Founded in 1733 by colonists led by James Edward Oglethorpe, Savannah is the oldest city in Georgia and one of the outstanding examples of eighteenth-century town planning in North America.

Colonial and Revolutionary Eras

Savannah was, by design, the first step in the creation of Georgia, which received its charter from King George II in April 1732, as the thirteenth and last of England’s American colonies. In November 1732 Oglethorpe, with 114 colonists, sailed from England on the Anne. This first group of settlers landed at the site of the planned town, then known as Yamacraw Bluff, on the Savannah River approximately fifteen miles inland from the Atlantic Ocean, on February 12, 1733.

After establishing cordial relations with Chief Tomochichi of the resident Yamacraw Indians, and Indian trader and liaison Mary Musgrove, Oglethorpe began to carry out his concept for the layout of Savannah. Oglethorpe and Savannah’s coplanner, William Bull of South Carolina, laid out a town loosely based on the London town model but featuring wards built around central squares, with trust lots on the east and west sides of the squares for public buildings and churches, and tything lots for the settlers’ homes on the north and south sides of the squares.

Oglethorpe and the Georgia Trustees originally conceived Savannah, and the new colony, as a philanthropic endeavor. It was the Trustees’ intention to provide a refuge for English debtors who could establish the basis for an agrarian class of small, yeoman farmers working in concert with a business and mercantile class in Savannah, thus providing a commercial outpost to the neighboring colony of South Carolina. In Savannah’s formative years, and through most of Georgia’s period as a proprietary colony, there was a ban on slavery. This ban was lifted in 1750. There were additional prohibitions in the new colony on “spirituous liquors” (until 1742), and Catholics were forbidden to live in the colony until the territorial and commercial disputes in the region between England and Spain were settled in 1748. There were no lawyers until 1755.

The early history of Savannah is remarkable for the sheer diversity of its people. Religious observance played an important role in the early life of Savannah. In addition to its founding English settlers, Jews arrived from London in the summer of 1733; they later founded the Congregation Mickve Israel, the oldest Jewish congregation in the South. In the spring of 1734 came Evangelical Lutherans from Salzburg, known as Salzburgers, who settled on the Savannah River at a town they named Ebenezer. Scottish Highlanders and German Moravians came in 1736, followed by Dutch, Welsh, and Irish settlers. John Wesley and Charles Wesley conducted Anglican services. In 1737 the Reverend George Whitefield arrived and soon after founded Bethesda, colonial America’s first orphanage.

Savannah citizens played prominent roles in the cause of American independence, although Georgia, as a general rule, was somewhat slower than the other British colonies to embrace the Revolutionary fervor sweeping the rest of the Atlantic seaboard. The Liberty Boys, a group of Savannah men prominent in the independence movement, met periodically at Peter Tondee’s Tavern, at the corner of Broughton and Whitaker streets. Three men who lived or maintained professional connections in Savannah were Georgia’s signers of the Declaration of Independence—Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, and George Walton.

British forces captured Savannah in 1778 and reinstalled James Wright as colonial governor of Georgia. In October 1779 a combined force of Americans and Frenchmen, commanded by General Benjamin Lincoln and Count Charles Henri d’Estaing, attempted to retake Savannah from its British occupiers. The allied army sustained heavy casualties and was repulsed on the outskirts of Savannah by British defenders led by Colonel John Maitland and the Seventy-first Highlanders. From this encounter, regarded as one of the bloodiest battles of the American Revolution (1775-83), emerged two of Savannah’s most notable military heroes, Sergeant William Jasper and Count Casimir Pulaski, both of whom were killed during the unsuccessful assault on the British lines.

After the Revolution, Savannah was the first capital of Georgia, relinquishing that role to Augusta in 1786. President George Washington visited Savannah in 1791. During his stay he called on Catharine Greene of nearby Mulberry Grove plantation. She was the widow of General Nathanael Greene, commander of the Continental army in the southern theater, who had been awarded Mulberry Grove in recognition of his services to the cause of independence. A monument to Greene was dedicated in Savannah in 1825 by another famous Revolutionary hero, the Marquis de Lafayette, during a visit to the city that year. It was at Mulberry Grove plantation in 1793 that Eli Whitney, a tutor to the Greene children, perfected the first working cotton gin suitable to combing seeds from short-staple (upland) cotton.

