The civil rights movement in the American South was one of the most significant and successful social movements in the modern world. Black Georgians formed part of this southern movement for full civil rights and the wider national struggle for racial equality. From Atlanta to the most rural counties in Georgia’s southwest Cotton Belt, Black activists protested white supremacy in myriad ways—from legal challenges and mass demonstrations to strikes and self-defense. In many ways, the results were remarkable. As late as World War II (1941-45) Black Georgians were effectively denied the vote, segregated in most areas of daily life, and subject to persistent discrimination and violence. But by 1965, sweeping federal civil rights legislation prohibited segregation and discrimination, and this new phase of race relations was first officially welcomed into Georgia by Governor Jimmy Carter in 1971.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Early Years of Protest

Although the southern civil rights movement first made national headlines in the 1950s and 1960s, the struggle for racial equality in America had begun long before. Indeed, resistance to institutionalized white supremacy dates back to the formal establishment of segregation in the late nineteenth century. Community leaders in Savannah and Atlanta protested the segregation of public transport at the turn of the century, and individual and community acts of resistance to white domination abounded across the state even during the height of lynching and repression. Atlanta washerwomen, for example, joined together to strike for better pay, and Black residents often kept guns to fight off the Ku Klux Klan.

Around the turn of the century political leader and African Methodist Episcopal bishop Henry McNeal Turner was an avid supporter of back-to-Africa programs. Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement in the 1920s gained support among Georgia African Americans, as did other national organizations later, such as the Communist Party and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Meanwhile, Black Georgians established schools, churches, and social institutions within their separate communities as bulwarks against everyday racism and discrimination.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

Protest during the World War II Era

The 1940s marked a major change in Georgia’s civil rights struggle. The New Deal and World War II precipitated major economic changes in the state, hastening urbanization, industrialization, and the decline of the power of the planter elite. Emboldened by their experience in the army, Black veterans confronted white supremacy, and riots were common on Georgia’s army bases. Furthermore, the political tumult of the World War II era, as the nation fought for democracy in Europe, presented an ideal opportunity for African American leaders to press for racial change in the South. As some Black leaders pointed out, the notorious German leader Adolf Hitler gave racism a bad name.

