The Progressive Era refers to a period of varied reforms that took place throughout the United States over the first two decades of the twentieth century. While much of that change was enacted by the U.S. Congress under the leadership of three consecutive presidents—Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson—it was also a movement that generated a variety of changes at the state and local levels as well.

Most state governments, including Georgia’s, generated Progressive reforms that sometimes coincided with, but sometimes differed from, those enacted at the federal level.

Major areas of economic, social, and moral reform among southern states included prohibition, woman suffrage, the regulation of child labor, campaigns to abolish the convict lease system and reform the penal system, and expansion of educational opportunities and social services for marginalized groups. Paradoxically, the disfranchisement of Black voters was considered a reform by white Progressives in southern states who felt that it eliminated a major source of electoral corruption; segregation (or Jim Crow) laws imposed at the same time were also viewed as progressive by those who saw them as the only means by which racial peace could be achieved.

Progressives included not only political leaders—governors, legislators, and mayors—but also academics, educators, businessmen, large farmers, and both women and Black activists. All of these groups shared a basic belief in “energetic government”; they recognized both the responsibility and the ability of government, at federal, state, and local levels, to solve the many social, economic, and political problems that faced the rapidly modernizing nation at the turn of the century.

Progressivism’s Beginnings

In Georgia, as elsewhere, Progressivism was a far more urban-based and middle-class movement than was the Farmers’ Alliance of the 1880s or the Populist Party in the 1890s, yet it drew heavily on those agrarian reform movements in its emphasis on regulating railroads, banks, and corporations; on battling government corruption; and on holding government accountable for answering to the needs of special-interest groups in need of regulatory protection. With the collapse of the Populist Party by the end of the 1890s, power returned to the Democratic Party in what would be a one-party system for more than half a century.

