Episcopalians are American members of the Christian denomination known broadly as Anglican, and the Episcopal Church is a member of the worldwide Anglican Communion.

Before the American Revolution (1775-83) members of the Anglican Church, or Church of England, composed the largest and most influential religious group in Georgia, having been instrumental in the founding of the colony. In 1789 American Anglicans, including those in Georgia, formally reconstituted themselves as the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. As of 2003, the state’s 165 Episcopal congregations were divided into two administrative sections, known as dioceses, with a total of 72,637 baptized members.

Revolutionary and Antebellum Years

Despite their strength prior to the American Revolution, Georgia’s Episcopalians struggled during and after the war. Understandably, the former members of the official British denomination were divided on many issues, ranging from attitudes about the war itself to elements of liturgical expression in their revised prayer book. When British authorities were expelled from the colony after the war, Georgians scrabbled to find clergy. They also had to battle non-Episcopalians’ lingering suspicions of the group’s loyalty to England. These factors ledto a period of dormancy for all of Georgia’s Episcopal congregations except for Christ Church in Savannah, the oldest and largest congregation in Georgia.

In the rest of the state a small number of determined Episcopalians worked steadily to rebuild their membership, and by 1823 there were three parish churches: Christ Church, Savannah; Christ Church, St. Simons Island; and St. Paul’s Church, Augusta. These churches formed the first diocese in the state, which gave them voting rights at the national church’s general convention. Initially, the young diocese did not have enough members to qualify for its own bishop, but steady growth allowed for a bishop by 1841. To the three original parishes were added Christ Church, Macon; Trinity Church, Columbus; and Grace Church, Clarkesville. Also added were a number of missions, or congregations supported at the diocesan level, whose members hoped to achieve parish status. It is estimated that the state’s Episcopalians numbered about 300 by 1840.