Antebellum Period

Antebellum Savannah was built around slavery and agriculture, primarily the chief money crops of cotton and rice, and was one of the leading cotton-shipping ports in the world. By 1820 Savannah was the eighteenth largest city in the United States and had established its preeminence as an international shipping center, with exports exceeding $14 million. Cotton remained the principal export until the Civil War (1861-65), when it made up 80 percent of the agricultural products shipped from Savannah.

The S.S. Savannah, the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean from the United States to Europe, sailed from Savannah in May 1819, arriving at Liverpool in twenty-nine days. In 1833 the Central of Georgia Railway (originally the Central Railroad and Canal Company of Georgia), in which the city of Savannah was the largest stockholder, received its charter from the Georgia legislature. This line, from Savannah to Macon, was completed in 1843, allowing more cotton to be shipped from the interior of the state to the coast.

Savannah, like many coastal cities in the nineteenth century, suffered its share of cataclysmic disasters associated with fire, water, and disease. Destructive fires in 1796 and 1820, both particularly damaging to the commercial districts, left about half the city in ruins. A major hurricane in September 1854 flooded the local rice and cotton plantations and greatly injured the port and shipping in the area. The already difficult years of 1820 and 1854 were made disastrous by severe yellow fever epidemics. More than 700 people died of yellow fever in 1820, and slightly more than 1,000 perished from the disease in 1854.

The census of 1860 certified Savannah as Georgia’s largest city (a distinction it had held since the birth of the colony), with 14,580 free inhabitants, including 705 free Blacks, and 7,712 enslaved African Americans. By the time of the Civil War, Savannah’s free Black population was among the most entrepreneurial in the South, with established interests in small businesses, agriculture, land ownership and, in some cases, even slave ownership. By this time Savannah was regarded as one of the most beautiful and tranquil cities in America, particularly after Forsyth Park was laid out in 1851.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Fort Pulaski, on Cockspur Island at the mouth of the Savannah River, was constructed between 1829 and 1847 (Robert E. Lee, as a young West Point graduate, oversaw some of the early phases of construction). In early 1861, three months before the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Confederate forces seized Fort Pulaski. The brick masonry fortification was considered impregnable until it was forced to surrender in April 1862 to Union forces using rifled artillery, a new technology in siege warfare. For the remainder of the war, Savannah was blockaded from its seaward side, and conditions for the city’s civilian population became extremely difficult.

Savannah fell to Union general William T. Sherman at the end of his army’s march to the sea from Atlanta. On December 22, 1864, Sherman transmitted his famous telegram to U.S. president Abraham Lincoln in which he presented “as a Christmas gift, the City of Savannah with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition; and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

After being spared destruction from Sherman’s forces, Savannah struggled through the chaotic years of Reconstruction. The city’s population swelled with the influx of thousands of freedpeople following the Civil War. The majority of Savannah’s new Black citizens lived in squalid conditions and were subjected to exorbitant rents and prices for goods by resentful whites. Two separate social cultures evolved for Blacks and whites, and distinct racial lines were drawn, particularly in education. Teachers from the North came to Savannah to provide education for Blacks, but progress was slow; it was not until 1878 that a public school for Blacks was established. In 1890 Georgia’s first public institution for higher learning for Blacks, Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth, was established in the city. In 1936 the school became Georgia State College, then Savannah State College in 1950, and Savannah State University in 1996.

By the early 1870s, Savannah had once again achieved commercial prosperity through its export of inland-grown Georgia cotton. From the 1880s until the 1920s Savannah was the world’s leading exporter of naval stores products, including pine timber, rosin, and distilled turpentine. By 1905 Savannah’s exports, chiefly cotton and naval stores, were greater than the combined exports of all other south Atlantic seaports.