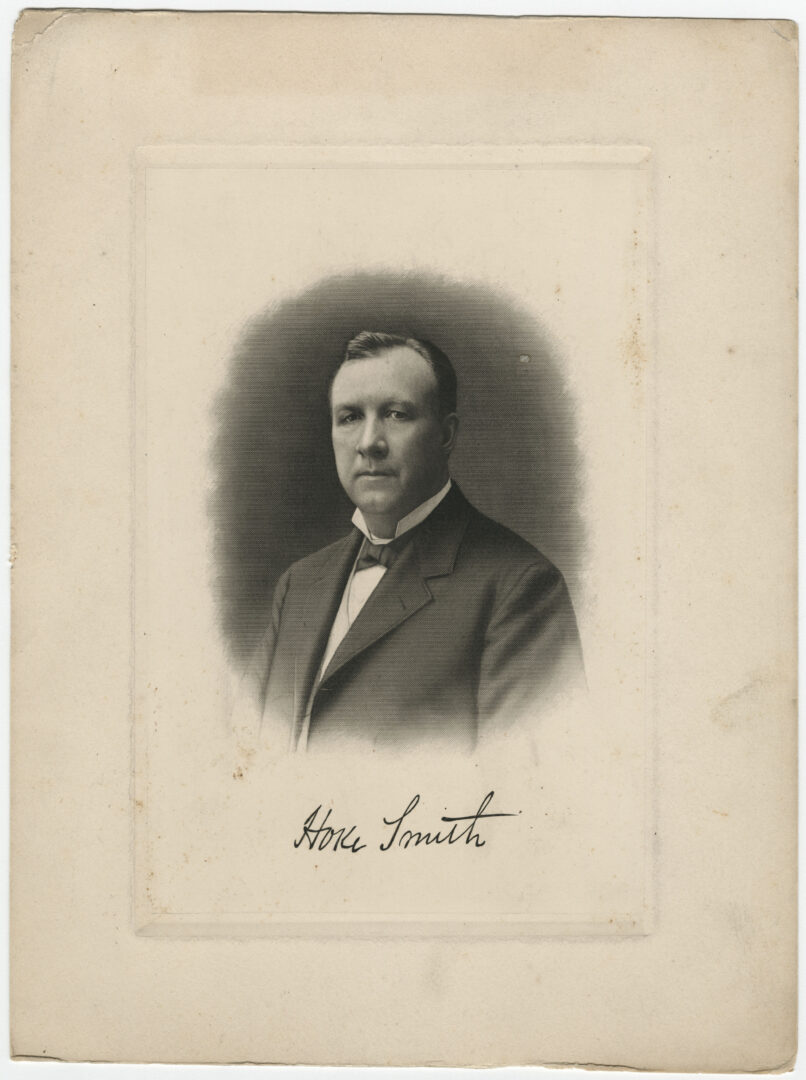

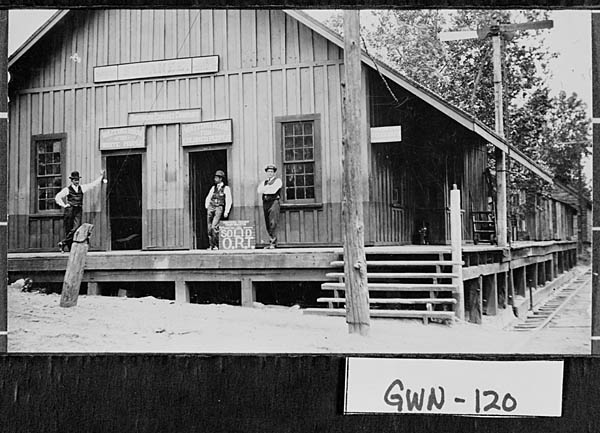

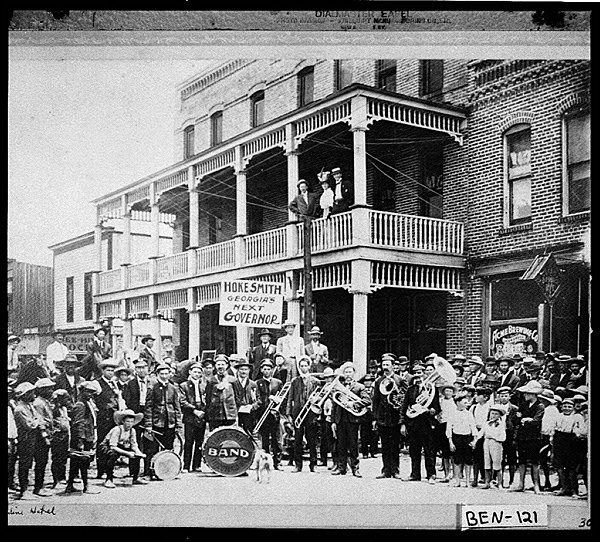

While Progressives could be either Republicans or Democrats in other parts of the country, it was the Progressive branch of the Democratic Party that imposed reform through new legislation in Georgia. While several governors during that era, from William J. Northen (1890-94) through Joseph M. Terrell (1902-7), advocated reforms of certain types, the movement remained a rather disparate effort until the governorship of Hoke Smith (1907-9, 1911), who offered the strong leadership to implement a full-fledged Progressive agenda and who did so with the endorsement of Thomas E. Watson, the former Populist leader and one of the strongest forces for reform in the state.

Much of the impetus for change in Georgia and the South came from journalists and academics—particularly social scientists—who discovered and exposed the social problems that cried out for correction. Labeled “muckrakers” by U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt, those who focused specifically on southern issues included the newspaper publisher Walter Hines Page, the pioneering sociological photographer Lewis Hine, and the journalist Ray Stannard Baker. W. E. B. Du Bois is Georgia’s most distinguished example of a progressive intellectual who wed social science to the analysis of public issues. While at Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), from 1897 to 1910, he carried out a series of nationally significant conferences and studies on the conditions of Blacks since Reconstruction. He also investigated Black landholders in Georgia, patterns of crime and incarceration, and the convict lease system. While in Georgia Du Bois founded the Niagara Movement, an association of Black intellectual activists, and in 1910 founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, in itself one of the most significant products of the Progressive Era.

Progressivism Implemented

After 1900 the Democratic Party of Georgia turned away from the radicalism of the Populist Party. As the now-dominant political organization in the state, the Democratic Party reflected the interests of an expanding urban middle class, a growing number of professionals in the state’s cities, wealthy farmers, and banking, commercial, and industrial interests.

