Kollock, who suggested that the town capitalize on the beauty of the surrounding mountains by transforming itself into a Bavarian-themed village. Business owners agreed, and soon thereafter the idea was approved by the mayor and city council.

Helen was reborn in April 1969 with a new charter that granted the city control over the exterior appearance of buildings downtown. By the early 1970s, the European ambiance was taking shape, and visitors inundated the town, celebrating Oktoberfest and enjoying festivals in a newly quaint “German” village. Despite the popularity of Helen’s new façade, many critics bemoaned the town’s campy commercialization and divorce from the region’s Appalachian history. Nevertheless, Helen’s transformation highlights a successful alliance between local businessmen and civic leaders to revive a sleepy Georgia village. In 2003 Helen was the third most popular tourist destination in Georgia, behind Atlanta and Savannah.

Stone Mountain: A Complex Attraction

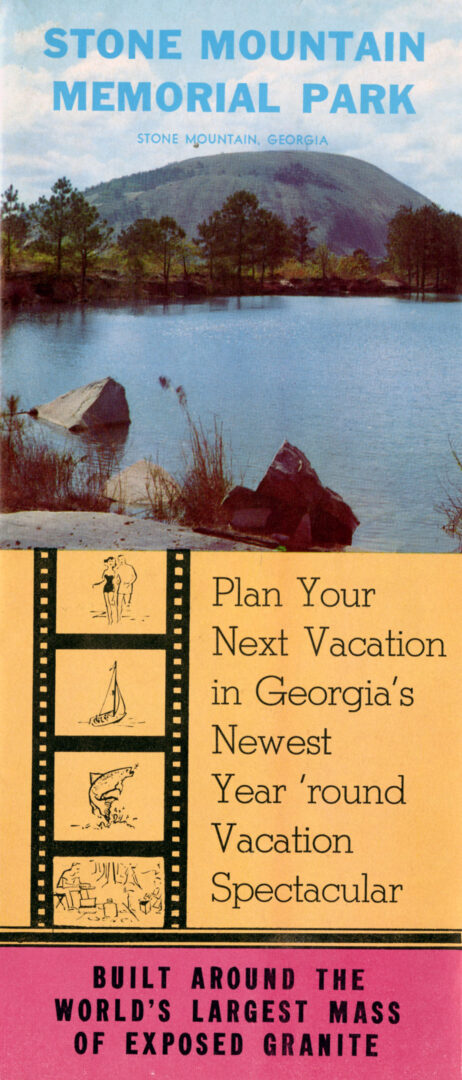

Since the 1850s, people have come to marvel at the world’s largest mass of exposed granite at Stone Mountain. In 1914, at the height of Civil War (1861-65) memorial construction in the South, the United Daughters of the Confederacy proposed a monument for the site. The Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association hired renowned sculptor Gutzon Borglum, creator of Mount Rushmore in South Dakota, to construct a carving of revered Confederate figures Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Following ongoing disagreements, Borglum left the project in the 1920s, with the carving incomplete.

The civil rights movement revived attention in the unfinished monument among pro-segregationists. In 1958 Georgia governor Marvin Griffin led efforts to establish the Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA), which purchased the property and oversaw the development of Stone Mountain Memorial Park. The completed carving was dedicated in 1970.

Since the 1970s Stone Mountain has attempted to move beyond promoting a romanticized and largely conflict-free vision of the Old South. Although the Confederate carving remains prominent, and an interpreted antebellum plantation is among the featured attractions at the site, developers have focused on appealing to a culturally diverse audience. In 1998 Herschend Family Entertainment began operating Stone Mountain as a joint venture with the state. This public-private partnership today administers a family-friendly theme park, attracting 4 million visitors annually and offering a host of attractions, including a laser light show, sky lift, and scenic railroad, in addition to hiking trails, a golf course, and fishing and picnicking areas. Though not without controversy, today’s modern site offers tourists experiences beyond just Confederate memory.