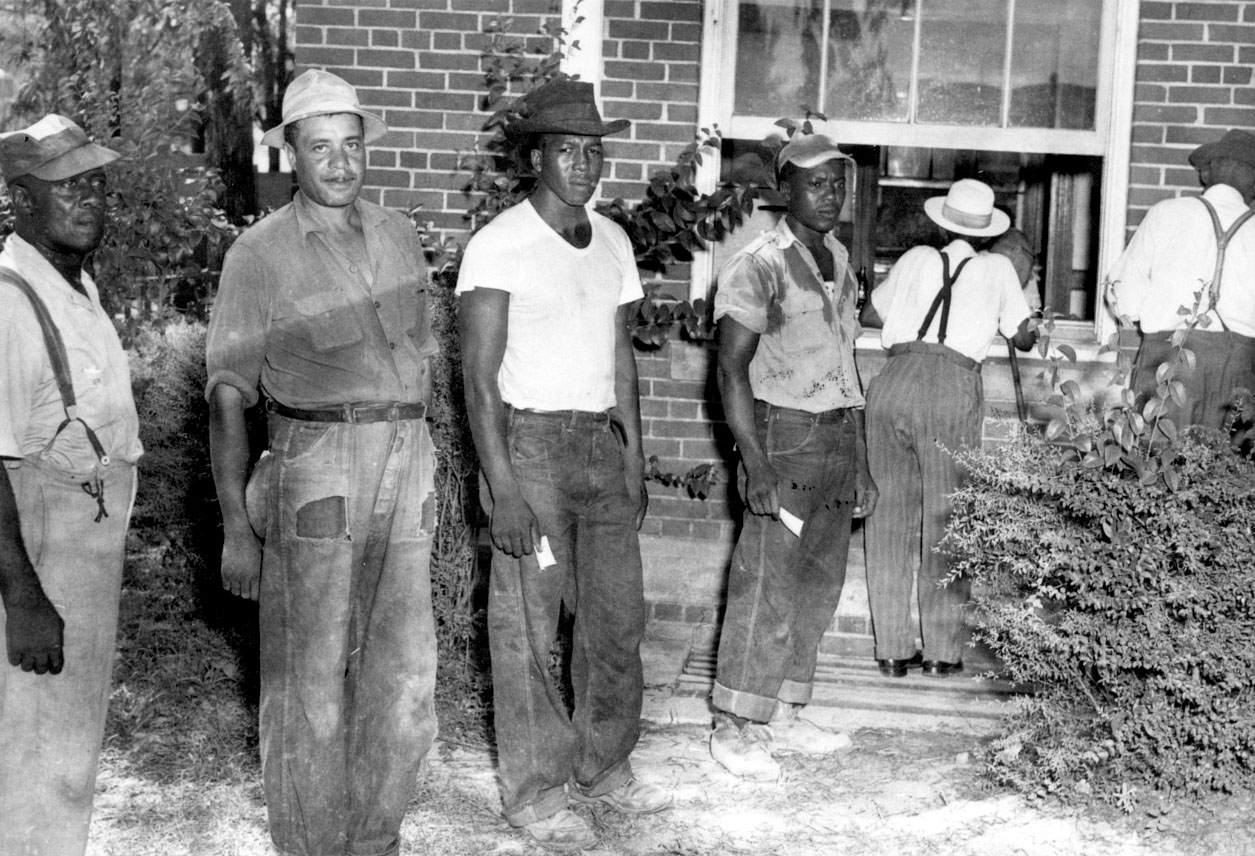

African Americans across Georgia seized the opportunity. In 1944 Thomas Brewer, a medical doctor in Columbus, planned an attempt to vote in the July 4, 1944, Democratic primary. Primus King, whom Brewer recruited to actually attempt the vote, was turned away from the ballot box. Several other African American men were turned away at the door. The following year a legal challenge (King v. Chapman et al.) to the Democratic Party’s ruling that only white men could vote in the Democratic primary was successful. The decision was upheld in 1946. In response, Black registration across the state rose from a negligible number to some 125,000 within a few months—by far the highest registration total in any southern state. In the larger cities, notably Atlanta, Macon, and Savannah, local Black leaders used their voting power to elect more moderate officials, forcing concessions such as the appointment of Black police and higher spending for Black schools. Under the charismatic leadership of the Reverend Ralph Mark Gilbert from Savannah, the NAACP grew to more than fifty branches by 1946.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

At a state level, Black leaders confidently sought to prevent the notorious white supremacist Eugene Talmadge from being elected governor for the fourth time. In his campaign speeches, Talmadge asserted that “the election tomorrow is a question of white supremacy.” Talmadge won the 1946 election through a combination of violence, fraud, and the vagaries of Georgia’s county unit election system. In the weeks leading up to the Democratic primary, his supporters had systematically challenged the qualifications of Black voters and purged them from electoral rolls.

In the primary, moderate Democrat James V. Carmichael, supported by Governor Ellis Arnall (who had previously defeated Talmadge and was prevented by the state constitution from a succeeding term), won the popular vote over Talmadge by 313,389 to 297,245 votes. Owing to the county unit system that gave disproportionate power to rural voters, and which would be abolished by the federal courts in 1963, however, Talmadge secured victory by winning the county unit vote 242 to 146. But Talmadge died before he could take office. The resulting “three governors controversy” led to his son, Herman Talmadge, who had not even run for the office, being selected governor by the state legislature.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Herman Talmadge’s victory ushered in a resurgence of white supremacy. Time magazine quoted a Georgia voter who said, “Pore ol’ Georgia—first Sherman, then Herman.” Segregation was tightened up in the statute book, state officials sought to outlaw the NAACP, and vigilantes targeted local Black leaders. Gilbert, despairing over the collapse of the state network of Black protesters, resigned from the leadership of the NAACP. Brewer, who had received death threats from a local Klan member, was assassinated on a Columbus street in 1956 by an unknown assailant, and the group he had founded to oppose white supremacy disbanded.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

During the ensuing decade, defenders of white supremacy powerfully interlinked their attack on Black insurgency with the more general fear of communism. Organized Black protest continued on a significant scale only in Atlanta, Macon, and Savannah, which became relative oases of moderate race relations in the state. Yet even there, strict segregation continued and violent assaults on Black residents were frequent.

The segregation of public schools in Georgia and other southern states was declared unconstitutional in 1954 with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Many white Georgians resisted integration and advocated closing schools rather than abiding by the court’s decision. In 1960 Georgia governor Ernest Vandiver Jr. formed a special committee chaired by Atlanta attorney John A. Sibley to conduct public hearings on the issue. The committee, known as the Sibley Commission, ultimately recommended local option on the matter.

Mass Protests during the 1960s

Copying the principles of nonviolent mass confrontation elsewhere in the South, Black Georgians in the major cities (and students in particular) resumed the assault on white supremacy and segregation during the early 1960s. If urban protest was a common phenomenon across the region, however, each community had its own distinctive story to tell.

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.