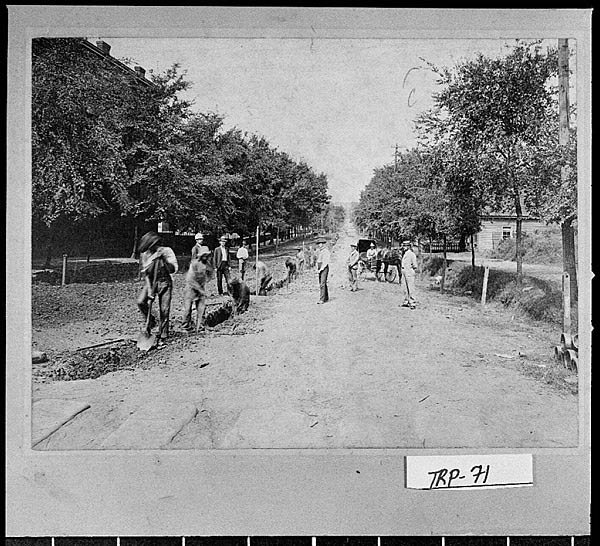

Progressive urban reformers in cities like Atlanta and Augusta turned to the principles of business efficiency as a good guide for government. They improved sewer lines and streets, added parks, and undertook city beautification projects. The goal was to create more livable cities, though not for all. There was little discussion, at first, of working conditions, hours, or wages for mill, factory, and lumber workers or for domestic servants and the poor.

The most important influence on the course of Progressivism was the decision by former Populist leader Tom Watson to endorse the candidacy of Hoke Smith for governor in 1906. The political collaboration of the “agrarian rebel” and a wealthy Democratic lawyer from the state’s largest city was not an obvious one. It was popular, however, as Watson’s endorsement still carried much weight with the state’s farmers, while Smith had come out strongly in favor of railroad regulation and improved public schools. Most telling was the fact that both Watson and Smith shared the goal of pushing Blacks entirely out of the state’s political system. They saw this step as necessary to promoting public peace and security, eliminating electoral corruption, and allowing the state to move forward in addressing its “real problems.”

Smith defeated Clark Howell, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, in a contentious primary, in which racially heated rhetoric contributed in part to the Atlanta race massacre that took place in September 1906. Smith coasted to victory in the general election, and once in office in early 1907, moved quickly on his campaign promises. The Georgia General Assembly allocated more education funds and gave the railroad commission broader regulatory powers over railroads to also include electric power companies, street railways, and gas lines. (Freight rates were not lowered.) The disfranchisement of Blacks was accomplished with the 1908 amendment of the Georgia constitution that required citizens to pass a literacy test before voting. The law’s inclusion of a “grandfather clause” as well as a property requirement guaranteed that most whites but few Blacks would qualify for the vote.

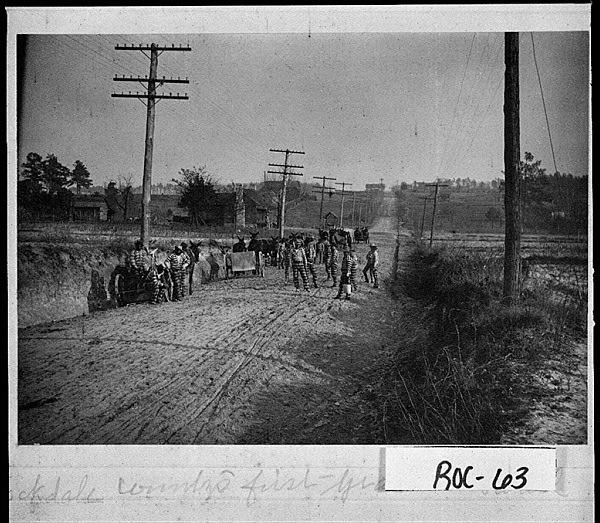

Farm and labor interests continued to call for penal reform, and in 1908 the General Assembly, with Smith’s strong backing, finally enacted a law prohibiting the convict lease system. A state farm was established and county detention camps provided for felons (about 90 percent of whom were Black), but otherwise not much else changed. In the absence of prison facilities, shackles, chains, abusive treatment (of men, women, and children), and labor on roads and highways were the prisoner’s lot.

