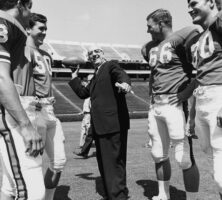

Richard B. Russell Jr. served in public office for fifty years as a state legislator, governor of Georgia, and U.S. senator. Although Russell was best known for his efforts to strengthen the national defense and to oppose civil rights legislation, he favored describing his role as advocate for the small farmer and for soil and water conservation. Russell also worked to bring economic opportunities to Georgia. He helped to secure or maintain fifteen military installations; more than twenty-five research facilities, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Russell Agricultural Research Center; and federal funding for development and construction. Russell believed that his most important legislative contribution was his authorship and secured passage of the National School Lunch Program in 1946.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Serving in the U.S. Senate from 1933 until his death in 1971, Russell was one of that body’s most respected members. Secretary of State Dean Rusk called him the most powerful and influential man in Washington, D.C., for a period of about twenty years, second only to the president. Russell attained that position of power through his committee assignments—specifically a total of sixteen years as the chair of the Armed Services Committee and a career-long position on the Appropriations Committee, serving as its chair for his last two years in the Senate. In large measure he determined the agricultural and defense legislation considered by the Senate, as well as matters affecting the federal budget. During the twentieth century Russell, along with Carl Vinson in the U.S. House of Representatives, was undeniably among the nation’s foremost experts on military and defense policy. An advisor to six presidents and a 1952 candidate for president, Russell ended his career as president pro tempore of the Senate, making him third in the line of presidential succession.

Early Life

Richard Brevard Russell Jr. was born in Winder on November 2, 1897, to Richard B. Russell Sr., a lawyer, state legislator, businessman, and judge, and Ina Dillard Russell, a teacher. He was the fourth child, and first son, of what became a family of thirteen children. Russell was related to Marietta’s Brumby family through his paternal grandmother, Rebecca Harriette Brumby, and in the 1950s his cousin, Otis A. Brumby Jr., worked for him as a Senate page.

His education began at home, where a governess taught Russell and his siblings until 1910. In 1911-13 and again in 1915 he attended the Gordon Institute in Barnesville, and he graduated in 1914 from the Seventh District Agricultural and Mechanical School (later John McEachern High School) in Powder Springs (Cobb County). In 1915 he entered the University of Georgia and was active in various social groups, including the Sigma Alpha Epsilon social fraternity, the Gridiron Club, the Jeffersonian Law Society, and the Phi Kappa Literary Society. He graduated in 1918 with a Bachelor of Laws degree.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

