The stock market crash in the waning days of October 1929 heralded the beginning of the worst economic depression in U.S. history.

The Great Depression hit the South, including Georgia, harder than some other regions of the country, and in fact only worsened an economic downturn that had begun in the state a decade earlier. U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s programs for economic relief and recovery, known collectively as the New Deal, arrived late in Georgia and were only sporadically effective, yet they did lay the foundation for far-reaching changes. Not until the United States’ entry into World War II (1941-45) did the depression in Georgia fully recede.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Georgia’s Economy in the 1920s

Much of the nation was enjoying a manufacturing and production boom in the 1920s, but a combination of overproduction, foreign competition, and new man-made fabrics, such as rayon, led to falling cotton prices in Georgia. By the mid-1920s, the effects of the boll weevil, which first arrived in 1915, had ravaged Georgia’s cotton fields and further decreased small farmers’ prospects for making a living. Between 1918 and 1928 the price of cotton decreased from 28.88 cents/pound to 17.98 cents/pound, and then bottomed out in 1931 at 5.66 cents/pound. To keep up with the lower prices being offered for their products, farmers needed to purchase expensive new farm machinery, but only a few rich landowners had the money to afford such investments.

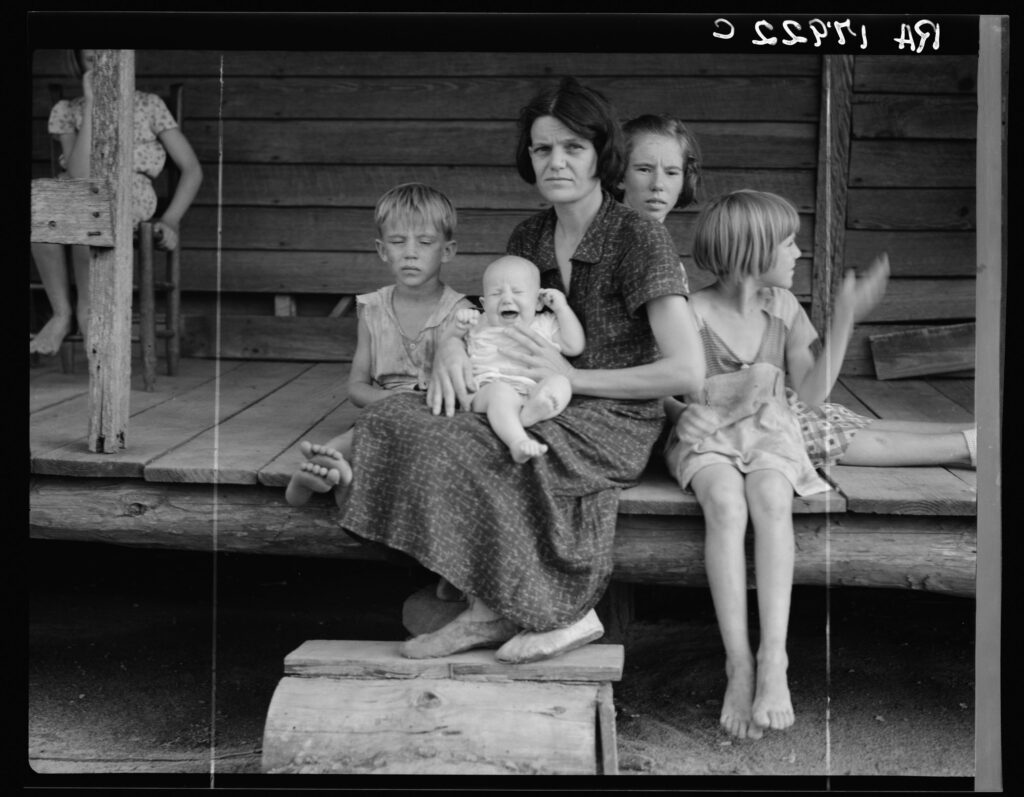

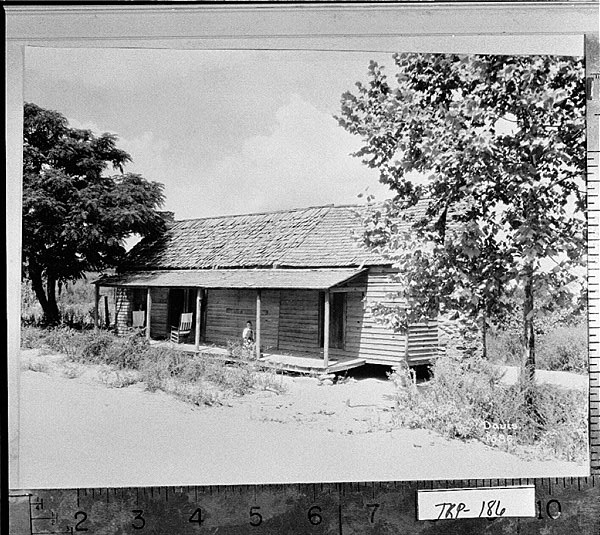

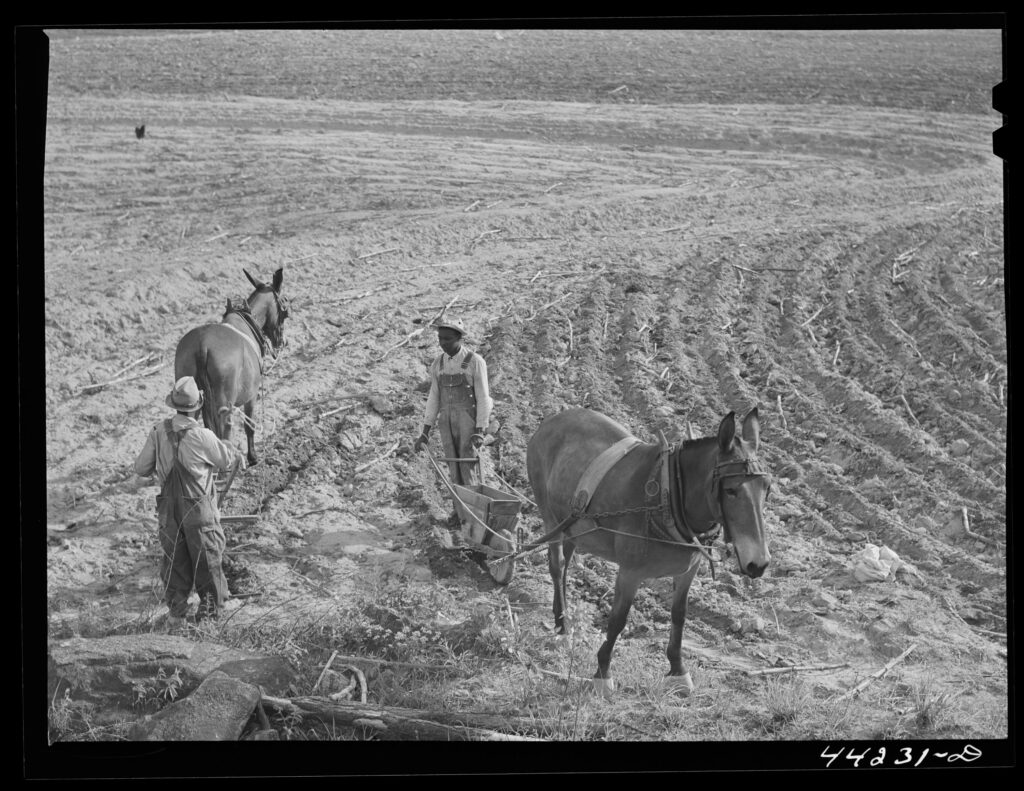

On top of the boll weevil’s effects and decreasing cotton prices, a three-year drought beginning in 1925 and an insufficient irrigation system further depressed Georgia’s agricultural economy. Some, especially Black southerns facing racial violence and low wages, abandoned their farms and moved to cities or out of the state, contributing to the ongoing Great Migration in northern states. Others were forced off their land by foreclosure and became sharecroppers on terms dictated by large landowners. On the eve of the Great Depression about two-thirds of farm land in the state was operated by sharecroppers. The majority were poor whites who lived on an annual per capita income of less than $200.

