Among the numerous New Deal programs of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) is remembered as one of the most popular and effective. Established on March 31, 1933, the corps’s objective was to recruit unemployed young men (and later, out-of-work veterans) for forestry, erosion control, flood prevention, and parks development. The president’s ambitious goal was to enroll a quarter of a million men by July 1, 1933. In what is considered to be a miracle of cooperation, four government agencies collaborated to turn Roosevelt’s goal into reality.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

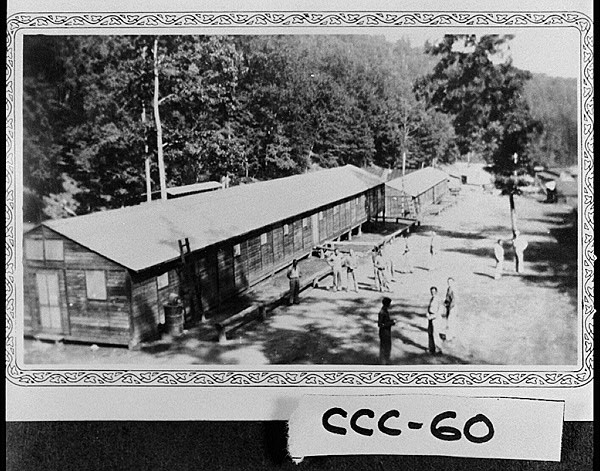

The U.S. Department of Labor recruited men for six-month enlistments; the U.S. Department of War provided army officers to operate 200-man work camps; and the U.S. Departments of Interior and Agriculture identified projects and supervised the work (local experienced men, called “LEMs,” were also employed to train and oversee the mostly unskilled laborers). By the president’s deadline, 274,375 men were at work in 1,300 camps nationwide. During the CCC’s nine-year existence, more than 3 million men, endearingly called “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” worked from 16,000 camps carrying out projects across the nation.

To manage this complex organization, President Roosevelt tapped Robert Fechner, the vice president of the International Association of Machinists. Raised in Macon and Griffin, and trained as a machinist in Augusta, Fechner proved to be an exceptional choice for the job, working tirelessly on behalf of the program and the men until his death in 1939.

Georgia’s Tree Army

Despite opposition from Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge, who argued that federal New Deal programs were an intrusion into state government affairs, the CCC was overwhelmingly popular in Georgia. Before the corps’ termination on July 1, 1942, more than 78,000 men were employed in 127 camps (approximately 30-35 camps operated at a time) across the state.

Enrollment in the CCC was determined by quota based on state population and unemployment rolls. By law, racial discrimination was prohibited. Nonetheless, nearly all the camps were segregated, and African Americans were often discouraged or even prevented from enlisting. Early in the program, several southern states, including Georgia, failed to recruit eligible Black workers until the Labor Department threatened to withhold a state’s entire quota unless the issue was satisfactorily addressed.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

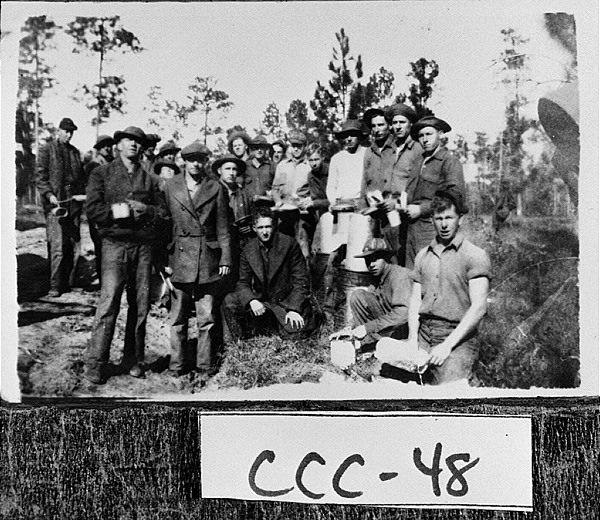

The CCC’s motto was “We Can Take It!,” and camp life was a mixture of hard work and camaraderie. Enrollees from city streets and rural farms learned to live, work, and play together. Men acquired skills that, for many, led to careers or prepared them for service in World War II (1941-45), and the $30 per month they earned ($25 went home to families) helped loved ones survive the dark days of the Great Depression. The men of Company 4463 GA SP-13, who developed a state park on Pine Mountain, even had the distinction of serving as President Roosevelt’s honor guard during his visits to nearby Warm Springs for polio therapy.

