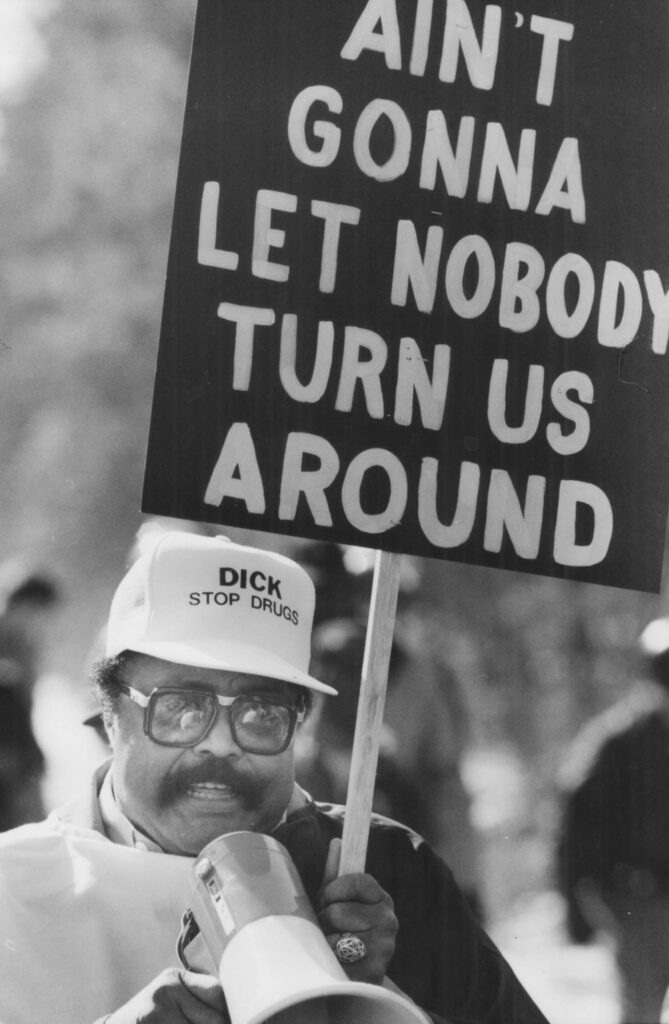

Hosea Williams, a former aide to Martin Luther King Jr., was a principal leader of the civil rights movement. Renowned for his militancy and his ability to organize demonstrations and mobilize protesters, he was arrested more than 125 times. Williams helped coordinate the 1965 protest march in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery, served as pastor of King’s People’s Church of Love, and was executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

He also took on more traditional governmental roles: he served in the Georgia General Assembly from 1974 to 1985, on the Atlanta City Council from 1985 to 1990, and as a DeKalb County commissioner from 1990 to 1994.

Early Life and Education

Hosea Lorenzo Williams was born on January 5, 1926, in Attapulgus, in Decatur County. His teenage parents were unmarried. They were also blind and had been committed to a trade institute for the blind in Macon. Because his mother ran away from the institute upon learning of her pregnancy, Williams never knew his father. His mother died while giving birth to her second child, and Williams was raised in Attapulgus by his maternal grandparents, Lela and Turner Williams. Nearly lynched because of his alleged involvement with a white girl, Williams left home at the age of fourteen. He held menial jobs for several years until he enlisted in the U.S. Army at the outset of World War II (1941-45) and served in an all-Black unit attached to General George Patton’s Third Army. Severely wounded in battle, which earned him a Purple Heart and left him with a permanent limp, Williams spent a year in a military hospital in Europe.

Upon his return to Georgia and civilian life, Williams completed the requirements for a high school diploma at the age of twenty-three. He enrolled at Morris Brown College in Atlanta, with the aid of the G.I. Bill, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. After completing a master’s degree in chemistry from Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), Williams became a chemist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Savannah, and in the the early 1950s he married Juanita Terry. In 1976 he founded the Southeast Chemical Manufacturing and Distributing Company, which specialized in cleaning supplies. Over the years Williams founded three more chemical companies and a bonding company.

Civil Rights Involvement

In the 1950s and early 1960s Williams encountered his share of intense racism. He spent five weeks in the hospital after being beaten for drinking from a “whites only” water fountain at a bus station in Americus, and he was fired from the Department of Agriculture in 1963 for speaking out against racist policies (he was reinstated through an appeals process but resigned later that year).

The father of nine children, Williams devoted himself fully to the cause of civil rights in the early 1960s after some of his children were refused sodas at a segregated lunch counter in Savannah. He joined the Savannah chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and served as vice president under W. W. Law. Williams led marches and sit-ins to protest segregation. As a result of his efforts, Savannah was the first city in Georgia with desegregated lunch counters. He also helped to integrate the Nancy Hanks, the South’s first passenger train, and the public beach on Tybee Island. In 1962 King acknowledged Williams’s role in making Savannah the most integrated city in the South. Williams resigned from the NAACP that same year, after learning that his candidacy for the national board of directors had been rejected.