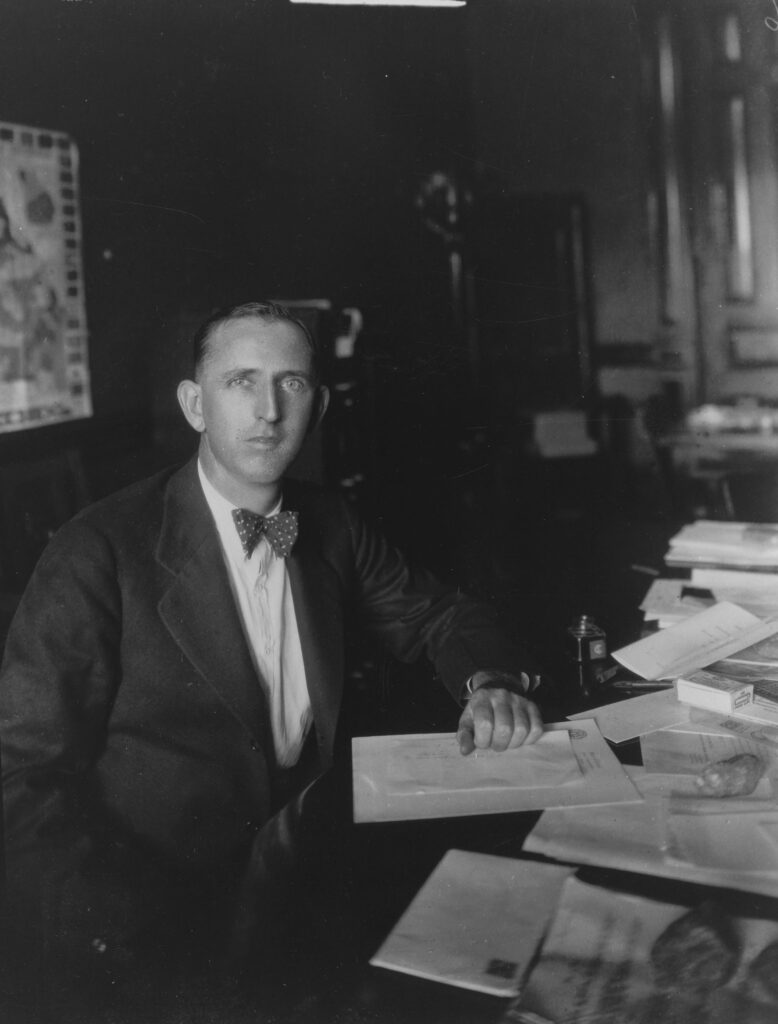

Early Political Career

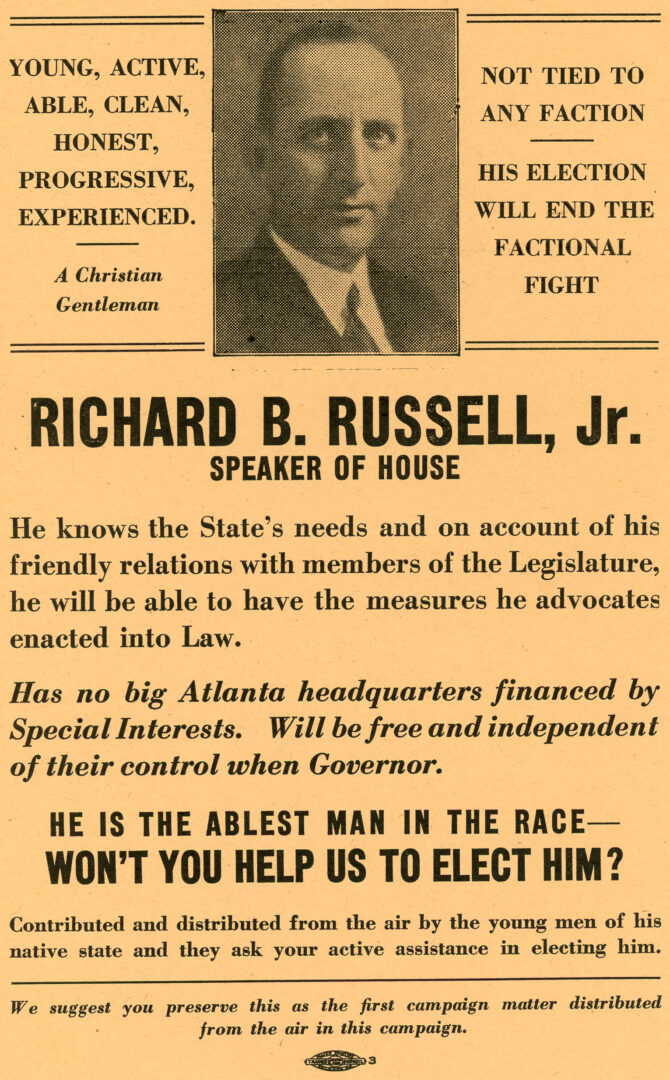

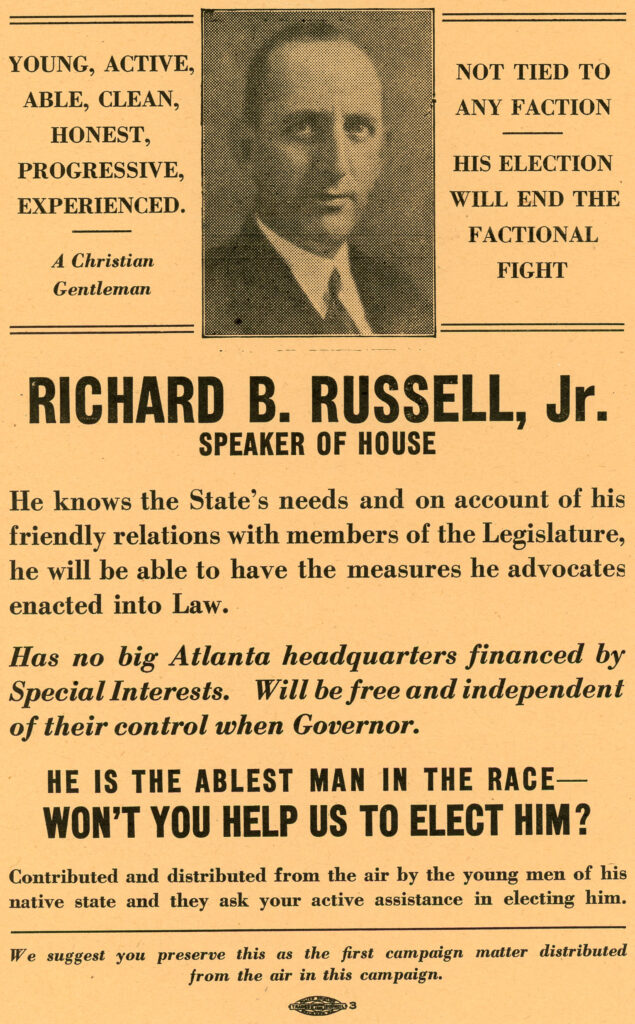

After practicing law for more than a year, Russell was elected in 1920 to the Georgia House of Representatives, becoming at age twenty-three one of the youngest members of that body. He received appointments to various committees and, building on friendships from his school days, advanced quickly in the political arena. He was elected Speaker pro tempore by the state house in 1923 and 1925. In 1927 he was elected Speaker of the House and remained in that position until 1931.

In the state legislature Russell advocated building and improving highways, supported public education, and called for reducing the control of special-interest groups in order to develop a fiscally responsible and efficient state government. He took the same agenda to the people in April 1930, when he announced his candidacy for governor. Russell battled a field of seasoned candidates to win the gubernatorial election. His victory was attributed to a grassroots campaign and his skill in canvassing voters door-to-door across Georgia.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Becoming Georgia’s youngest governor in the twentieth century, Russell took the oath of office in June 1931. During his eighteen-month tenure, his most significant achievement was a comprehensive reorganization of the state government, which was accomplished by reducing the number of agencies from 102 to 17. A highlight of this reorganization was the creation of the University System of Georgia, with the Board of Regents as the single governing body over all state colleges and universities. Russell cut state expenditures by 20 percent, balanced the budget without cutting salaries (other than his own), and honored $2.8 million in delinquent obligations.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

The death of U.S. senator William J. Harris in 1932 opened the door for Russell to enter national politics. On April 25 Governor Russell appointed John S. Cohen, publisher of the Atlanta Journal, as interim senator and announced his own candidacy for election to Harris’s unexpired term, which ran until 1937. After a tough campaign, Russell was victorious against Charles Crisp, a veteran congressman. Russell’s only other contested U.S. Senate election occurred in 1936, when he defeated Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

