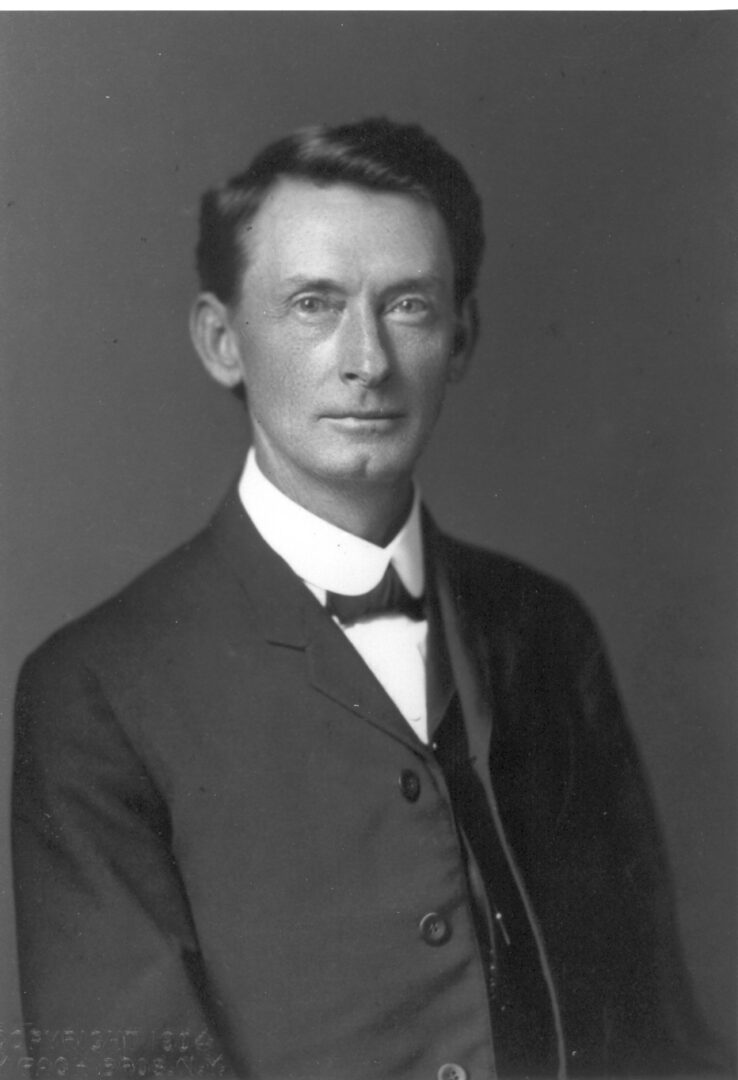

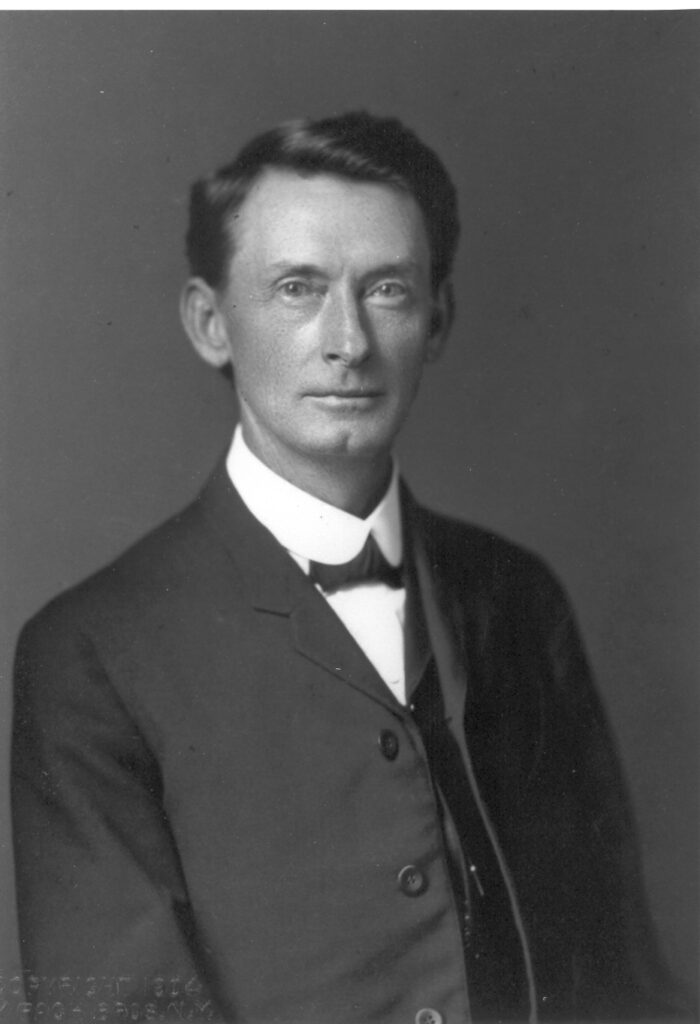

The public life of Thomas E. Watson is perhaps one of the more perplexing and controversial among Georgia politicians. In his early years he was characterized as a liberal, especially for his time. In later years he emerged as a force for white supremacy and anti-Catholic rhetoric. He was elected to the Georgia General Assembly (1882), the U.S. House of Representatives (1890), and the U.S. Senate (1920), where he served for only a short time before his death. Nominated by the Populist Party as its vice presidential candidate in 1896, he achieved national recognition for his egalitarian, agrarian agenda. Although his terms of elective office were short, for more than thirty years his support was essential for many men running for public office in Georgia. In addition to his political achievements, Tom Watson was a practicing lawyer, publisher, and historian. He is remembered for being a voice for Populism and the disenfranchised, and later in life, as a southern demagogue and bigot.

Family and Education

Born on September 5, 1856, on a plantation in Columbia County (the area today is part of McDuffie County), Edward Thomas Watson (later Thomas Edward Watson) understood the culture of the antebellum South. He was the second of seven children of Ann Eliza Maddox and John Smith Watson, both descendants of Quakers. He grew up on his grandfather’s plantation, near the town of Thomson. Watson’s primary education consisted of course work at a small school in Thomson. In 1872 he entered Mercer University, but family finances allowed him to stay for only two years. The Watsons lost the family plantation in 1873 in the midst of the general economic collapse of the Reconstruction South. Young Watson began reading law while teaching school in Screven County and passed the Georgia bar in 1875. In 1877 he settled into a law practice in Thomson. The following year he married Georgia Durham, and they had three children, John Durham, Agnes, and Louise.

Rise to Prominence

Although Watson quickly became one of the foremost trial lawyers in Georgia, he was drawn to local politics. Early in his legal career Watson had been influenced by many of the leaders of the Confederacy, including his boyhood heroes Robert Toombs and Alexander Stephens. During an era in which northern influences for capitalism over agrarianism were challenging regional traditions, Watson emerged as a voice for the agrarian tradition. He appealed to Georgians as a defender of the old way of life when he was first elected to the state legislature, representing McDuffie County, in 1882. Watson discovered that the support of the Black voting population was necessary to win. Once in office he supported the elimination of the state’s convict lease system, favored taxes to support public education, and championed the needs of poor farmers and sharecroppers of both races.