Conditions were harsher for Black Georgians, whose entanglement in the sharecropping system dated back to the end of the Reconstruction era. While some still owned their own farms in the 1920s, many were forced off their land entirely by declining prices and into menial jobs in towns and cities. Others took the now-familiar path of migrating to urban areas in the state or industrial centers in the North, often joining relatives who had migrated during the mid-1910s. By 1935 just 12 percent of Blacks owned the land they worked.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The root of Georgia’s rural depression in the 1920s was the decades-long dependence on cash-crop agriculture. (“Cash crops” are crops that are grown to sell, rather than crops that are grown for personal food or to feed livestock.) Cash-crop production placed enormous pressure on farmers to plant every available acre of land with cotton, which eventually depleted the soil. Outdated and careless practices, such as intertilling (planting short crops beneath tall crops, which increases productivity but depletes the soil) and the plowing of furrows without respect to the land’s contour, further drained topsoil, leaving the land gashed and gullied. Making matters worse, the removal of much of the state’s natural forestland eliminated one of nature’s most effective barriers to erosion. Georgia’s land, economy, and farmers were already wearing out when the Great Depression began.

Economic Crisis

The beginning of the Great Depression can be traced to the stock market crash of Tuesday, October 29, 1929 (also known as “Black Tuesday”). The 1920s were a time of increased stock market speculation. Many people, not just wealthy investors, invested in the stock market hoping for high returns. There was so much demand for stock (a share of ownership in a company) that stocks quadrupled in value between 1920 and 1929. Underlying problems in the economy, however, including an increasing number of poor sharecroppers, led to the sudden decrease in stock values on Black Tuesday. While this had the immediate effect of ruining many people’s investments, it also led to a banking crisis in which many banks failed, and the money in them was lost.

The depression’s immediate impact on Georgia was much like that throughout the nation as a whole. Bank failures were common, and in small towns and communities opportunities for loans dried up. Small business owners were especially vulnerable. Less money in local circulation meant fewer paying customers; with the absence of credit and financing, these business owners quickly went under.

Large landowners were usually able to ride out the depression; a small number of farmers who made the transition from cotton production to soybeans, peanuts, corn, livestock, and hogs had resources to fall back on. For the rest of Georgia’s farmers (69 percent of the population was rural in 1930), the depression was a catastrophe.

First, the state experienced its worst drought on record in 1930-31. As the depression wore on, the defects and negative trends of cash-crop agriculture became magnified. The typical Georgia farm family had no electricity, no running water, and no indoor privies. Diets were inadequate, consisting mainly of molasses, fatback, and cornbread. The poverty of the state’s most rural counties made the support of even minimal education standards impossible. There were few rural clinics, hospitals, or health care workers. Some counties had no health facilities at all. Naturally, sicknesses occurred, with pellagra, tuberculosis, and malaria being common. In Preface to Peasantry: A Tale of Two Black Belt Counties (1936) the sociologist Arthur F. Raper used these words to describe the conditions in the Black Belt of the South: “depleted soil, shoddy livestock, inadequate farm equipment, crude agricultural practices, crippled institutions, a defeated and impoverished people.”

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Urban residents tended to fare better than rural inhabitants. Savannah was protected by the city’s pivotal role as a seaport and exporter, while Savannah’s and Brunswick’s pulp industry expanded rather than declined in the 1930s. Textile and cottonseed-oil mills continued in cities where they were already established, such as Augusta, Dalton, Griffin, LaGrange, Macon, Rome, and West Point. Businessman Jesse Jewell of Gainesville was inspired by the harsh conditions of the depression to pioneer changes that would transform that city’s and north Georgia’s poultry industry. With its textile mills and iron foundries, Columbus managed to hold on to its position as an industrial leader in the state. Nevertheless, Georgia’s manufacturers were not exempt from national market trends and periodically resorted to reductions in hours and wages and even layoffs of workers.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

As the state’s largest city and one of the South’s most important financial, transportation, and industrial centers, Atlanta and its economy were more insulated than most. Professional workers in the health and legal fields kept their clients. Craft workers stayed busy. For most others, work was uncertain, and even those at the highest rungs worried about their jobs and income. Only 48 percent of the city’s workforce was gainfully employed, according to the 1930 U.S. census. The conditions in the slums of the city (appalling even before the depression) worsened as poor migrants from Georgia’s rural counties arrived penniless.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Even for those with jobs life was far from rosy. The Report to the President on the Economic Conditions of the South (1938) estimated that of the employed workers in the South’s largest cities, more than half could not afford “an adequate diet.” The report went on to note that among “white nonrelief families” with incomes less than $500, one-third did not have indoor running water, one-half did not have a kitchen sink or drain, and none had gas or electricity for cooking.