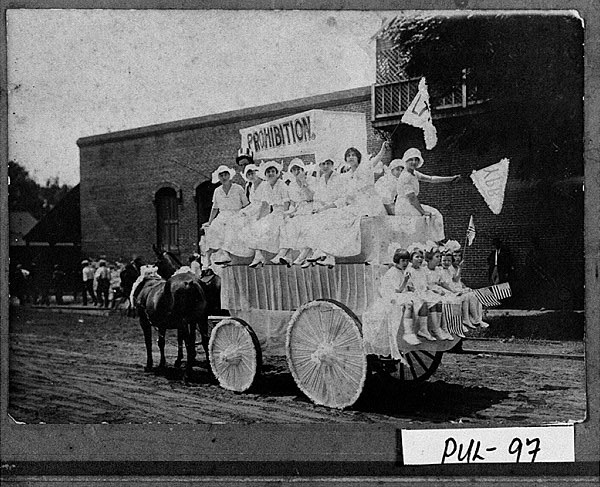

Prohibition

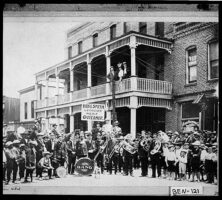

One issue that was not part of Smith’s formal campaign but that he fully supported was prohibition. The temperance movement in the state actually began much earlier, when the Georgia State Temperance Society formed in 1828, and was launched anew with the establishment of a state chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in 1880. Prohibition forces enjoyed the support of the Farmers’ Alliance and the Populist Party in the 1890s, and the issue quickly emerged as a major component of the Progressive agenda after the turn of the century. In 1905 the Anti-Saloon League (formed by evangelical Protestant men) organized in Georgia and helped broaden and unify support across the state. In Atlanta concern over saloons that catered to working-class African American men fueled prohibition advocates, who blamed Black saloongoers for rising crime rates in the city. Rumors of intoxicated Black men threatening sexual violence to white women inflamed whites, leading a mob to descend upon the Black community, in what became known as the 1906 Atlanta race massacre.

By 1907, 125 of the state’s 146 counties had voted to become dry. That same year the General Assembly passed a statewide prohibition law, the first in the South, that made the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages a crime. Over the next several years prohibition forces wrangled over the exceptions in the legislation, which permitted “near beer,” the storage of alcohol in lockers in private clubs, and the importation of alcohol from outside the state. In 1916 the legislature made possession of alcohol a crime. Amended many times, Georgia’s law became the strictest in the nation. Prohibition became national law when the states ratified the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. The law took effect the following year.

Education Reform

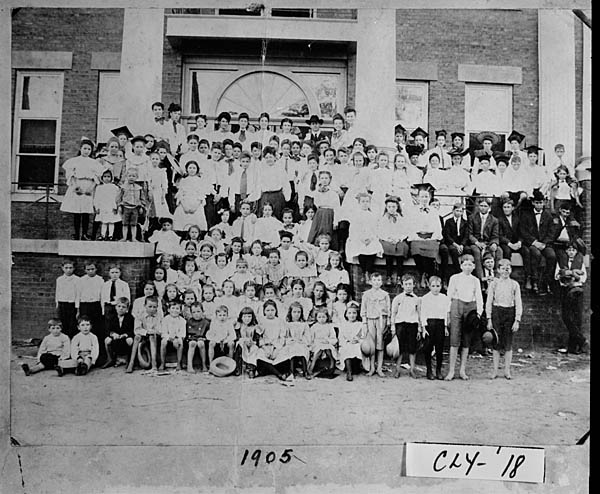

In the late nineteenth century most southern children, particularly in rural areas, received little more than an elementary education, which often meant no more than five or six years of schooling, during only three or four months per year, as dictated by the seasonal demands of agricultural work. Only about half of Georgia’s children attended school at all. Progressive reformers made the standardization of school attendance a priority, including compulsory attendance laws. Under Hoke Smith’s leadership, Georgia’s legislature, like those of other southern states, committed funds to the expansion of school facilities and the replacement of one-room schools with consolidated schools, more teachers, and higher grade levels. In 1916 a new Georgia law required school attendance for children between ages eight and fourteen for at least four continuous months a year.

In addition to state support, many of these education reforms were funded by northern philanthropic efforts, such as the Southern Education Board, established in 1901, and the General Education Board, a foundation sponsored by philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, who gave more than $53 million from 1902 to 1909 to study, publicize, and campaign for improved conditions in public education throughout the South. While Georgia still lagged far behind the rest of the nation, and even much of the South at the end of the Progressive Era, statistics from the early twentieth century indicate substantial improvement. In 1900 the average length of the school term was 112 days; in 1920, it had expanded to 145 days. Over the same period, per pupil expenditures in Georgia rose from 89 cents in 1900 to $3.13 in 1920; white teachers’ salaries also increased substantially. Between 1912 and 1919 new legislation and amendments to the state constitution incorporated high schools into the public educational system and required that state and local funding go toward their support as well as that of elementary schools.