Of all Georgia’s cities, Albany garnered the most national headlines because of the involvement of Martin Luther King Jr. in a mass protest campaign during 1961-62, called the Albany Movement. King’s presence certainly bolstered the scale of the existing protests, with up to 1,200 Black residents spending time in jail (sources on the mass jailing numbers vary, from 750 to 1,200). However, divisions among protest leaders (King’s brief presence was resented by some student activists), tactical mistakes, the machinations of local police chief Laurie Pritchett, and the stubborn defense of white supremacy meant that the campaign was unable to force a citywide desegregation agreement in the short term. It was King’s worst setback in the South, although in Albany itself residents and student volunteers continued to press for racial equality, with some success, long after King had moved on.

Reprinted from Freedomways

In Savannah, a united, widespread, and unremitting campaign led by W. W. Law, head of the local NAACP, forced city leaders to agree to desegregate public and private facilities from October 1, 1963, some eight months ahead of federal civil rights legislation. In his 1964 New Year’s Day address, Martin Luther King Jr. described Savannah “as the most desegregated city south of the Mason-Dixon line.” Law himself was fired from his job as a postman during the height of the crisis but was reinstated when the trumped-up nature of his charges became a national scandal. Georgia’s other notably successful movements were in Brunswick, Macon, and Rome, where Black leaders often used the threat of heightened protest to force anxious city governments to take the lead in avoiding social unrest.

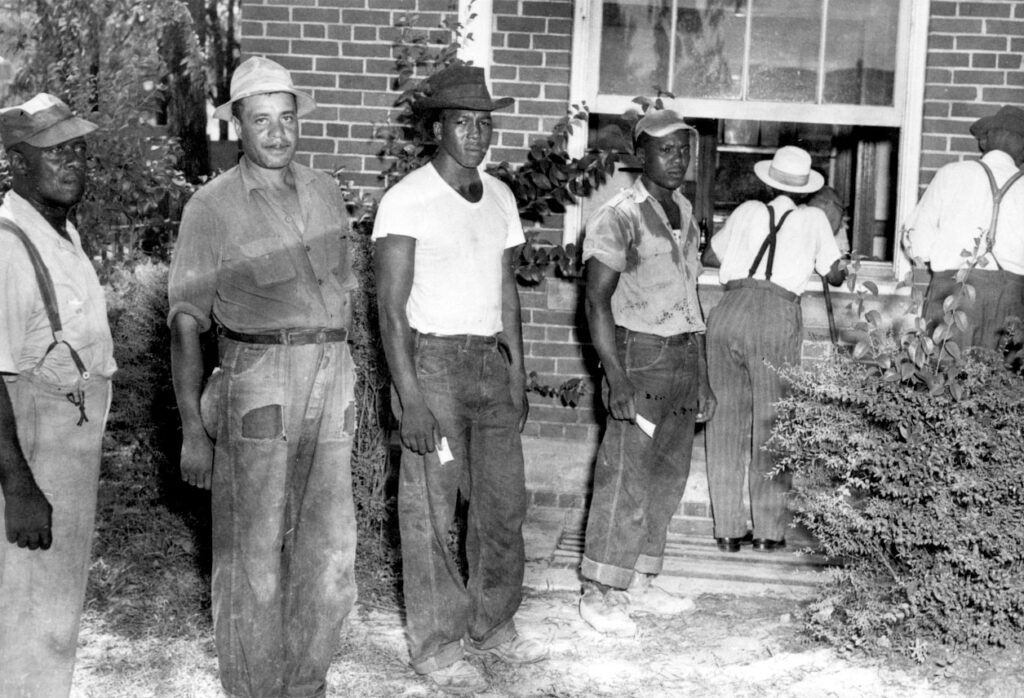

Students in Atlanta were the first to respond to protests elsewhere in the South, and under the leadership of students Lonnie King and Herschelle Sullivan, they organized a sophisticated and durable campaign. The manipulative behavior of the city government, hiding behind its slogan of “the City Too Busy to Hate,” coupled with the hesitant support of Atlanta’s traditional Black leadership, however, prevented the movement from securing a swift end to segregation. Indeed, at least 103 southern cities had desegregated their lunch counters before Atlanta, and student leaders themselves wrote to Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. in 1963, “Three years have passed without our having realized the goals which we set down.”

Photograph from Corbis

Protesters in Augusta also faced insurmountable and often violent opposition, and Black leaders in Columbus, still reeling from the murder of Thomas Brewer, were reluctant to launch a major campaign.