An Enduring Legacy

Across the state, the CCC carried out projects of lasting value to all Georgians. Enrollees planted more than 22 million trees, constructed nearly a half-million erosion-control dams, and ran more than 3,600 miles of telephone lines. Perhaps their most tangible legacy is found in Georgia’s state parks, national parks, and national forest.

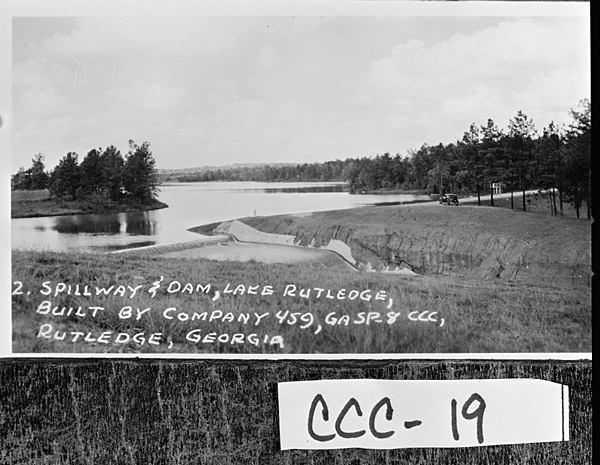

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

In 1933 Georgia had two “state forest parks” at Indian Springs, in Butts County, and Vogel, in Union County. With support from the National Park Service, six more state parks were established over the next nine years. CCC workers built lakes and ponds, constructed cabins and lodges of now characteristic “park rustic” design, blazed trails, and in collaboration with the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, erected group camps at selected parks, then known as “Recreational Demonstration Areas.” Today, visitors still enjoy CCC craftsmanship at the parks mentioned above, as well as at A. H. Stephens (Taliaferro County), F. D. Roosevelt (Harris County), Fort Mountain (Murray County), Hard Labor Creek (Morgan County), Kolomoki Mounds (Early County), and Little Ocmulgee (Telfair County and Wheeler County) state parks.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

CCC work in Georgia’s national park properties focused on the preservation of natural or historic features. At Chickamauga and Kennesaw Mountain battlefields, in Walker and Cobb counties respectively, preservation included the construction of roads and trails, and restoration of historic fortifications. At the Ocmulgee mounds, outside of Macon, enrollees supported archaeological work and building construction. They carried out road and bridge work at Andersonville National Historic Site, in Macon County, and restored the masonry walls and dikes at Fort Pulaski National Monument, located just outside Savannah.

While CCC work in the Chattahoochee National Forest (created from the Cherokee National Forest in 1936) in north Georgia focused on reforestation, insect control, and fire prevention, CCC men also constructed campgrounds and recreation areas that remain popular today at the Pocket, Lake Conasauga, and Lake Winfield Scott.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

The CCC also worked on numerous other projects around the state. Workers helped construct the Appalachian Trail in Georgia and built the oldest shelter at Blood Mountain, and they cleared land and built fire towers and roads at Fort Stewart. An all-Black unit developed facilities at the Okefenokee Swamp Wildlife Refuge.

At Vogel State Park a small museum, the John B. Derden CCC Museum, contains artifacts and photographs of the men.

A poem written by an anonymous CCC enrollee sums up the enduring value of their labors: “All over this country, the work we did with our hands, our minds, and our bodies, still stands today as a monument. . . . We put our mark on this land and that mark will be seen for many years to come.”