The Chattahoochee River rises high in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Georgia and flows southwesterly toward the Alabama state line. From there the river tumbles for twenty miles over the fall line—the region of transition between the foothills of the Piedmont and the lower and flatter Coastal Plain. Below the fall line in Columbus, the river slows to ramble south toward Florida, where it is known as the Apalachicola.

Early History

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans have lived along the banks of the Chattahoochee River for a very long time. Dating to 1000 B.C., the Kolomoki complex near present-day Blakely is one of the best-known sites of these ancient civilizations. During the Mississippian Period (A.D. 800-1600), at least sixteen significant settlements dotted the Chattahoochee’s banks south of the fall line. As these civilizations died because of exposure to European diseases, native survivors from other areas moved into the river valley below present-day Atlanta. They arrived separately and at different times but eventually established sufficient political, linguistic, and cultural bonds to be referred to as one people—the Creeks. (The Cherokees lived near the headwaters of the river.) The Creeks may have acquired their English name from their habit of settling near the larger tributaries of rivers like the Chattahoochee. The Creeks respected the river as a food source, a transportation artery, and an esteemed element of the spirit world. The Creeks named the river; Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins recorded in 1799 that chat-to meant “stone,” and ho-che meant “marked” or “flowered.”

From Flowing through Time: A History of the Lower Chattahoochee River, by L. Willoughby

By treaty, the Creeks gradually ceded their lands to white settlers south of Fort Gaines in 1814 and east of the Chattahoochee by 1825. In 1827 the Florida legislature established the port town of Apalachicola and built wharves to receive upstream cotton. In 1828 the Georgia legislature created the town of Columbus at the head of navigation.

River Traffic and Trade

The first steamboat to run from the Gulf of Mexico to Columbus was the Fanny, which completed the journey of several months in January 1828. Other boats quickly followed, and Columbus became a thriving cotton-marketing center with unimpeded river travel to the south and intermittent river travel possible northward all the way to present-day Gwinnett County in metropolitan Atlanta.

Most of the year, however, the twenty miles of waterfalls along the fall line between Columbus and Franklin acted as a barrier separating the two navigable ends of the Chattahoochee. Above the falls, Colonel Reuben Thornton ran barges and flatboats from West Point to Standing Peachtree, about sixty miles upstream and seven miles from present-day Atlanta’s Five Points area. Others ran flatboats between Franklin and West Point as early as 1838. The various settlements in the present-day Atlanta area grew up around taverns at ferries that allowed travelers to cross the river and continue on into Tennessee by land. Northeast of present-day Atlanta the Chattahoochee River resembled a swift creek and powered a number of sawmills and gristmills.

Civil War and Postwar Development

By the late 1830s the towns located at the fall line along the Chattahoochee also used the river as an industrial power source for textile mills and gristmills. By the time the Civil War began in 1861, Columbus was known as “the Lowell of the South,” after the home of industrial revolution, Lowell, Massachusetts. Its mills were vitally important to the Confederacy, and defense of the river was crucial, because it represented the easiest route to the fall line mills from the Gulf of Mexico, especially after Union naval forces took possession of Apalachicola in April 1862.

Courtesy of Edwin L. Jackson

The Confederate government created the Chattahoochee-Flint-Apalachicola military district, commanded by General Howell Cobb, in November 1862. Cobb directed the obstruction of the river, which was effective in keeping out the enemy by water. However, Union land forces did invade the river valley in 1864, when General William T. Sherman’s army crossed over the Chattahoochee just north of Atlanta and sacked the city before moving on toward Savannah in the March to the Sea. As the war was ending in April 1865, General James H. Wilson’s forces crossed the Chattahoochee River to destroy the factories and mills of Columbus and West Point.

The golden age of steamboating on the Chattahoochee dawned once the area recovered from the war’s destruction. Opulent new passenger boats replaced the workhorse freighters of the antebellum period. Innovations in service made river travel more reliable, and technological breakthroughs made it safer. Freight became more diversified, with lumber products, fertilizer, and honey crowding the ubiquitous cotton bales. During this period poet Sidney Lanier composed “The Song of the Chattahoochee” (1877), in which the river narrates its journey through Habersham and Hall counties.

