Georgia citizens in the nineteenth century relied on newspapers to keep them informed about what was happening outside their own towns and counties. The state could boast a few literary, religious, and agricultural magazines, but newspapers were by far the more important news source.

In times of crisis—war, economic distress, or natural disaster, for example—Georgians picked up newspapers to read about what had happened. This made the state’s sometimes small and struggling newspaper industry an important tool for government, politics, and business alike.

Newspapers took on added significance during the Civil War (1861-65), providing to Georgians not only information about the breakdown of the Union and the four-year conflict that followed but also a venue through which vital issues were debated before a broad reading public.

State Expansion and the Growth of Newspapers

As the nineteenth century began, Georgia had only five newspapers—two in Savannah, two in Augusta, and one in the state capital of Louisville—but soon newspapers appeared in several other towns. One was edited by a woman, Sarah Hillhouse, who in 1803 took over the Washington Monitor, in Washington, when her husband, David, died. She was the first woman editor in the state.

Georgia’s newspaper industry did not stay small for long. In the early part of the century, the drive for progress and greater economic prosperity for white settlers led to expansion toward the west, where Georgia planters and farmers found new land for their cotton and tobacco plantations. The discovery of gold in the north Georgia mountains brought many new settlers to that area as well.

With the state’s expansion came a greater need for newspapers. Politicians needed to communicate with their constituents, who were moving farther and farther away from the state’s main cities, Savannah and Augusta. Businessmen needed more and better ways to reach potential consumers, and citizens needed a means of keeping up with state and national issues. Every town of any size generated a demand for information. By 1812, for example, Athens, which had sprung up beside the newly founded University of Georgia, was home to one of the state’s eighteen newest weekly newspapers. The weekly Macon Telegraph was founded in 1826. Newspaper growth was also stimulated to some degree by the War of 1812 (1812-15) and, around midcentury, by the Mexican War (1846-48). People wanted to know what was happening in the distant battlegrounds, and their only source, besides personal letters and travelers, was newspapers.

Georgia’s expanding economy was the most important stimulant for newspaper growth. The state’s first daily paper appeared in Savannah in 1817, when the Columbian Museum and the Savannah Gazette merged and began publishing six days a week. The Augusta Constitutionalist became a daily in 1834, followed in 1837 by the Augusta Chronicle. Newspapers did not appear in Atlanta until the 1840s. Cornelius R. Hanleiter put down the first permanent roots of Atlanta journalism when he moved his newspaper, the Southern Miscellany, there from Madison in 1847. Hanleiter moved because he believed the westward railroad expansion meant that big things were in store for the hamlet, then called Marthasville.