Few in-state efforts incorporated Black schools into their reforms, though the northern philanthropic movements often made industrial education for African Americans a priority. Rockefeller’s General Education Board and the John F. Slater Fund provided considerable funding of county training programs for Black teachers of industrial arts. Anna T. Jeanes, a Quaker from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, gave more than $1 million to provide “rudimentary” education for rural southern Blacks in 1907, and a year later she established the Jeanes Fund to train Black teachers, again with industrial education as the primary focus. The program in Georgia began with six Jeanes teachers and eventually grew to fifty-three by 1939. Beginning in 1912, Julius Rosenwald gave money for the construction of more than 5,300 school buildings for Black children in the rural areas throughout the South, of which 242 were located in Georgia.

Public Health

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing Georgia during the Progressive Era was the health of its people. Some of the most serious problems were caused by living conditions. Almost all of the state’s rural homes, and many of those in its cities, lacked any means of sanitary sewage. Impure food, ignorance of the contagious and infectious nature of illnesses, and inadequate medical assistance added to public health risks. Pellagra was a particularly devastating disease caused by poor diet with little protein. Especially common in rural areas was hookworm, an intestinal disease contracted through bare feet that left its victims in a state of chronic fatigue and debility. (One estimate suggests that as many as 53 percent of all rural Georgians carried the disease in the early 1900s.)

An equally alarming problem, and one common to the state since its founding, was malaria, a mosquito-born disease that can cause fever, chills, exhaustion, and sometimes death. In 1900 Georgia ranked fourth nationally in the number of malaria deaths. Georgians were also plagued by smallpox, typhoid fever, venereal disease, and tuberculosis.

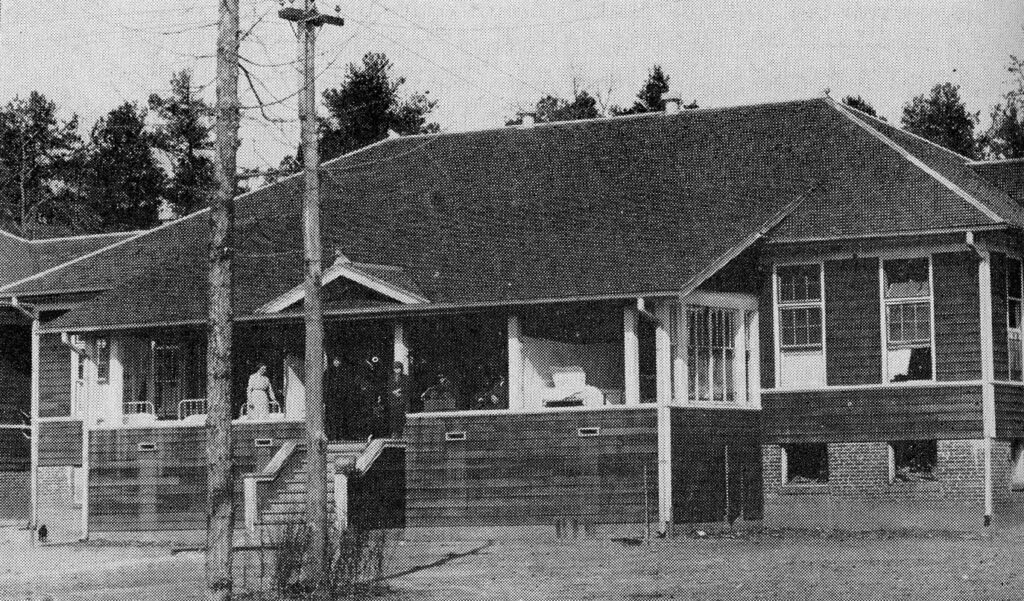

Solving these problems in the long term would involve a combination of education, medical science, government support, and access to health care. Georgia’s first serious step was taken in 1903 when the General Assembly created a new state Board of Health. (The first board of health existed from 1875 to 1900.) Located in the basement of the state capitol building, and with a meager annual budget of $3,000, of which $2,000 was marked for the secretary’s (a qualified physician) salary, the health board soon began an anti-rabies project and embarked on a program of publicizing information about infectious and contagious diseases. In 1905 it developed a bacteriological lab in the basement of the capitol, where it manufactured and distributed typhoid vaccines and diphtheria antitoxins. The health board also joined forces with other southern states and, later, with the 1909 Rockefeller Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease in the successful effort to eradicate hookworm.