In the summer of 1961 Williams took part in the campaign to register voters, and in 1963 he led protests by the Chatham County Crusade for Voters. He was arrested after several white citizens swore out peace warrants against him. Williams was jailed for sixty-five days, the longest continuous sentence served by any of the civil rights leaders. During the riots that followed his arrest, the Sears and Firestone stores in Savannah were burned. Led by Mills B. Lane Jr., president of Citizens and Southern Bank, prominent white Savannahians, fearing for their city, formed a “Committee of 100” to secure Williams’s release and to work on completing the desegregation of the city.

The King Years and SCLC Leadership

It was also in 1963 that Williams joined the SCLC at the urging of King, the organization’s president. Two years later King asked Williams and John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to lead a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state’s capital, Montgomery. The goal of the march was to peacefully deliver to Alabama governor George C. Wallace a petition for African American voting rights. The protest on March 7, 1965, became known as “Bloody Sunday” after several hundred marchers, including Lewis and Williams, were beaten with clubs and whips and fired upon with tear gas while crossing Selma’s Edmund Pettis Bridge. After watching national television coverage of the incident, U.S. president Lyndon Johnson forced the Voting Rights Act through Congress in August 1965. Williams continued his close association and friendship with King and was at his side when King was assassinated in April 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee.

Williams held several positions within the SCLC. He was special projects director from 1963 to 1970, national program director from 1967 to 1969, and regional vice president from 1970 to 1971. He also served as national executive director from 1969 to 1971 and again from 1977 to 1979, when he was removed by then-president Joseph Lowery, who accused Williams of not devoting his full attention to the position.

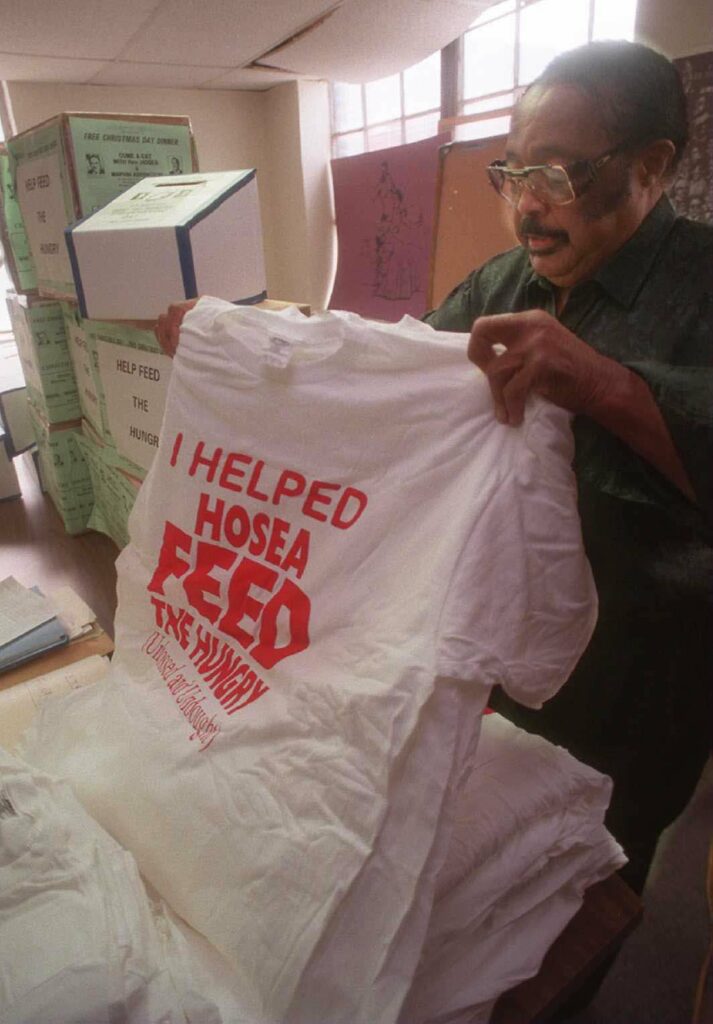

In 1971, while he was still serving the SCLC, Williams founded in Atlanta the Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless program, which he ran for thirty years. The program continues under the direction of his daughter, Elizabeth Williams Omilami, and provides thousands of people with food, medical attention, and clothing. In 1984 he founded the annual Sweet Auburn Heritage Festival to celebrate and revitalize the Sweet Auburn historic district.