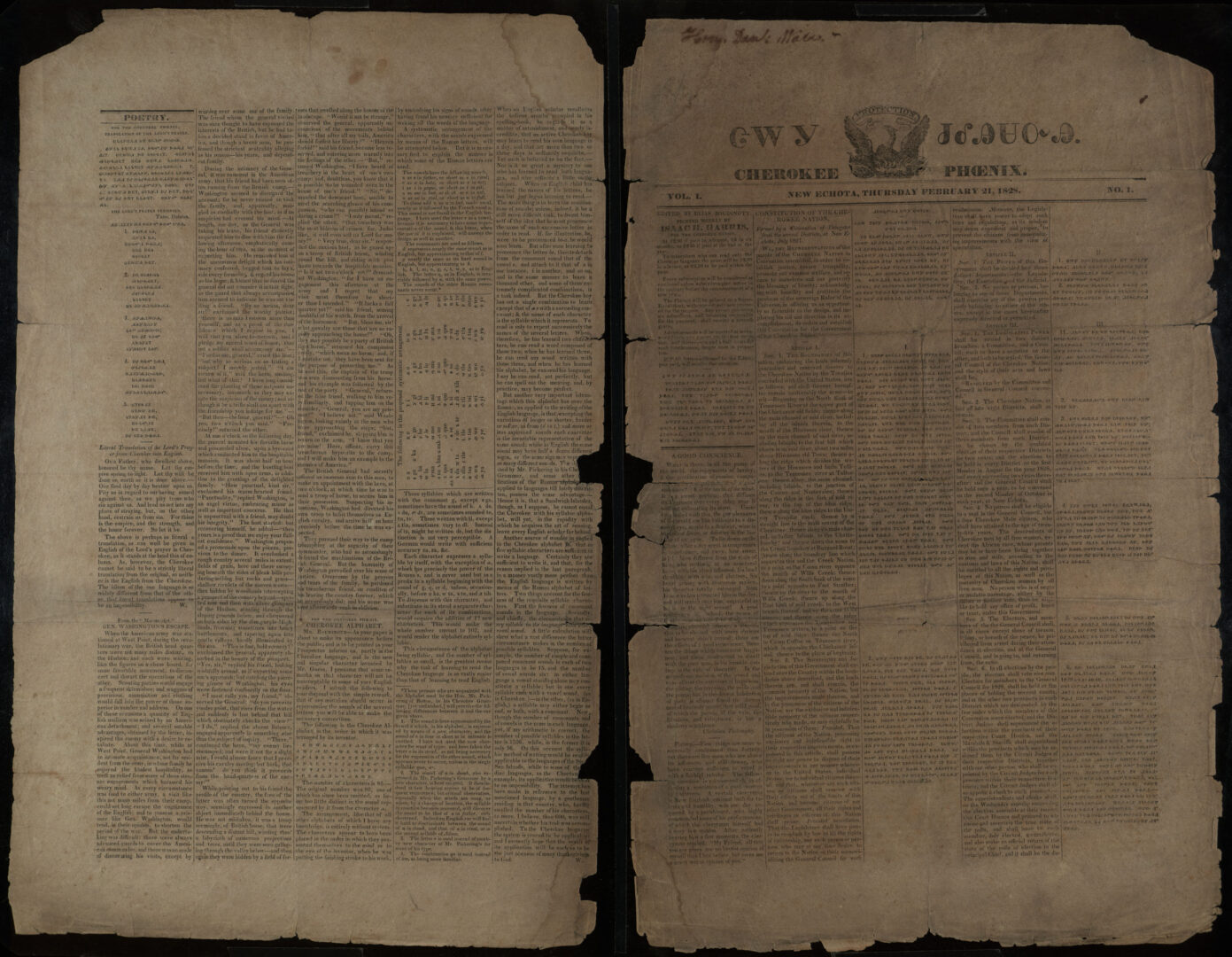

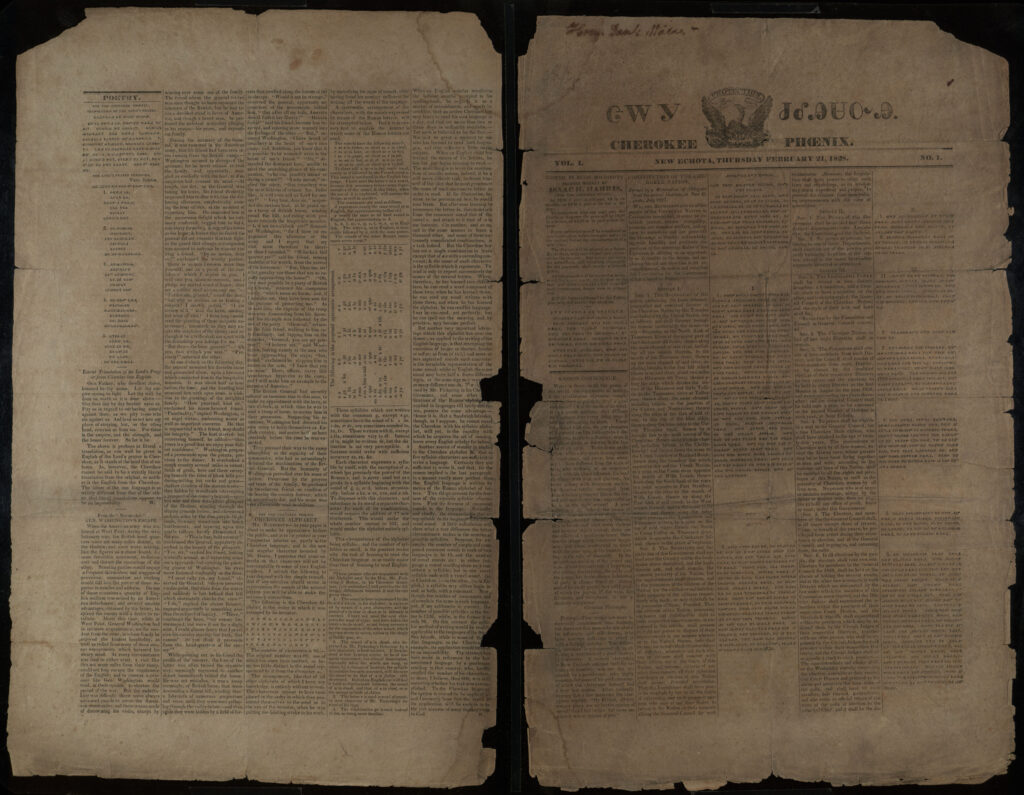

A Native American newspaper also arose in the early part of the century. The Cherokee Phoenix, edited by Elias Boudinot, appeared in 1828 to protest the removal of the tribe from land white settlers coveted. It attracted subscribers from as far away as Boston and New York, but few Georgians read the newspaper, which survived until it was suppressed in 1834.

By 1860 most of Georgia’s major cities had two or more newspapers, mostly weekly, but several daily. Atlantans had access to five locally published newspapers during the war years, two of which were daily. Most households did not subscribe to these papers; rather they were available to be read at various public venues, such as post offices, courthouses, and taverns, where men gathered and often discussed or debated what they read. As such, newspapers served not only as the major sources of information but also as the impetus for discussion and debate.

Partisan Journalism

Georgia’s antebellum newspaperswere mostly political in nature. Editors were bombastic political impresarios who touted party lines and perhaps even held political office. A large portion of their papers’ revenues came from political party patronage, even if the owners were not otherwise directly involved in the politics of the day. Politics was the basis for many newspaper rivalries and attacks in this period. Editors commonly harassed and abused other journalists, politicians, and even private citizens who were of a different political persuasion. These editorial attacks were almost always scathing. One particularly vile curse an editor might hurl at another was to call him an “apostate politician.” Editors also dug up dirt on their opponents. Given the southern value of honor and a good name, a number of editorial disputes resulted in duels. A few Georgia journalists carried weapons—generally pistols but sometimes knives—with them at all times.

Between 1820 and 1835 a number of political newspapers arose in Georgia to support the state’s two political parties, the Troup Party, which merged with the national Whig Party, and the Clark Party, which merged with the national Democratic Party. The change in 1824 to a popularly elected legislature increased the importance of the state’s political press, since politicians needed a mechanism by which to communicate with distant voters.

In the sectional conflicts of the late antebellum period, most Georgia newspapers leaned toward a Unionist position, though virtually all supported southern rights. The issue was whether the South’s rights could best be protected from inside or outside the Union.

The debates over nullification and secession were complicated by the issues of slavery and abolition. Most editors, themselves slave owners, opposed abolition and argued that vast social problems would arise should enslaved laborers be emancipated. Editors tried to downplay unrest. They said little in response to the Nat Turner revolt of August 1831, for example, though they increased the number of stern warnings they published about the possibility of further rebellion.

Secession and Civil War

By 1860 Georgia’s editors were deeply divided on the issue of secession. Even most of the Unionist editors did not rule out secession entirely, but neither were they convinced that the election of U.S. president Abraham Lincoln was grounds for immediate secession. They preferred to take a wait-and-see attitude. As secession became a reality, however, editors promised unity and grew quite expansive in their approval of the move to divide the Union. This unity, however, was short-lived.