At first, many doctors and public officials were suspicious of the new field of “public health,” while the legislature scrimped in allocating funding. Progress was by steps, however, and usually on the heels of an epidemic that underlined the importance of environment and hygiene. In 1908 the General Assembly authorized $25,000 for the state’s most ambitious health project yet, a public sanitarium for the treatment of tuberculosis in Banks County. In 1914 the General Assembly provided for a board of health in every Georgia county. Though at first few counties bothered to participate, by 1922 most counties had organized into a statewide public health network. The 1914 law also required the state to maintain vital records on the incidence of diseases and deaths—a critical step in identifying public health threats.

As important as these first steps were, the public’s needs vastly overshadowed the state’s capacities. Not until the 1930s and after, when federal programs allocated funds and program expertise to the state, did Georgia engage, and finally begin to solve, its most serious health problems.

Women’s Activism and Suffrage Campaign

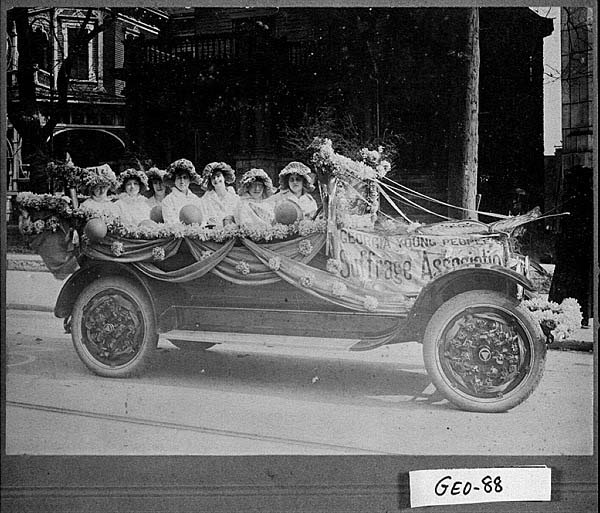

One of the more distinguishing features of the Progressive movement in Georgia, as nationwide, was the initiative and increasing leadership taken by women, Black and white, on a variety of fronts. Most of these were urban-based and middle-class women, eager to move beyond the domestic sphere dictated by Victorian America, who organized and became politically active. White Georgians, such as Helen Dortch Longstreet, Nellie Peters Black, and Julia Flisch, and African Americans, such as Lugenia Burns Hope and Selena Sloan Butler, worked through women’s clubs, neighborhood associations (primarily Black), and other charitable and civic organizations to raise consciousness and lobby legislators for the reforms they most ardently supported.

A number of women were active on several fronts, even when those causes may have seemed contradictory in ideological terms. Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas of Augusta, for example, held leadership positions in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in Augusta, and was president of the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association. She crusaded for a state industrial school for girls and for more humane treatment of female prisoners in the state’s jails. Yet she was also a leading proponent of more conservative “Lost Cause” efforts to commemorate the Confederacy and Confederate soldiers. Rebecca Latimer Felton championed prohibition and woman suffrage and attacked the convict lease system, yet she defended cotton mill owners against charges of child labor abuses and defended not only Black disfranchisement but lynching as well.

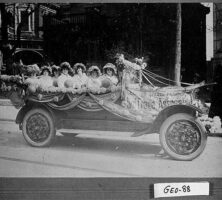

The culmination of women’s efforts was their campaign to win the right to vote. Georgia’s woman suffrage advocates began organizing as early as 1890. National leaders and prominent Progressive reformers like Susan B. Anthony and Jane Addams made supportive appearances in the state, while Rebecca Latimer Felton, Mary Latimer McLendon, Frances Smith Whiteside (Hoke Smith’s sister), and many of the women mentioned above worked to build support among Georgia’s women and the public. Yet they faced formidable opposition from other women, such as Mildred Lewis Rutherford and Dolly Blount Lamar, who headed the Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Pro-suffrage advocates faced a losing battle in a conservative state that was the first in the nation, in 1919, to reject the Nineteenth Amendment. Yet Georgia women finally gained the right to vote with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

Twilight of Reform

After being defeated by Joseph M. Brown in the 1908 governor’s race (Tom Watson had switched his allegiance to Brown), Hoke Smith regained office in the 1910 election. In his second term Governor Smith joined forces with Progressive interest groups to create a state Board of Education. High schools were created, teacher certification improved, and more funds appropriated for education. Smith also successfully pressed for legislation that set a sixty-hour work week for mill workers and made provision for a new Department of Commerce and Labor to enforce the law.