Atlanta Politics

In 1968 Williams entered the political arena. That year he ran unsuccessfully for the Georgia House of Representatives. He switched to the Republican Party and lost the race for the secretary of state’s office in 1970. Returning to the Democratic Party, he lost the U.S. Senate primary in 1972 and the Atlanta mayoral primary the following year. But Williams’s persistence paid off, and in 1974 he was elected as a Democratic senator to the state senate, where he served until 1985, when he resigned to run again for the U.S. Senate. Williams lost to Wyche Fowler but was elected the same year to the Atlanta City Council, on which he served for five years. Williams lost the 1989 mayor’s race to Maynard Jackson and was subsequently elected to the DeKalb County Commission, where he served until 1994. Juanita Williams, Hosea’s wife, was elected to fill her husband’s former seat in the Georgia legislature. An activist, educator, and writer, she served four terms; she was the first Black woman to run for public office in Georgia since Reconstruction, and the first Black woman to run for statewide office.

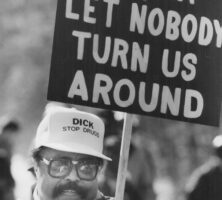

In 1987 Williams received international attention when he led two marches in majority-white Forsyth County to confront the Ku Klux Klan. The Brotherhood March was planned to honor Martin Luther King Jr. on the observance of the national King holiday. During the first march on January 17, Williams and 75 supporters were confronted by 400-500 Klan members and sympathizers who broke through police lines throwing rocks and bottles. Public outrage was such that on the following weekend, Williams led 20,000 marchers, including Coretta Scott King, Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, Colorado senator Gary Hart, and activist Jesse Jackson, protected by more than 2,000 National Guardsmen and police, in what became the state’s largest civil rights demonstration. Williams gave Forsyth County a list of demands that included fair employment, the return of property lost when Blacks were expelled from the county by the Klan in 1912, and a biracial council. A jury later awarded $950,000 to the marchers in a class action suit filed by Williams against the Klan.

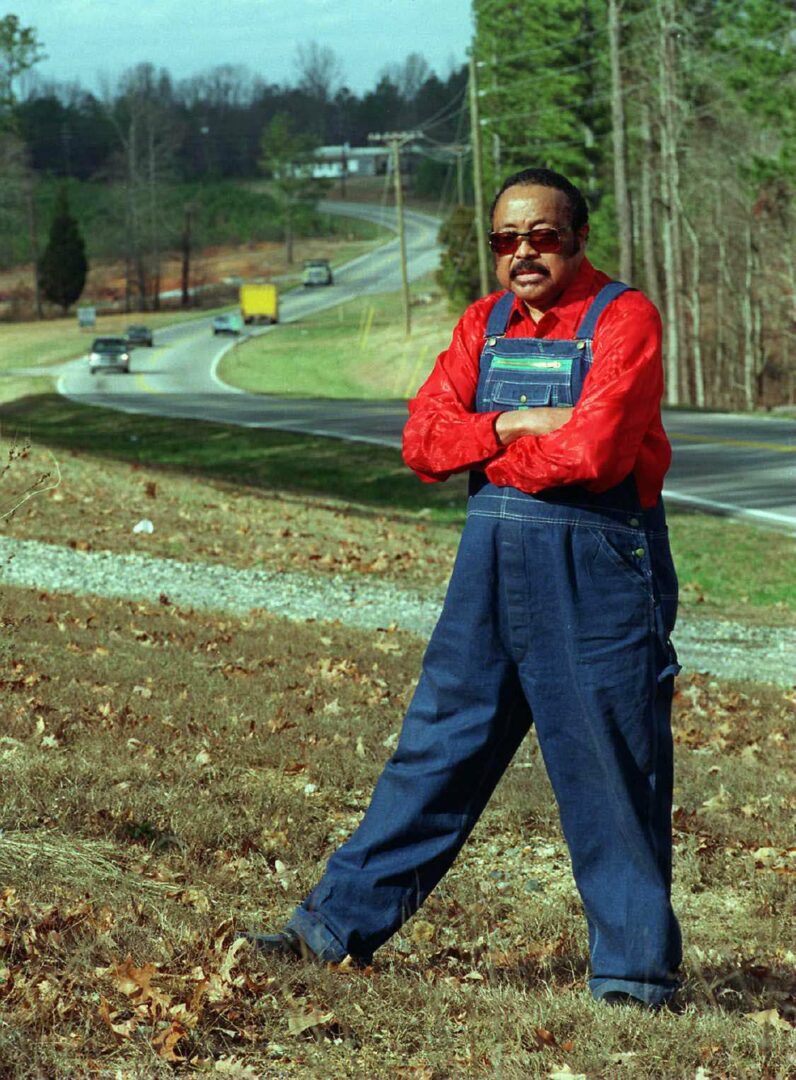

Williams died on November 16, 2000, after a three-year battle with cancer. Thousands of mourners filed past his body, dressed in his trademark denim overalls, red shirt, and red sneakers, as it lay in the International Chapel at Morehouse College. Williams is buried in Atlanta’s Lincoln Cemetery.

In 2001 the Georgia General Assembly passed House Resolution 409 honoring Hosea and Juanita Williams and directing that a portrait of them be placed in the state capitol. Williams’s papers are housed at the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, which hosted an exhibition of materials from the collection in 2008.