U.S. Senate

Russell entered the U.S. Senate in 1933 as the youngest member and a strong supporter of U.S. presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt. Seeing the New York governor as the leader who could end the Great Depression, Russell had detoured from his own campaign to attend the Democratic National Convention and to make a seconding speech for Roosevelt’s nomination. The two men had become acquainted during the 1920s, when Roosevelt often visited Warm Springs. After Roosevelt was elected president, Russell marked his first decade in the Senate by ensuring the passage of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Russell was awarded an unheard-of freshman spot on the important Appropriations Committee, and he became chairman of its subcommittee on agriculture, a post he retained throughout his career. Russell deeply believed in the significance of agriculture in American society. Representing a mostly rural Georgia, he focused on legislation to assist the small farmer, including the Farm Security Administration, the Farmers Home Administration, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Rural Electrification Act, the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Resettlement Administration, commodity price supports, and soil conservation. A major participant in the Farm Bloc, he worked with a bipartisan group of senators who were committed to increasing the success rate for individual farmers.

In 1933 Russell was appointed to the Naval Affairs Committee, and he continued to serve when that committee and the Military Affairs Committee were reorganized in 1946 to form the Armed Services Committee. Russell served on the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, the Central Intelligence Agency’s congressional oversight committee, and the Aeronautical and Space Sciences Committee, as well as on the Democratic Policy and Democratic Steering committees from their inceptions. After World War II (1941-45), Russell’s seniority and strong committee assignments, following a congressional reorganization, placed him in key power positions both legislatively and politically.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Civil Rights

Russell began contesting civil rights legislation as early as 1935, when an antilynching bill was introduced in Congress. By 1938 he led the Southern Bloc in resisting such federal legislation based on the unconstitutionality of its provisions. The Southern Bloc argued that these provisions were infringements on states’ rights. By continually blocking passage of a cloture rule in the Senate, Russell preserved unlimited debate as a method for halting or weakening civil rights legislation. Over the next three decades, through filibuster and Russell’s command of the Senate’s parliamentary rules and precedents, the Southern Bloc stymied all civil rights legislation.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

By 1964, however, American society and the U.S. Senate itself had changed dramatically, and the strongest civil rights bill up to that time passed overwhelmingly. Once the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law, Russell urged compliance and counseled against any violence or forcible resistance; he was the only opponent of the bill to do so.

Russell was a defender of white southern traditions and values. Much of his opposition to civil rights legislation stemmed from his belief that “South haters” were its primary supporters and that life and culture in the South would be forever changed. He believed in white supremacy and a separate but equal society, but he did not promote hatred or acts of violence in order to defend these beliefs. His arguments for maintaining segregation were drawn as much from constitutional beliefs in a Jeffersonian government that both emphasizes a division of federal and state powers and fosters personal and economic freedom as they were from notions of race.

Russell’s stand on civil rights was costly to the nation and to Russell himself. It contributed to his defeat in a bid for the presidency, often diverted him from other legislative and appointed business, limited his ability to accept change, weakened his health, and tainted his record historically.

Military Affairs

During World War II Russell led a special committee of five senators around the world to visit the war theaters and to report on the status of American troops. He expanded his views on national defense during this time to include strategic international bases for ensuring security and maintaining world stability. At the same time he did not abandon his isolationism, for he was not eager to place America in the role of world policeman. Neither Russell nor his father supported United Nations membership. Russell also had little faith in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as a peacekeeping force, and he was concerned that American-supplied arms to an allied country would fall into the hands of an aggressor. After 1945 Russell agreed with very little American foreign policy. Specifically, he opposed large foreign-aid expenditures when they caused a budget deficit for defense. He believed America’s best defense was a military power so strong that no other nation could challenge it successfully.

In 1951 U.S. president Harry Truman removed General Douglas MacArthur as commander in the Far East. As chair of the joint Senate committee investigating MacArthur’s dismissal, Russell conducted hearings that set the model for congressional inquiry. Many national newspapers praised Russell for his skill in defusing the situation, and he gained a reputation as one of the most powerful men in the Senate.

As the United States and the Soviet Union squared off, Russell strongly supported a military buildup, for which he insisted on civilian oversight or control. As chair of the Armed Services Committee, he started its Military Preparedness Subcommittee. He was a leader in establishing the Atomic Energy Commission, in setting up an independent Central Intelligence Agency, and in placing space exploration and development in the hands of both civilians and the military.