Twentieth Century

In the 1920s the southern cotton industry was devastated by the boll weevil, and Savannah port activities turned to new industries to fill the void. Savannah became a national leader in the paper-pulp and food-processing industries with the opening of large-scale operations at Union Bag (which merged with Camp Paper in 1956) and the Savannah Sugar Refinery (Dixie Crystals) in the 1930s. Savannah’s port facilities also played a prominent role in World War II (1941-45). It was one of the nation’s most active Atlantic shipyards for the construction of Liberty Ship transports for the U.S. war effort. In the late 1940s, the Georgia Ports Authority acquired acreage on the Savannah waterfront at Garden City, and port operations began a period of rapid expansion.

The development of Hunter Army Airfield within the city, along with the sprawling training base at nearby Fort Stewart, enhanced Savannah’s growing reputation as a military town. These bases, with the shipping facilities of the port, enabled Savannah to play an important logistical role in the successful projection of U.S. military power during the Persian Gulf War (1990-91).

In the 1950s and 1960s, Savannah played a central role in the civil rights movement. The Savannah effort developed around a strategy of nonviolent protest implemented by local African American citizens. Ralph Mark Gilbert, a leader in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1940s and 1950s, is regarded as the father of the Savannah civil rights campaign. Gilbert launched a massive voter-registration drive for Savannah’s Black residents and led the way in 1947 for the integration of local law enforcement—the Savannah police department was one of the first in the Deep South to hire African American officers. Another important Savannah civil rights leader was W. W. Law, a longtime activist and visionary who headed the local NAACP branch. The Savannah civil rights effort during this period was a training ground for key NAACP leaders, including Hosea Williams, Earl T. Shinhoster, Mercedes Arnold, and Carolyn Q. Coleman.

The expansion of streetcar suburbs south of Victory Drive after World War I (1917-18) signaled Savannah’s first significant growth outward from the city’s historic and Victorian districts. By the early 1960s, the city had attained most of its present area of sixty-five square miles with the development of the suburban midtown and southside commercial and residential sections—areas that remain under development in the twenty-first century.

According to the 2020 U.S. census, Savannah, the seat of government of Chatham County, has a population of 147,780, with 404,798 persons in a three-county metropolitan area (Bryan, Chatham, and Effingham counties). The Port of Savannah is a bustling container-cargo center with a thriving international trade. Savannah is regularly ranked among the top five busiest container-shipping ports and the top ten busiest seaports in the United States, with continually expanding berthing, storage, and loading facilities. A record 10.1 million tons of cargo were processed by the port in the 2001 fiscal year.

Savannah continues to be a national leader in the processing of paper pulp and related products through International Paper Corporation (formerly Union Camp) and is also the home of Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation, one of the world’s leading manufacturers of corporate aircraft. Tourism has become the city’s leading industry.

During the twentieth century, several new colleges opened their doors in Savannah. In 1929 the Opportunity School, known today as Savannah Technical College , was established by the Savannah Chamber of Commerce and the city’s public school system. Armstrong State University, which was founded in 1935 as a junior college, is today a growing unit of the University System of Georgia and offers both undergraduate and graduate degree programs. The Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) was founded in 1979 and by 2004 had become the largest school of art and design in the United States. Students and faculty from SCAD have been instrumental in many of the historic preservation efforts around the city.

Historic Preservation and Tourism

Savannah, not surprisingly, is uniquely in touch with its extensive, varied history and has long been a center of historical research and preservation. Toward this end, in December 1839 the Georgia legislature chartered the Georgia Historical Society, which was founded earlier that year by three Savannah residents. The society has been headquartered in Hodgson Hall, located at the northwest corner of Forsyth Park, since 1875.