Despite hard times, Atlanta remained (as ever) optimistic about its future. Many of its businesses and larger retail establishments were able to survive, while some even experienced modest growth.

The Black Population

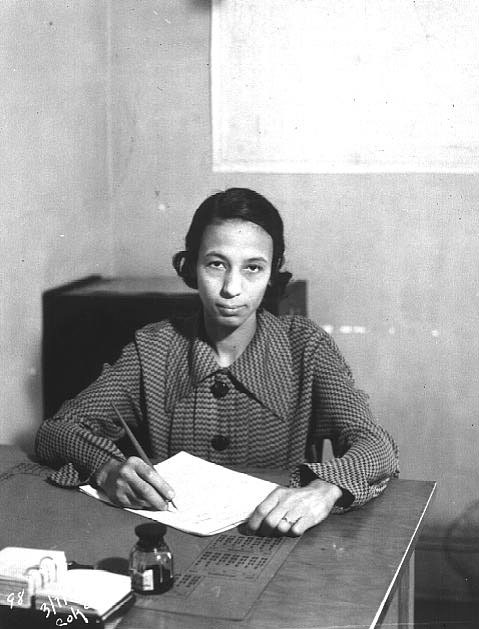

For the state’s African American population, as the blues singer Lonnie Johnson put it, “Hard times don’t worry me / I was broke when it first started out.” Blacks were already condemned by Jim Crow before the depression to inferior levels of education and the lowest-paying menial jobs. The income of rural Blacks was about half that of rural whites. In the entire state there were only four Black insurance companies, one bank (Citizens Trust Bank in Atlanta), and one wholly owned newspaper. According to the 1930 U.S. census, there were 10,110 Black professionals in Georgia (out of a population of 1,071,125), the majority being clergymen and teachers. Hospitals for Black patients existed only in the largest urban areas. The Great Depression slowed the Black migratory stream north but did not stop it entirely. In 1890 African Americans accounted for 47 percent of Georgia’s population and by 1930 just 37 percent. By 1940 that figure fell slightly, to 35 percent.

The New Deal and Recovery

President Roosevelt, who became a frequent visitor to Warm Springs for polio treatment beginning in the mid-1920s, understood the tangled web of Georgia’s deep-rooted racial, social, and economic problems from firsthand observation. With his inauguration in March 1933, his administration’s New Deal economic relief and recovery programs promised to bring positive change to the state.

The New Deal’s implementation in Georgia, however, was stalled by Governor Eugene Talmadge, who was elected in 1932 on a platform of cutting taxes and state services. He characterized Roosevelt and the New Deal as an outside intrusion into the state’s local affairs and a “communistic experiment.” He did everything he could (with some success) to slow the New Deal’s arrival in the state. However, Talmadge did little to address the state’s economic crisis, and in 1936, promising to bring the New Deal to Georgia, state House Speaker E. D. Rivers was elected governor by a wide margin. Rivers made significant strides in implementing much-needed reforms at the state level, but during his second term (1938-40) his administration faced problems of unpopular tax policies and charges of corruption. In 1940 Talmadge won reelection, but the changes begun by Rivers and Roosevelt had already laid the foundation for a new future.