Protest in the Countryside

Protest away from the major cities, however, was comparatively faltering and sporadic. Some Black leaders commented ruefully that the civil rights movement stopped in Perry, a small town to the south of Atlanta. The tradition of white supremacy and violence coupled with Black poverty and economic dependence countered any prospect of widespread organized protest.

Counties like “Terrible” Terrell and “Bad” Baker in southwest Georgia were notorious for the violent antics of local police. Under the leadership of Charles Sherrod, a young Black preacher from Virginia, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) targeted Georgia’s notorious southwest Black Belt region in an attempt to overturn the worst vestiges of rural white supremacy. “Our criterion for success is not how many people we register” to vote, Sherrod explained. “We feel that we are in a psychological battle for the minds of the enslaved.”

Seeking to build up local leaders, SNCC volunteers lived in the Black Belt, far away from the attention of journalists covering the civil rights movement. Many were shot, and student leaders in Americus were charged with insurrection in 1963—a crime that carried the death penalty. Although they were ultimately released, the ferocity and economic strength of white supremacists meant that SNCC’s work was by necessity piecemeal and long term—indeed some of the volunteers, including Sherrod, made the region their permanent home.

The Continuing Struggle for Civil Rights

In many ways, the passing of federal civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965 did not mark the end of the civil rights struggle in Georgia. The legislation barely addressed problems faced in many of the poorer Black city precincts, where issues of squalid housing, unemployment, and police brutality dominated. During the summer of 1965, riots erupted across the state, particularly in Atlanta. Georgia’s largest riot occurred in Augusta in 1970, triggered by the torture and murder of a Black teenager in a city jail but reflecting many years of simmering tension. In some of the most impoverished areas around Vine City in Atlanta, a group of SNCC workers sympathetic to Black Power separatism sought briefly to organize a project, in 1965, to empower the poor. As late as 1987 civil rights leaders led a march in Forsyth County —a county that warned Black visitors not to “let the sun go down on your head.”

Photograph by Wikimedia

More generally, the federal civil rights legislation of 1964 and 1965 ushered in a new phase in Georgia’s struggle for racial equality. In many small towns, protests to force integration began only after 1965, and often many years later.

In her book Praying for Sheetrock Melissa Fay Greene describes how in McIntosh County in the early 1970s, “the epic of the civil rights movement was still a fabulous tale about distant places to the black people of McIntosh.” Sheriff Thomas Poppell controlled the county through a “system of favoritism, nepotism, and paternalism” and manipulated the Black vote to stay in office. It was not until one Friday afternoon in 1972, when Darien’s police chief shot and seriously wounded a Black garbage worker for disturbing the peace by drinking and arguing with his girlfriend, that the Black community in McIntosh County finally got involved in the fight for civil rights.

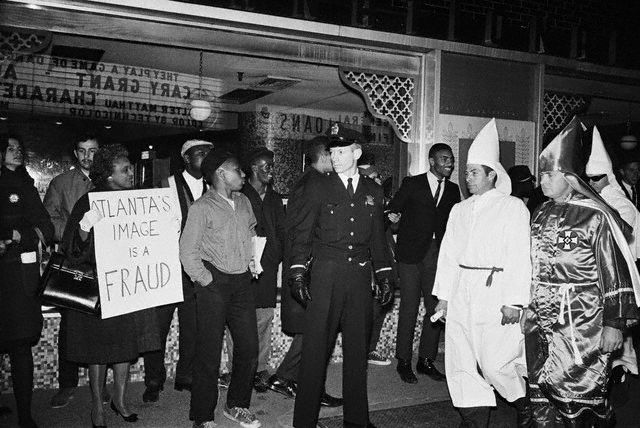

In politics, civil rights leaders sought to effectively mobilize Black voters and also oppose the gerrymandering of political districts that decreased the power of the Black vote. By 1980 Black Georgians still represented less than 10 percent of the total number of elected officials in the state, although notable successes included the elections of Andrew Young to the U.S. Congress in 1972 from a majority-white district, and Maynard Jackson as Atlanta’s first Black mayor in 1973. Young was the first Black congressman from Georgia since Reconstruction.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Herman Talmadge lost his campaign for reelection to the Senate in 1980—a result that Jackson claimed showed the importance of the Black electorate: “You cannot spit in our eye and tell us it’s raining.” Talmadge’s defeat, however, was probably due more to bad publicity generated by problems in his personal life.

In education, civil rights leaders sought to hasten the integration of schools and protect the jobs of senior Black teachers. By the 1980s, however, perhaps the greatest single issue was the continued economic hardship faced by the poorest Black (and white) Georgians. Such were the pernicious consequences of slavery and white supremacy that civil rights leaders still faced a struggle for racial equality into the twenty-first century.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.