Once it became apparent that the war was not going to be short and that certain civil liberties would have to be suspended to support the war effort, some newspapers again began to question the wisdom of the war. A fairly widespread peace movement arose in Georgia to foster opposition to the war and to the freedom-limiting measures Confederate president Jefferson Davis and the Confederate Congress had adopted, such as conscription, attempting to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and war taxes. One of the leading peace proponents was Alexander Stephens, the Confederate vice president and a Georgia native. Stephens, a master at managing relations with journalists, used his stable of press supporters, including the Augusta Chronicle and Sentinel and the Southern Confederacy of Atlanta, to spread his peace doctrine. By 1864, when the Georgia peace movement began to take hold, the state’s citizens were war-weary and receptive to the idea that it was time for the war to end. However, no opposition newspaper was ever officially suppressed or harassed by mobs.

Toward the end of the war, newspaper editors engaged in an intense debate over whether the Confederacy should arm enslaved persons as a means of coping with the military’s manpower shortage and whether those conscripted should be emancipated in return for their military service. The issue emerged in November 1864 when Davis proposed during his annual address to the Confederate Congress that enslaved men work in noncombatant jobs and eventually be granted emancipation. Soon thereafter, rival journalists at papers in Augusta, Macon, and other cities weighed in, as did readers whose letters to the editors were published. Both editors and readers were sharply divided, and both editorials and letters regarding this radical policy and its implications for the South’s future fueled an ongoing debate that lasted through March 1865, when the proposal was abandoned.

Difficulties in Publishing

Many obstacles existed to newspaper publishing in the nineteenth century. The difficulties were magnified by the Civil War and its attendant problems. Subscribers and advertisers were slow to pay their bills, and they were hard to find in adequate numbers in the small towns where most of Georgia’s newspapers were located.

Actually acquiring news was often a problem in the days before reporters became a fixture in Georgia newsrooms. Early in the antebellum period, the Savannah Georgian purchased a “news boat” so it could be the first to get news from incoming ships. In March 1863 several newspapers throughout the South organized the Press Association of the Confederate States of America, a private organization that telegraphed war news to papers in all parts of the Confederacy, at least to those areas where communication lines had not been destroyed. Georgia papers often reprinted much material that appeared in Richmond papers as well as those in New York, Washington, D.C., and other major Northern cities, as was common practice throughout the nineteenth century.

Getting presses, type, and printing materials was another challenge. The closest suppliers were in Philadelphia and New York. Paper came from Virginia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, though at least one paper mill, Greene County’s Scull Shoals Papermill, was operating in Georgia by 1808. Until it burned in 1862, a mill in Bath, South Carolina, just across the Savannah River from Augusta, supplied paper for many Georgia newspapers.

The Postwar Press

During Reconstruction the Georgia press slowly recovered from the destruction of the Civil War. Some of the financial support that might have gone to the native press was siphoned off by the Republican newspapers that began appearing in 1868. These newspapers were, for the most part, run on patronage from the state’s military governors. Several papers were involved in graft schemes. A common trick was to accept a legal advertising contract from the Republican government, run the ads, bill for them, and then bill again.

Reconstruction and the movement for economic development in the late nineteenth century unified the Georgia press as the Civil War had not. During Reconstruction editors exhorted Georgians to rebuild but to remain unbowed. Few of the state’s newspapermen worked to change the prevailing attitudes and laws designed to keep power out of the hands of Black Georgians. While newspapers may not have been entirely comfortable reporting on the activities of the Ku Klux Klan or other vigilante groups that appeared in the postwar period, neither were they quick to condemn lynchings of Black Georgians. More often, editors demonstrated their disapproval of mob justice and lynchings by limiting their coverage to a factual recounting of events without any of the usual commentary. The African American press had its beginnings in this period, but it remained very small until the twentieth century.