Instead of calling on every homestead or business along the river, by 1900 steamboats stopped at only twenty-eight major communities or railroad junctions. Sixteen years later, the steamers made only five stops as the river trade shifted to the lower river (south of Eufaula, Alabama), where navigation was unimpeded by seasonal low water and natural obstructions.

Power, Dams, and Controls

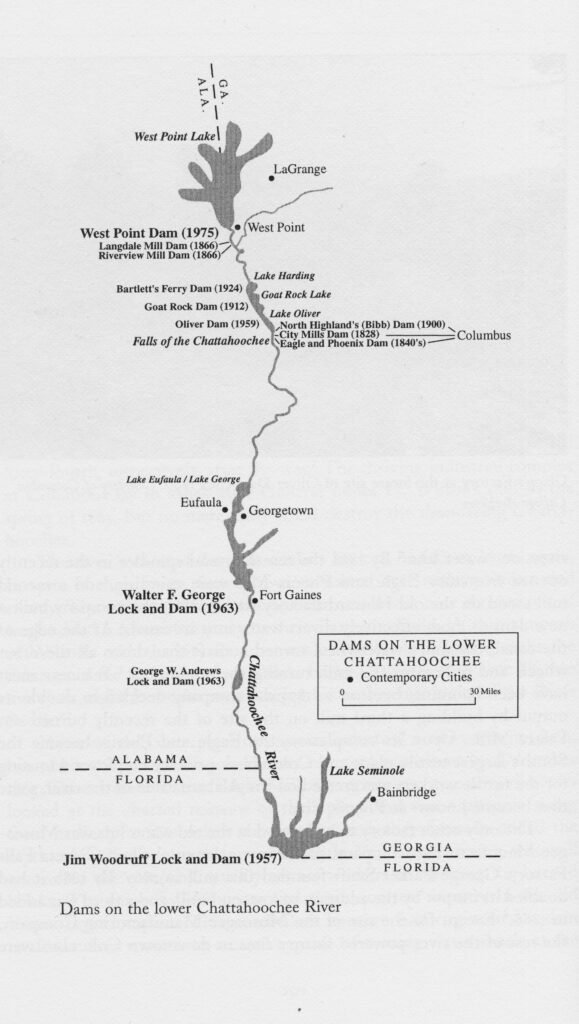

In the post–World War I era, rail lines and improved roads proved to be the most direct and dependable form of transportation. The river was relied on less as a transportation conduit than as a hydroelectric power provider. Using the rushing water of the fall line, citizens built the first large-scale hydroelectric dams between 1899 and 1924 at North Highlands, Goat Rock, and Bartlett’s Ferry. After these early modern dams were in place, the public began to see the need for other dams for flood control. At West Point especially, residents were so accustomed to high waters that the town raised the wooden sidewalks five feet above street level.

In 1953 Congress authorized the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint Project, which set out to construct four dams for flood control, power generation, and navigation. The Jim Woodruff Dam (backing up the waters of the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers to create Lake Seminole); the George W. Andrews Lock and Dam at Columbia, Alabama; the Walter F. George Lock and Dam near Eufaula, Alabama; and the Buford Dam near Gainesville were all completed by 1963. The Georgia Power Company built a final hydroelectric dam, known as Oliver Dam, near Columbus in 1959. After a particularly devastating flood in 1961, Congress finally authorized a dam for West Point in 1962, which was completed in 1975.

Today the Chattahoochee River is valued more as a source of drinking water and recreation than as a transportation artery. The water it supplies underpins the regional economies of today and tomorrow. While Georgia, Alabama, and Florida squabble over the unrestricted right to use the river, the Chattahoochee continues to follow its ancient route to the sea. Though it is used little as a highway today, it remains the valley’s most important ecological and economic asset.