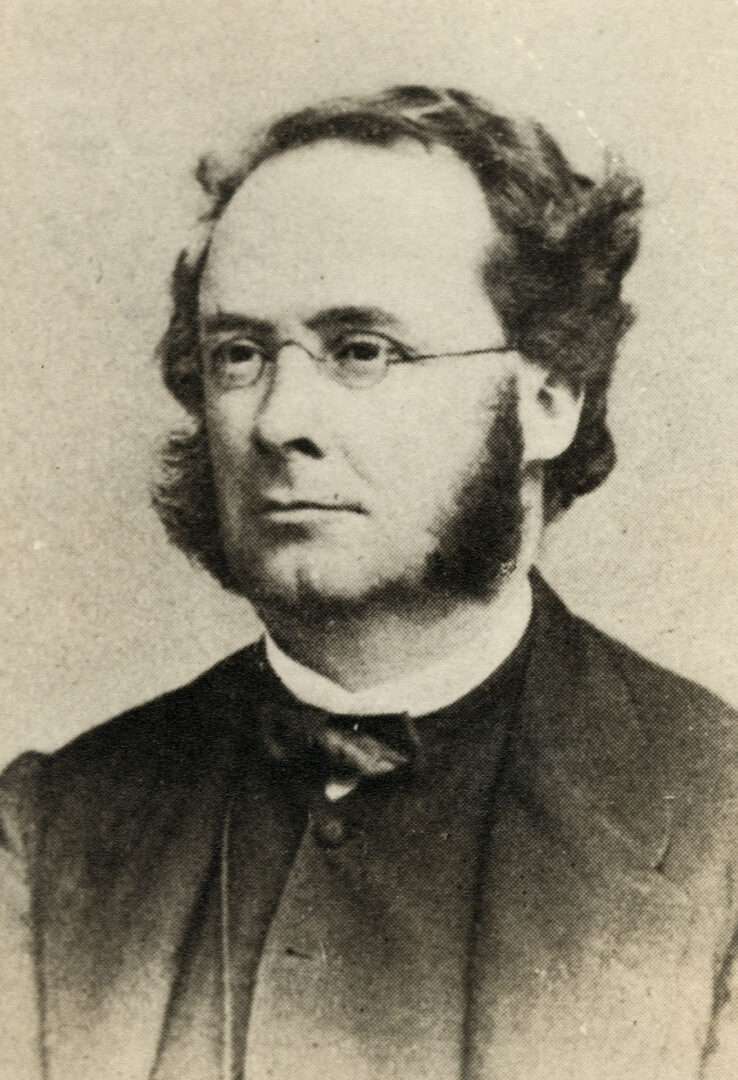

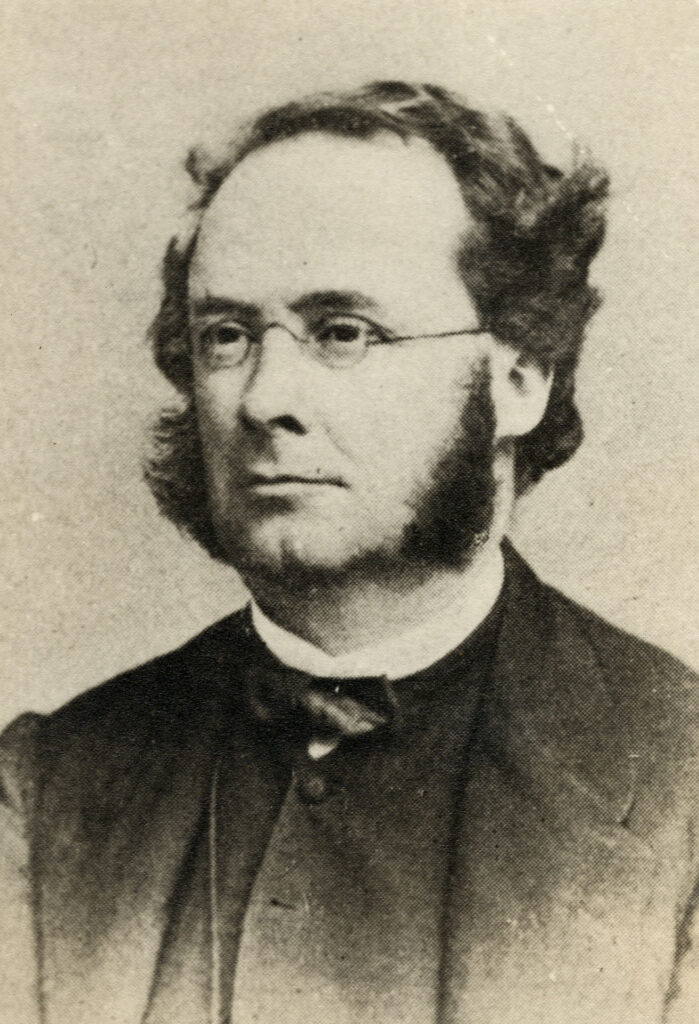

The first bishop in Georgia was Stephen Elliott Jr., a South Carolina native. Educated at Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts, he had been a member of the Charleston bar before studying for the priesthood. Elliott’s peers, recognizing his talents, elevated him to the episcopate in 1841, just five years after his ordination. As bishop, Elliott founded missions and new parishes across the state. He also founded a number of schools for the religious education of enslaved children. Twenty years after he took office, the Episcopal Church in Georgia had grown from 6 to 28 parishes and from 300 to 2,000 communicants, becoming the fifth-largest denomination in the state.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Elliott continued to serve as the Civil War (1861-65) loomed. With secession, Episcopal leaders in Georgia joined with other southern Episcopal leaders to form the separate Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America. Elliott accepted its members’ request to provide leadership for this new body. Its first formal convention, the First General Council, was held in November 1862 in St. Paul’s Church in Augusta. Soon afterward the bishops of several southern dioceses sent out a pastoral letter stressing that only political, not doctrinal, differences called for their withdrawal from affiliation with the Union’s Episcopalians. Their parishioners supported the Confederacy in numerous ways, including sending their sons into battle and housing troops in church buildings. Although clergy were exempt from conscription, a number of them joined their parishioners in active service.

