In many ways Georgia’s history is integrally linked to that of the rest of the South and the rest of the nation. But as the largest state east of the Mississippi, the youngest and southernmost of the thirteen colonies, and by 1860 the most populous southern state, Georgia is in certain respects historically distinctive.

Prehistory and European Exploration

The human history of Georgia begins well before the founding of the colony, with Native American cultures that date back to the Paleoindian Period at the end of the Ice Age, nearly 13,000 years ago. The Clovis culture, identified by its unique projectile points, is the earliest documented group to have lived in present-day Georgia. The more permanent settlements of the Late Archaic Period, including the notable population center at Stallings Island in the Savannah River, date back to 3000 B.C. During the Woodland Period, from around 1000 B.C. to A.D. 900, Native American groups in Georgia became increasingly sedentary, establishing villages and developing horticulture. Rock mounds and structures built during this era are found throughout the state, including the Kolomoki Mounds in Early County. Dating to around A.D. 500, these mounds are the remains of one of the most populous Woodland settlements north of Mexico.

Soon thereafter, for the roughly eight centuries of the Mississippian Period (A.D. 800-1600), complex native cultures, organized as chiefdoms, emerged and developed lifeways in response to the particular features of their physical surroundings. Georgia occupies a unique position both geographically and geologically, encompassing the Blue Ridge Mountains as well as two different coastal plains, those of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. These unique environmental zones drew a variety of native peoples to the region, leading to a greater diversity of early Indian cultures than was found elsewhere in the Southeast. The numerous varieties of pottery found in Georgia today testify to this diversity.

Towns with defensive structures were built during this period, as were numerous mounds, including those still evident today at Etowah, Ocmulgee, and Nacoochee. With the arrival of European explorers and settlers, the Mississippian cultures began to decline, and remnants of various chiefdoms coalesced to form larger societies, including those of the Creeks and Cherokees, both of which played significant roles in the colonial history of Georgia.

The earliest Europeans in North America, the Spanish, never established any permanent settlements within the region that would become Georgia, as they did in Florida and along the Gulf Coast. Their only attempt to do so, during a naval expedition led by Lúcas Vázquez de Ayllón in 1526, lasted only six weeks. Spanish expeditions moved through the region from the mid-1500s through the 1660s, the most notable of which was Hernando de Soto’s expedition in 1540. His party’s documentation of various Indian chiefdoms provides some of the best descriptions of native life in Georgia prior to the eighteenth century. The Spanish presence also included Catholic missionaries, who established Santa Catalina de Guale and other short-lived missions at points along Georgia’s coast from 1568 through 1684. These missions played a key role in assimilating the Native American populations of the region into the colonial system.

By the mid-1600s English settlers from South Carolina made forays across the Savannah River and into northeast Georgia, engaging first in a thriving slave trade of Indians and later in the even more lucrative deerskin trade, which continued well beyond the British colonization of Georgia.

Colonial and Revolutionary Georgia

Georgia’s colonial experience was very different from that of the other British colonies in North America. Established in 1732, with settlement in Savannah in 1733, Georgia was the last of the thirteen colonies to be founded. Its formation came a half-century after the twelfth British colony, Pennsylvania, was chartered (in 1681) and seventy years after South Carolina’s founding (in 1663). Georgia was the only colony founded and ruled by a Board of Trustees, which was based in London, England, with no governor or governing body within the colony itself for the first two decades of its existence. Perhaps most striking, Georgia was the only one of the North American colonies in which slavery was explicitly banned at the outset, along with rum, lawyers, and Catholics. (Jews did not receive explicit permission from the Trustees to join the colony but were allowed to stay upon their arrival in 1733.) Rum was eventually legalized in 1742 and slavery in 1751, marking the weakening of Trustee rule. The colony was governed by royally appointed governors instead of a council of Trustees from 1752 to 1776, ending with the outbreak of the Revolutionary War (1775-83).