Watson did not remain in the legislature for long, however; he chose to resign his seat before the end of the session. His writings indicate that he was dissatisfied with the slow pace of the lawmaking process and resentful of the growing influence of the “New South” as it moved away from the traditional agrarian economy toward more industrial sectors.

The Farmers’ Alliance and Populism

As the New South emerged from the chaos of Reconstruction, so did discontent among farmers throughout the region. The Farmers’ Alliance organized to voice this resentment, and it was within that organization that Watson became a powerful leader, although he never formally joined the alliance. Issues at the forefront of the Farmers’ Alliance platform included the reclamation of large tracts of land granted to corporations, the abolition of national banks, an opposition to paper money, an end to speculation on farm commodities, and a decrease in taxes levied on low-income citizens. On this platform he campaigned and won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, representing Georgia’s Tenth District, in 1890. In Congress he pushed for legislation to enact various Alliance goals, and he was successful in endorsing an experimental program of bringing free delivery of mail to rural areas. Although Watson’s bill was not implemented immediately upon its passage in 1893, rural free delivery was gradually introduced in various regions around the country and was instituted nationwide in 1902. The U.S. Postal Service’s rural delivery system still serves more than 41 million customers today.

The Farmers’ Alliance itself was not well received by proponents of the New South. Atlanta Constitution managing editor Henry W. Grady and the powerful Bourbon Triumvirate, which included Joseph E. Brown, Alfred H. Colquitt, and John B. Gordon, opposed much of its platform. Watson presented the platform in terms of an idyllic pastoral country life contrasted with the evils of industrialization and urbanization. As these differences were publicized and his frustration with the indifference of Congress toward his legislative initiatives grew, Watson increasingly distanced himself from the mainstream of the Democratic Party.

In 1891 Watson refused to support the election of fellow Georgian Charles F. Crisp, a far more conservative Democrat than Watson, as Speaker of the House. By then, the Populist, or People’s, Party had evolved as the political organization of the Farmers’ Alliance, and Watson was nominated as its candidate for the speakership. Although he was widely criticized for abandoning the Democrats, he won a vast new following of farmers in Georgia and across the South. He also earned the support of many rural Black voters in his 1892 bid for reelection to Congress through his condemnation of lynching and his protection of a Black supporter from a lynch mob in the final days before the election. Nevertheless, he was narrowly defeated by his Democratic opponent. He was defeated again in 1894, and in both elections there was substantial evidence of election fraud and Black voter intimidation. These bitter losses increased divisions between the Democrats and the Populists.