Although he had led his colleagues and their congregations to form the Episcopal Church in the Confederacy, Elliott was just as active in persuading them to dissolve the organization after the war. This was accomplished formally in November 1865 at the Second General Council in Augusta, and as a result the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States welcomed the southern dioceses back.

The Civil War depleted the churches of numerous young men and, along with a subsequent national depression in 1870, severely reduced their fiscal resources. Despite these difficulties, leaders of the church in Georgia held to their humanitarian beliefs during Reconstruction. Survivors in many congregations formed guilds to help the unemployed find jobs and to provide charity for those unable to work, and they sometimes diverted donations from outside the South for the rebuilding of churches to the care of war orphans.

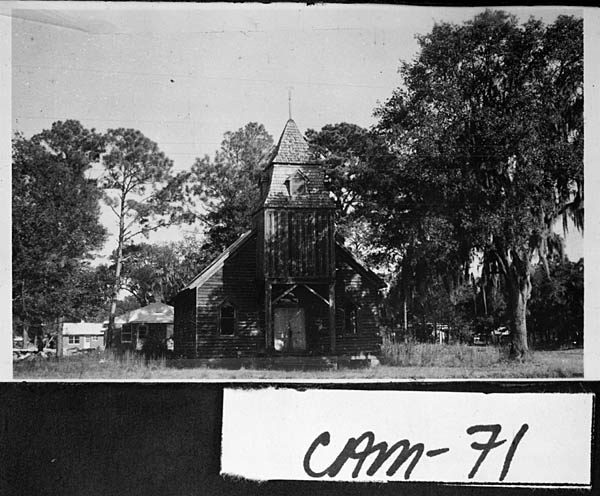

Following emancipation, the numbers of Black Episcopalians grew in Georgia, eventually becoming large enough to populate several churches. In addition to gathering in a number of mission churches, some Black communities were financially able to support their own operations, thus forming parish churches. The first of these, St. Stephen’s Church (later St. Matthew’s), was established in Savannah in 1855, followed by St. Athanasius Church, established in Brunswick around 1874. By 1910 the Diocese of Georgia formed the Council of Colored Churchmen to represent its African American congregations, which effectively kept Black and white church leaders from working together for several decades.

Elliott died suddenly in 1866. His successor, John Watrous Beckwith, continued to urge Georgia’s Episcopalians to provide formerly enslaved people with religious training and other help. Mission churches for the freedmen and-women were supported by established congregations around the state, and the Episcopal Commission of Home Missions to Colored People opened schools (both for religious and industrial training), in addition to supporting a number of Black clergymen in the South. Beckwith’s death in 1890 left the state’s Episcopalians without someone to perform crucial ceremonies. In 1892, after a difficult search, the diocese found its third bishop, Cleland Kinloch Nelson.

Twentieth Century

In 1907, during Nelson’s tenure, a burgeoning population necessitated the division of the Diocese of Georgia. The new Diocese of Atlanta comprised the northern and middle parts of the state, and its bishop was seated, or based, in Atlanta. Nelson chose to lead the new diocese. Lauded for his successful supervision of the division, Nelson is also remembered for his outspoken opinions in the name of justice. He spoke out against the 1915 lynching of Leo Frank, chiding his flock for their “disregard of justice and indifference to the value of human life.” Nelson died in 1917, the same year that the United States entered World War I.

Following the creation of the Diocese of Atlanta, the Diocese of Georgia, seated in Savannah, selected Frederick Focke Reese as bishop. He served from 1908 until his death in 1936. Inheriting as his charge a large sector of the less-prosperous agricultural parts of the state, Reese was nevertheless a capable leader through World War I and the first years of the Great Depression.