Smith’s second term lasted only a year (he moved to the U.S. Senate in 1911), and his departure from the governor’s office signaled a dampening in sentiment for reform, as no other governor exhibited the same Progressive spirit. Nevertheless, other reforms were generated by the state legislature. In 1914 the General Assembly, repealing a weak 1906 child labor law, enacted new provisions that set fourteen as the minimum age of employment (although there were exceptions). Lacking any provision for inspection or enforcement, however, the law languished on the books. By 1920 Georgia led the nation in the number of employed children aged ten to fifteen. In 1916 the legislature passed a compulsory school attendance law, but enforcement was almost impossible because of the number of exceptions granted. A more effective and enforceable child-welfare provision was a state law passed in 1915 that created a juvenile court system.

In 1916 the federal government provided a matching grants program for highway construction. This was a popular program in Georgia that appealed to business owners, farmers, railroad companies, and shippers. The General Assembly provided for a highway commission to coordinate state efforts. The availability of state prisoners offered a cheap and ready source of labor.

The U.S. entry in World War I (1917-18) diverted attention and legislative energies from the Progressive agenda. Woman suffrage—spurred in part by women’s leadership efforts in the peace movement to keep the United States out of the war prior to 1917, and their home front mobilization efforts during the war—is the only major reform achieved after the war’s end.

The Legacy of Reform

Because it facilitated economic growth, Georgia’s Progressive movement enjoyed the support of businesses, large land owners, and urban interests. When reform served a broad public (railroad regulation, highway construction, maximum hours for mill workers, and education) or accomplished moral and civic goals (juvenile justice, prohibition, and abolition of convict leasing), the state was in step with national trends.

It was out of step with the nation (though not the South) in its neglect of some of the poorest segments of society and its rejection of woman suffrage. Sharecroppers lost ground during the Progressive Era despite the fact that farmers’ initiatives before 1900 had set the stage for what came later. The disfranchisement of Blacks not only excluded 46 percent of the state’s population from the political system but also condemned many to a segregated underclass. The absence of a two-party system (distinctive to the South) probably diminished the depth and longevity of reform in the state.

Reforms were expensive and depended for their success upon the capacities of government. When Progressivism arrived in Georgia, the state was still in recovery from the human and economic disaster of the Civil War (1861-65). Further, the broadly supported priority of maximizing the power of county units while minimizing government expenses meant that the ad valorem or general property assessment tax (established in the Constitution of 1877), which kept taxes low, was the state’s main generator of revenue. Not until the existence of a program of general taxation (income, gasoline, automobile registration, and the salestax that began in 1951), and an economy and population to support it could morebe done. Progressive-era reform in Georgia was a modest but important first step in that direction.

Progressivism was the first of several major reform movements, and it shared with those later efforts an agenda of social justice, expanded economic opportunity, efficiency in government, and moral reform. Unlike the New Deal of the 1930s and the “Great Society” of the mid-1960s, which were nationwide programs instituted by single presidential administrations (Franklin D. Roosevelt’s and Lyndon B. Johnson’s respectively), and enacted solely by federal legislation, Progressivism was far more broad-based and less centralized or limited to governmental initiative. The civil rights movement was equally broad-based in the grassroots makeup of its proponents but was more of a single-issue, regionally based movement and was characterized far more by protest and by massive resistance and violent response to that protest. The goals of the civil rights movement were ultimately implemented by congressional legislation but carried out by the initiatives of the federal court judicial system. Much of the movement’s purpose was to undo the restrictions of segregation and disfranchisement that had been imposed on southern African Americans that had once been considered Progressive reforms.

Ultimately, Progressivism’s greatest legacy for Georgians and all Americans—and a central facet of all subsequent reform movements—lay in its underlying assumption that government at all levels could and should take responsibility for guarding the interests and the welfare of certain elements of society and should utilize the powers of legislation and regulation in so doing.