In 1896 the Democratic Party nominated William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska as its presidential candidate, and Arthur Sewall, a banker, as its vice presidential candidate. Some Populists backed Bryan and believed fusing the Populist and Democratic tickets could be successful. Watson balked at fusing the tickets, but delegates to the Populist convention (which Watson did not attend) eventually convinced him to agree to compromise. In the end Watson, who had been led to believe his name would appear on the ticket instead of Sewall’s, was duped by the Democrats. The Republican candidate, William McKinley, won the election, and the Populist Party never recovered from the loss.

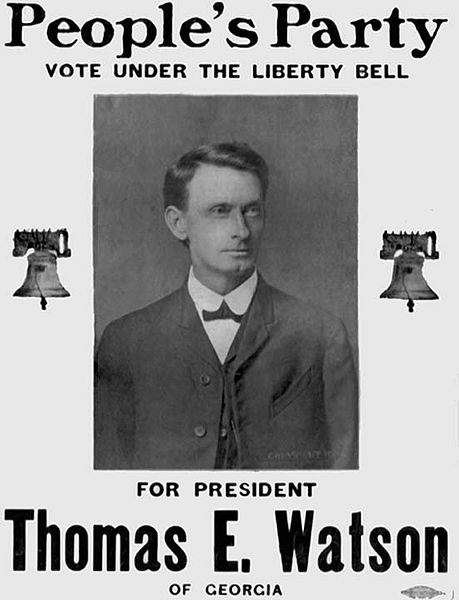

Watson temporarily withdrew from politics at this point and resumed his law practice in Thomson. Though he would reemerge to run for president as a Populist in 1904 and 1908, neither he nor the much-diminished party ever posed a serious threat to the Democrats or Republicans. Within Georgia, however, Watson continued to exert considerable political influence. In 1906 he helped Hoke Smith win the race for governor, and thereafter no serious candidate for governor could be considered without his endorsement.

Later Years

Soon after the turn of the century, Watson turned to writing at his newly acquired Hickory Hill estate on the outskirts of Thomson. He wrote a two-volume history of France (1899), followed by a novel, Bethany: A Story of the Old South (1904), and biographies of Napoleon (1902), Thomas Jefferson (1903), and Andrew Jackson (1912). Through his Jeffersonian Publishing Company, Watson also produced a magazine and a weekly newspaper that achieved widespread circulation throughout the South and in New York. Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine in particular became an outlet for lengthy editorials on anti-capitalistic political philosophies and for strong diatribes reflecting his increasing racial and religious bigotry.

Although Watson had long supported Black enfranchisement in Georgia and throughout the South, he changed his stance by 1904. Resentful of Democratic manipulation and exploitation of Black voters and strongly opposed to the increased visibility and influence of such leaders as W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, Watson endorsed the disenfranchisement of African American voters, and no longer defined Populism in racially inclusive terms. Watson supported Hoke Smith in the 1906 Georgia’s governor’s race only on the condition that Smith support Black disenfranchisement, and the inflammatory rhetoric that surrounded the issue was partially responsible for sparking the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906. Governor Smith later delivered on his promise to Watson by leading the successful adoption of a constitutional amendment that effectively disenfranchised Black Georgia voters. During his 1908 presidential bid Watson ran as a white supremacist and launched vehement diatribes in his magazine and newspaper against Black Americans.

Watson also launched an aggressive campaign against the Catholic Church. He took issue with the hierarchy of the church and railed against abuses by its leaders. He mistrusted the church’s foreign missions and its historic political activities. The Catholic Church responded by putting pressure on businesses that advertised in Watson’s publications, resulting in an effective boycott. In 1913, during the trial of Leo Frank, Watson’s strong attacks on Frank and on the pervasive influence of Jewish and northern interests in the state heavily influenced negative sentiment against Frank, who was lynched by a mob in 1915.

Watson continued to speak of oppressed working people, especially farmers, who were opposed by capitalists long after those ideals inspired political support. Although he shunned Socialism and worked to maintain Populism’s distinction from it, with the outbreak in 1914 of World War I in Europe, Watson grew increasingly sympathetic to the insurgent Socialist Party in the United States, and he supported its opposition to American entry into the European conflict. As a result of his Socialist association and his continued criticism of the war after the American entry in 1917, the U.S. Post Office refused to deliver the publications in which his attacks were published, thus bringing them to an end. In 1918 he made a late bid for Congress but lost to Carl Vinson, who had been a strong supporter of American involvement in the war.

In 1920 Watson entered his final political race and achieved his first success in more than two decades when he ran for the U.S. Senate, defeating the incumbent senator, Hoke Smith. On September 26, 1922, in the second year of his six-year term, Watson died suddenly. Governor Thomas Hardwick appointed eighty-seven-year-old Rebecca Latimer Felton as a temporary replacement, until Walter F. George was elected to finish the remainder of Watson’s term.

For decades an imposing statue of Watson, dedicated in 1932, stood on the grounds of the Georgia state capital. Controversy surrounding the statue led to its relocation in 2013 to a park across the street.