The number of Episcopalians in Georgia increased during World War I, although fewer numbers of priests were available to congregations during the conflict. Parishes, however, responded generously to calls for financial assistance to support the efforts of their internal missions. Henry Judah Mikell, Nelson’s successor in Atlanta, emphasized the need for the Episcopal Church to work with the state’s college students, as well as to continue its work among African Americans. Under his leadership the diocese established college centers, which ministered to students at universities and colleges around Georgia. In 1933, as part of his efforts to help young people affected by the depression, Mikell founded “Camp Mikell” at Toccoa Falls. Relocated in 1941 to another site outside of Toccoa, the Mikell Camp and Conference Center continues to support meetings, classes, contemplative retreats, and recreational gatherings for Episcopalians of all ages. The Diocese of Georgia maintains a similar center, the Georgia Episcopal Camp and Conference Center (or Honey Creek), which is located near Waverly in southeast Georgia.

The Great Depression of the 1930s affected both of the state’s dioceses. The leadership and congregants found it difficult to pay salaries, so they cut expenses by reducing or eliminating support for some of their publications and schools. However, they managed to fund a celebration, consisting of ceremonies and special services, in 1933 to commemorate the bicentennial of the Anglican Church’s founding in Georgia. World War II (1941-45) brought challenges similar to the ones seen during previous conflicts—the financial resources of the churches were diverted to the war effort, and many of the congregations’ young men were called to military service.

Integration and Dissension

The 1950s and 1960s were a time of prosperity as well as civic unrest. With the arrival of the civil rights movement, Episcopalians in Georgia struggled with the same racial issues as did the larger southern society. The Council of Colored Churchmen, formed early in the twentieth century, was disbanded in 1947, when the rector of Savannah’s Christ Church, Francis Bland Tucker, began a push to desegregate the Episcopal Church in Georgia. During the civil rights movement, Tucker was instrumental in leading Christ Church (and thus many of its sister congregations) into a peaceful acceptance of integration by exhorting his congregation “not to pass any resolution or take any action that would prevent the entry of any person into the house of God.”

During the 1960s the Episcopal Church on the national level became more active in political causes, especially in the case of the Vietnam War (1964-73). This activity, as well as changes made in 1979 to the denomination’s prayer book and accompanying rituals, the first such changes since 1928, brought dissension and led some congregations, including some in Georgia, to leave the majority and form independent churches.

African American Bishops

Between 1874 and 1989, four of the Episcopal Church’s African American bishops were born in Georgia. The first was Henry Bard Delaney, born in St. Marys in 1858. From 1918 until his death in 1928, he served as Suffragan Bishop for Colored Work in the Diocese of North Carolina. A second African American bishop from Georgia was Dillard Houston Brown, born in 1912 in Marietta. He was consecrated Bishop Coadjutor of Liberia in 1961 and was assassinated in 1969. John Thomas Walker was the third Black Episcopal bishop from Georgia. Born in Barnesville in 1925, he was consecrated Bishop of Washington in 1977. The fourth African American bishop was Quintin Ebenezer Primo Jr., born in Liberty County in 1918. After serving as Suffragan Bishop of Chicago from 1972 until 1985, he became Interim Bishop of Delaware.

Twenty-first Century

As of 2003 the Diocese of Atlanta consisted of 93 congregations throughout north Georgia with 54,006 baptized members. The bishop of the diocese is seated at the Cathedral of St. Philip in Atlanta, one of the largest congregations in the denomination, with more than 5,000 members. In 2012 Bishop Robert C. Wright was elected as the Diocese of Atlanta’s tenth bishop. He is the state’s first Black Episcopal bishop. In addition to reaching out to the region’s growing Hispanic population, members of the Atlanta diocese have joined with Muslim community members to assist refugees settling in the metropolitan area.

The southern part of the state continues under the Diocese of Georgia, with the seat of administration located in Savannah. Bishop Scott A. Benhase, the former rector of St. Alban’s Parish in Washington D.C., was consecrated as the diocese bishop in 2010. As of 2007 it consisted of 71 congregations with 18,651 baptized members.