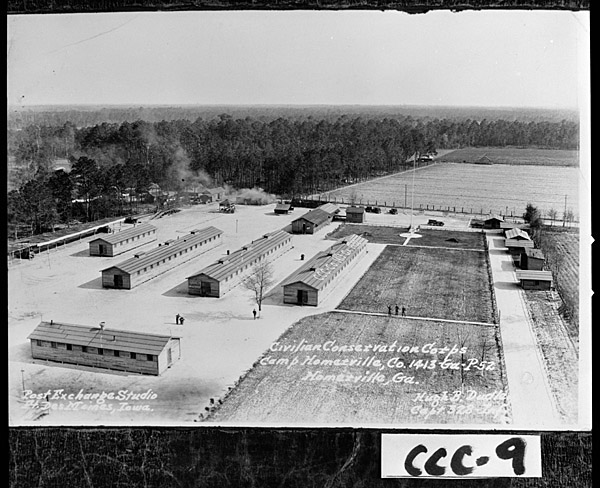

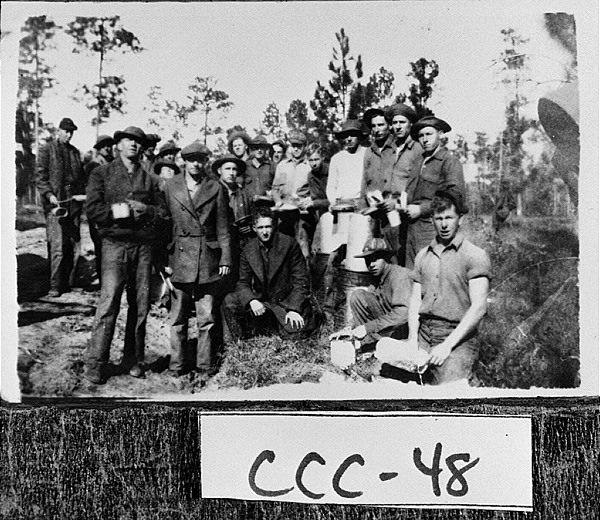

The New Deal’s Social Security program offered income support for the state’s work force, and the National Labor Relations Act (1935) facilitated the unionization of the state’s textile mills and factories and set minimum wages, working conditions, and working hours for industrial workers. Child labor, notoriously common in Georgia’s factories and mills, was eliminated entirely, while the school year was expanded to seven months, new schools were constructed, and textbooks were provided to students free of charge. The Rural Electrification Administration fostered cooperatives for the delivery of electricity to rural residents, and the Agricultural Adjustment Act gave farmers subsidies to limit overproduction of certain crops and drive up market prices. New Deal programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) helped put thousands of Georgians back to work.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

The impact of the New Deal on the state’s lowest-income population was mixed, however. Benefits for poor white farmers were minimal. Because of Georgia’s politics of white supremacy and the importance of its congressional delegation to Roosevelt’s programs, the federal government bowed to most of the state’s wishes to curtail benefits for Blacks. One important exception was the National Youth Administration, which brought work relief to the state’s rural Black poor.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

In the most far-reaching of all reforms, Georgia’s cash-crop agriculture, long tied to ever-less profitable cotton production, was broken by Roosevelt’s farm policies, which encouraged mechanization, soil improvement, pricing controls, diversification of crops, and hog, broiler, and dairy production. By the end of the depression decade the cotton plantation, the tenant farmer, and the small family farm began to fade—along with agriculture as the mainstay of Georgia’s economy. It took World War II to end the Great Depression in Georgia, but it was the New Deal that laid the foundation for a more balanced economy and secure standard of living.

Documenting the Depression in Fact and Fiction

The state’s greatest cataclysm since the Civil War (1861-65) attracted the attention of journalists, academics, memoirists, and novelists, who created a rich body of literature—fictional and nonfictional—about the depression era in Georgia. In the 1930s Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White traveled through Georgia documenting, through his words and her photographs, the bleak lives of the rural poor. Their collaboration resulted in the book You Have Seen Their Faces (1937). Under the auspices of the Farm Security Administration, other photographers, most notably Jack Delano, documented farm families in Georgia and elsewhere in the Deep South.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Arthur F. Raper made the plight of Georgia’s farmers, Black and white, the subject of several influential studies, including Preface to Peasantry, which focuses on Greene and Macon counties; Sharecroppers All (1941); and Tenants of the Almighty (1943), a follow-up to Preface to Peasantry, in which he examines the impact of New Deal efforts on the poverty he had documented several years earlier. A similar work that reached a far wider audience is Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), by writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans, who teamed up to document southern sharecropping and its effects. While the book’s primary focus is on three families in Alabama, conditions in Georgia are also well represented.