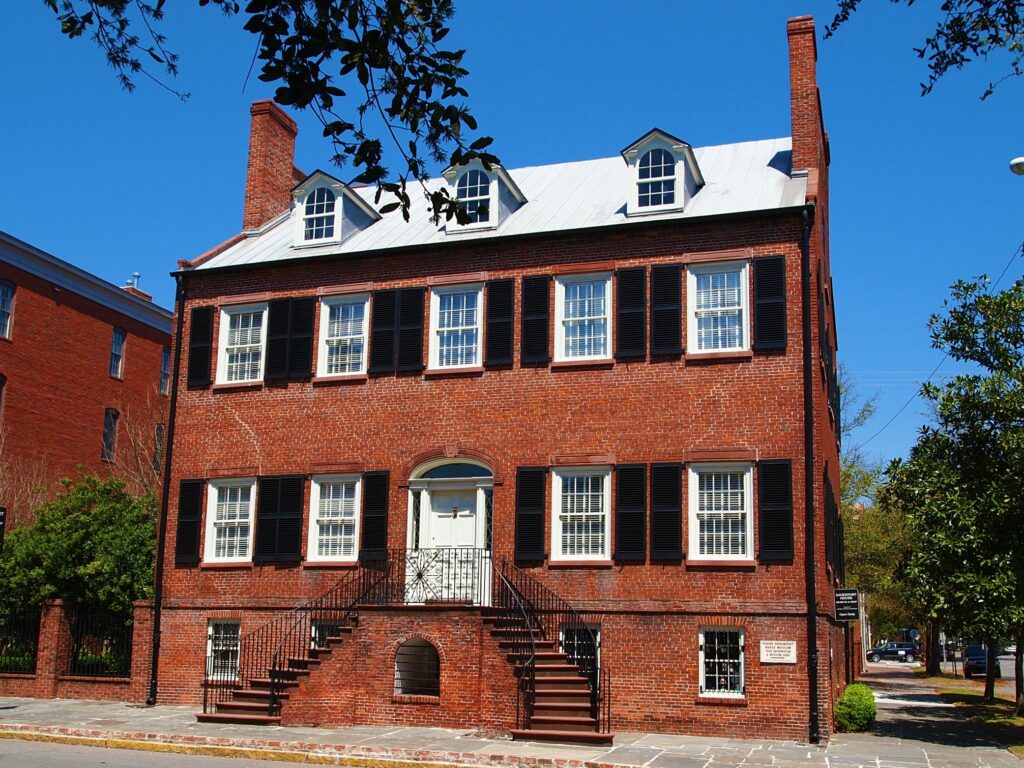

In the early 1950s, Savannah had a reputation as the “pretty woman with a dirty face.” Soon afterward, citizens launched a concerted preservation effort that ultimately attracted national attention. In 1955 eight leading women of Savannah society, led by Anna C. Hunter, saved the 1820 Davenport House from destruction. One of the lasting results of this effort was the Historic Savannah Foundation, which, over the last five decades, has saved many of the city’s old buildings in the historic district. The district was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966, and it remains one of the largest community urban-preservation programs of its kind in America. In May 2005 the historic Lincoln Street community received a $45,000 grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The grant was awarded to help prevent the economic displacement of residents from the neighborhood as renovated properties increase in value.

During the 1990s more than 50 million people visited Savannah, attracted by the city’s historic district, cultural amenities, and natural beauty, and by John Berendt’s New York Times best-seller, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, the movie version of which was filmed in Savannah. Many movies have been filmed in Savannah since the 1970s, including The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000), Forrest Gump (1993), Glory (1989), and Roots (1976).

Present-day visitors enjoy Savannah’s elegant architecture and historic ironwork featured in such structures as the birthplace of Juliette Gordon Low, founder of the Girl Scouts of the United States of America; Telfair Museums, one of the South’s first public museums; the First African Baptist Church, one of the oldest Black Baptist congregations in the United States; Congregation Mickve Israel, the third oldest synagogue in America; and the Central of Georgia Railway roundhouse complex, the oldest standing antebellum rail facility in America.

Other significant structures include the Owens-Thomas House and Slave Quarters, which, with the Telfair Academy, is a prime example of Regency architecture attributed to the English designer William Jay from the period 1818-25; the Pirates House (1754), the old seaman’s lodge mentioned in Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Treasure Island; the Pink House (1789), site of the first bank in Georgia; the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist (1876); the Independent Presbyterian Church (1890); and the former Wage Earners Savings and Loan Bank building (1914), once one of the largest African American banks in the United States and which now houses the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum.

Another interesting site for visitors is the Bamboo Farm and Coastal Gardens, which features more than 140 varieties of bamboo. Operated by the University of Georgia’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, the center conducts research, primarily on ornamentals and turf, and provides education for the public.