In 1954 Russell spoke against American military support of the French in Vietnam. A stalwart nationalist, he favored military force only when America’s interests were directly threatened. He reiterated this sentiment in 1967, when the Johnson administration sent cargo planes to the Congo. Russell fought against rapid deployment, believing that the United States would always find reason to intervene in other nations’ conflicts once its military had the ability to engage quickly in some far-flung battle. On June 25, 1969, the Senate passed the National Commitments Resolution, which Russell, along with Senator J. W. Fulbright, was instrumental in drafting. The resolution reasserted the Senate’s right to be a participant in the making of commitments by the United States.

Photograph by Abbie Rowe, National Park Service. Courtesy of Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, National Archives and Records Administration

As the Johnson administration escalated the war in Vietnam, Russell still could not see a prevailing reason for America’s involvement. During the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, he had advocated military action in what he saw as a direct Communist threat to the nation. Upholding the Monroe Doctrine, in this case, was of vital interest to the nation and its hemisphere. With Vietnam, Russell, who believed deeply in the presidency, found himself supporting four administrations as America descended into the quagmire. While he advised the presidents to “go in and win—or get out,” he could neither prevail with full-scale military power nor find diplomatic solutions. Once the flag was committed, however, so was Russell. Though frustrated by policy and critical of war tactics, he did all he could to support U.S. troops by assuring that they had the best equipment and supplies and by monitoring defense appropriations.

Leadership

Pursued by colleagues to accept the Senate majority leadership, Russell steadfastly refused because he wanted “absolute independence of thought and action.” Instead, he promoted his young protégé Lyndon Johnson, who became the majority whip and, later, the majority leader. This was the beginning of Johnson’s rise to power, and he would not have succeeded so quickly without Russell’s favor.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Russell’s name was twice put forward for nomination as the Democratic candidate for president. Although not a formal candidate in 1948 and not in attendance at the convention, he received 263 votes from 10 southern states that were looking for an alternative to Truman and his civil rights platform. Russell refused to join the Dixiecrats, who subsequently broke away from the party to form their own slate. In 1952 he announced his candidacy and went on to win the Florida primary. His agenda included a strong statement for local and states’ rights against a growing federal centralization. At the convention he received a high of 294 votes from 23 states and lost on the third ballot to Adlai Stevenson.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

In 1963 U.S. president Lyndon Johnson appointed a reluctant Russell to the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy, or the Warren Commission, as it came to be known. Russell rejected the single-bullet theory, as did Texas governor John Connally, who had been wounded in the attack on Kennedy. Thinking “so much possible evidence was beyond [the commission’s] reach,” Russell insisted that Earl Warren qualify the commission’s findings to read that they found “no evidence” that Oswald “was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign.” Compromise with Russell was the only way Warren obtained a unanimous report.

Russell’s Legacy

Russell devoted his life to public service. His love of the Senate and its traditions was most evident in his own example of conduct and leadership. Russell earned the respect and admiration of his most ardent opponents for his integrity, intellect, modesty, and fairness.

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Although he never married, Russell dated regularly over the years. In 1938 his engagement to an attorney ended because the couple could not reconcile differences over her Catholic faith; he later wrote that the failed relationship was his one regret. Throughout his life, Russell set his course to follow the direction of Russell Sr., who told his seven sons that although not all of them could be brilliant or successful, they could all be honorable. Russell died of complications from emphysema at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C., on January 21, 1971. He lay in state at the Georgia state capitol, where U.S. president Richard Nixon visited to pay his respects.

Photograph by Larry Lamsa

The following year Russell’s colleagues passed Senate Resolution 296 naming his old office building the Richard Brevard Russell Senate Office Building. Subsequently, a nuclear-powered submarine, a federal courthouse in Atlanta, a state highway, a dam and lake, and various structures would bear his name. Russell is buried in his family’s cemetery behind the Russell home in Winder.