A major effort of the Federal Writers Project (FWP), a component of the WPA, was the creation of state guidebooks. The project employed out-of-work writers, artists, local historians, genealogists, folklorists, and librarians as researchers and writers. Georgia: The WPA Guide to Its Towns and Countryside was published in 1940 by the University of Georgia Press, and it provides a revealing portrait of the state’s social and economic situation in the late 1930s that serves almost as a journalistic time capsule. The FWP also conducted thousands of interviews with formerly enslaved individuals in Georgia and other southern states, supplying historians with an array of firsthand accounts not only of slavery and emancipation but also of Black life during the Great Depression. An outgrowth of that work is Drums and Shadows (1940), a unique oral history containing slave narratives that capture African American life and heritage on the coastal islands.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Robert E. Burns’s 1932 book I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! (made into a popular Hollywood film) added to the image of Georgia as a dark and backward place. John Spivak’s Georgia Nigger (1932) exposed the brutal treatment of Black prisoners in the state’s convict camps and presented the hopeless situation of the tenant farmer, hard-working yet doomed to poverty. Later autobiographies by Harry Crews, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978), and Jimmy Carter, An Hour before Daylight (2001), contain vivid childhood memories of rural life in south Georgia during the 1930s. In Ava’s Man (2001) Rick Bragg reconstructs, through the memories of various family members, his grandparents’ hardscrabble existence in Floyd County.

The Great Depression inspired a number of significant works of fiction as well, both during the era and long afterward. Samuel Tupper Jr., who worked as an editor and writer for the WPA guide, wrote the well-received novel Old Lady’s Shoes (1934), which provides an insider’s view of life in Atlanta during the depression. Milledgeville native Grace Lumpkin’s radical novels To Make My Bread (1932) and A Sign for Cain (1935) represent some of the best works of literary social realism produced in response to the depression.

The Pulitzer Prize–winning Lamb in His Bosom (1933), by Waycross native Caroline Miller, depicts Georgia’s rural pioneers before the Civil War. The antebellum story is an obvious parallel to the depression-era hardships involved in eking out a living on Georgia’s hard clay soil. Erskine Caldwell’s novels Tobacco Road (1932) and God’s Little Acre (1933) thrust the Coweta County native onto a national stage and quickly became the most popular depictions of southern rural poverty and degeneracy produced during the era or since. According to historian James Cobb, Caldwell’s books “became a symbol of the evils of the sharecropping system and the ills . . . endured by a worn-out people trying to live on worn-out soil.” Later fiction dealing with small-town life during the depression in Georgia includes novels by Terry Kay, Carson McCullers, Ferrol Sams, and Calder Willingham.

The Persistence of “An Open-Hearted and Optimistic Spirit”

The literary critic and essayist H. L. Mencken, based in Baltimore, Maryland, never tired of making the South a national spectacle. In his effort in 1931 to identify the “worst American state,” Georgia ranked near the bottom in wealth, education, health, and public security (a reference to lynching). And yet, the Great Depression in Georgia was not an era of unrelieved agony. About half of the state’s population remained gainfully employed, and in the tradition of the South’s spirit of hospitality, families and friends extended helping hands. In the countryside community networks offered a safety net for the most vulnerable; children were sent from farms to live with employed kin in cities, and people doubled up in their living space to make room for relatives out of work. The bounty of backyard gardens was shared with neighbors and hungry passersby, while barns became overnight shelters for the homeless.

Courtesy of Synovus

Factory managers and small business owners imparted charity when they could, and entrepreneurs like W. C. Bradley of Columbus operated his mills at a loss to avoid laying off workers. The head of the Coca-Cola Company, Robert Woodruff, established a foundation in 1937 that gave generously to charities in Atlanta and around the state.

What happened inside families and communities during the Great Depression was no less important than what happened in government offices and the U.S. Congress. According to one commentator, “The survival of an open-hearted and optimistic spirit may be the most remarkable legacy of these impoverished southerners.” Despite the relief and recovery efforts provided by New Deal policies, it would take the federal dollars that poured into the state during World War II—for military bases and defense contracts—to ultimately bring the nation’s worst economic crisis to an end.