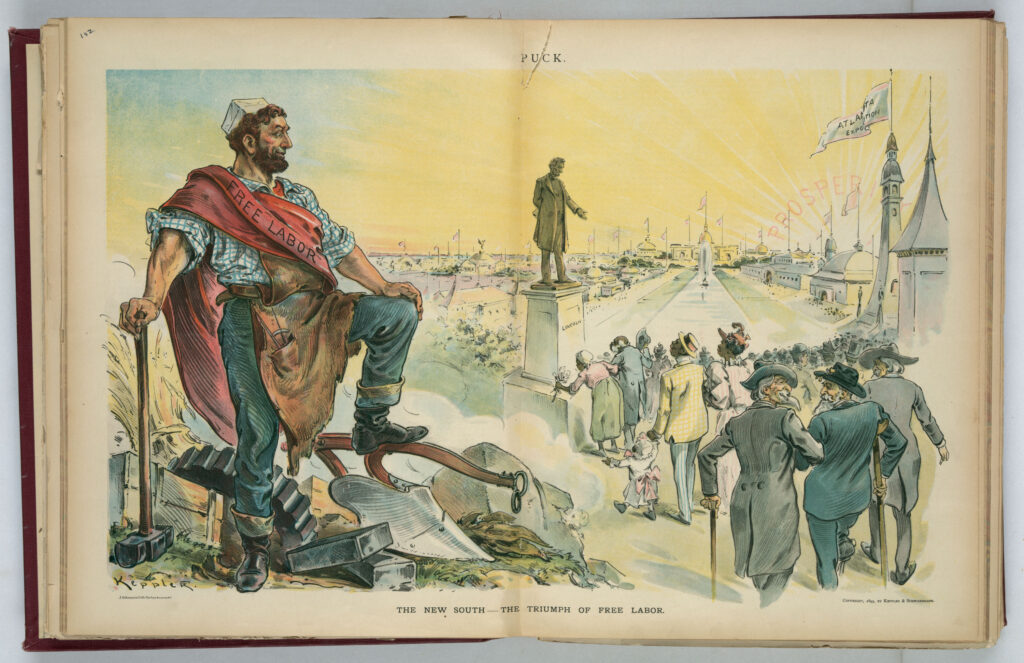

Economic development and the building of the New South, championed by Atlanta Constitution editor Henry W. Grady, was a dominant theme for journalists in the 1880s. Grady showed Georgia newspapermen how to use their voices to boost their communities, and as towns grew, so did newspapers. By 1890 the weekly edition of the Constitution had a circulation of 140,000. With growth, though, came greater expenses. Each year, the cost of producing a newspaper increased. Better machinery became necessary to keep up with readers’ demands for clearer text and pictures.

Journalism in Transition

As the twentieth century approached, new professional practices began to filter southward. Alexander St. Clair Abrams, a former employee of the New York Herald, brought the sensational techniques of yellow journalism to Atlanta in 1872, when he went to work for the Atlanta Herald. The Constitution, which would later adopt yellow journalism practices, severely chastised Abrams, but readers responded favorably to the format, and sensationalism found a safe haven in Atlanta.

By the turn of the century, Georgia’s newspapers had made several profound transitions. The state could boast nearly 300 newspapers, compared with five at the beginning of the century. Newspaper content was quite different from what it had been in the early part of the century. Rather than focusing on political commentary, Georgia’s journalists were providing their readers with news of the day. Even weeklies, which continued to practice partisan journalism much longer than most of the state’s dailies, had become community newspapers.

By the 1890s many newsrooms were lit by electricity, and presses ran on steam. News traveled not by horseback and mail but by telegraph and telephone. Georgia’s editors had repudiated violence and were becoming more concerned with ethics and professionalism. They had formed the state press association, and the state’s women journalists had their own professional organization. Georgia journalism had made the transition from the partisan press to a fully modern newspaper industry, despite the setbacks of the Civil War and Reconstruction.