The initial impetus behind Georgia’s founding came from James Oglethorpe, who envisioned the new colony as a refuge for the debtors who crowded London prisons; however, no such prisoners were among the initial settlers. Military concerns were a far more motivating force for the British government, which wanted Georgia (named for King George II) as a buffer zone to protect South Carolina and its other southern colonies against incursions from Florida by the Spanish, Britain’s greatest rival for North American territory. As a result, a series of fortifications was built along the coast, and on several occasions, most notably the Battle of Bloody Marsh on St. Simons Island, British troops that were commanded and financed by Oglethorpe kept the Spanish at bay.

As the colony with the shortest colonial experience, smallest population, and least development, Georgia remained largely on the periphery of Revolutionary War politics and wartime action. Though Georgians resisted British trade regulation, they tended to sympathize with British interests because royal rule had brought prosperity for many colonists and because they desired the presence of British troops to stem the threat of Indian attacks.

The colony, and then the state, was well represented at the Second Continental Congress (1775-81) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with three Georgians—Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, and George Walton —signing the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. In 1787 two Georgians, Abraham Baldwin and William Few Jr., signed the new U.S. Constitution at the Constitutional Convention, also in Philadelphia, and Georgia became the fourth state (following Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey) to enter the Union when it ratified the Constitution on January 2, 1788.

While Georgia saw several backcountry skirmishes as well as some attempted incursions into Florida, the Siege of Savannah in 1779 was the most serious military confrontation between British and American troops, as the latter, with help from French forces, tried unsuccessfully to liberate the city from its yearlong occupation by British troops. That same year, the capital was moved from Savannah to Augusta (Georgia’s second oldest city), and not long after, the Battle of Kettle Creek took place in nearby Wilkes County. Possibly present at Kettle Creek was legendary Georgian Nancy Hart, a female patriot and spy credited with killing several Tories at her home.

After the Trustees lifted the ban on slavery in the colony, Georgians moved quickly to establish a coastal plantation economy based on rice and Sea Island cotton. It was in Georgia that perhaps the most fateful development for the future of American slavery and the southern economy occurred in 1793, with Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin during a visit to the plantation of Catharine Greene, the widow of military leader Nathanael Greene. That invention quickly led to the development of the Black Belt region, a wide geographical swath with a pronounced concentration of enslaved African Americans and cotton cultivation. This belt spread from South Carolina through Alabama, Mississippi, and beyond, and included much of central and southwestern Georgia.

The frontier settlement of Georgia was fraught with drama and conflict, from the infamous Yazoo land fraud that dominated state politics for much of the 1790s and beyond, to the gold rush in the north Georgia mountains in the 1830s, the most extensive and profitable gold rush east of the Mississippi River. It was on that frontier that the state founded, in a 1785 charter, the University of Georgia, the first university in the nation established by a state government. Sixteen years later the school opened its doors in the wilderness from which Athens later emerged. Another notable first was the establishment in 1836 of Wesleyan College in Macon, the first degree-granting women’s college in the world.

Along with Alabama and Mississippi, Georgia was home to a significant Native American populace for much longer than any other state along the Eastern Seaboard. While white Georgians were not alone in their conflicts with and ultimate removal of that native presence (in Georgia’s case, of the Creeks and the Cherokees), the tragic circumstances of the Cherokees’ forced exile from the state’s northwestern territory in 1838-39, known as the “Trail of Tears,” became a particularly potent symbol of the trauma and suffering that all such removals entailed. Georgia also had the distinction of being the only southern state challenged over Indian sovereignty in a U.S. Supreme Court case, Worcester v. Georgia (1832).

The construction of railroads connecting Athens, Augusta, Macon, and Savannah was another important development in Georgia during the 1830s. Atlanta, originally named Terminus, was founded in 1837 as the end of the rail system’s line and subsequently grew into one of the South’s principal cities. By the 1850s the state claimed more miles of rail lines than did any of its southern neighbors, positioning Georgia as an important home front during the Civil War (1861-65).

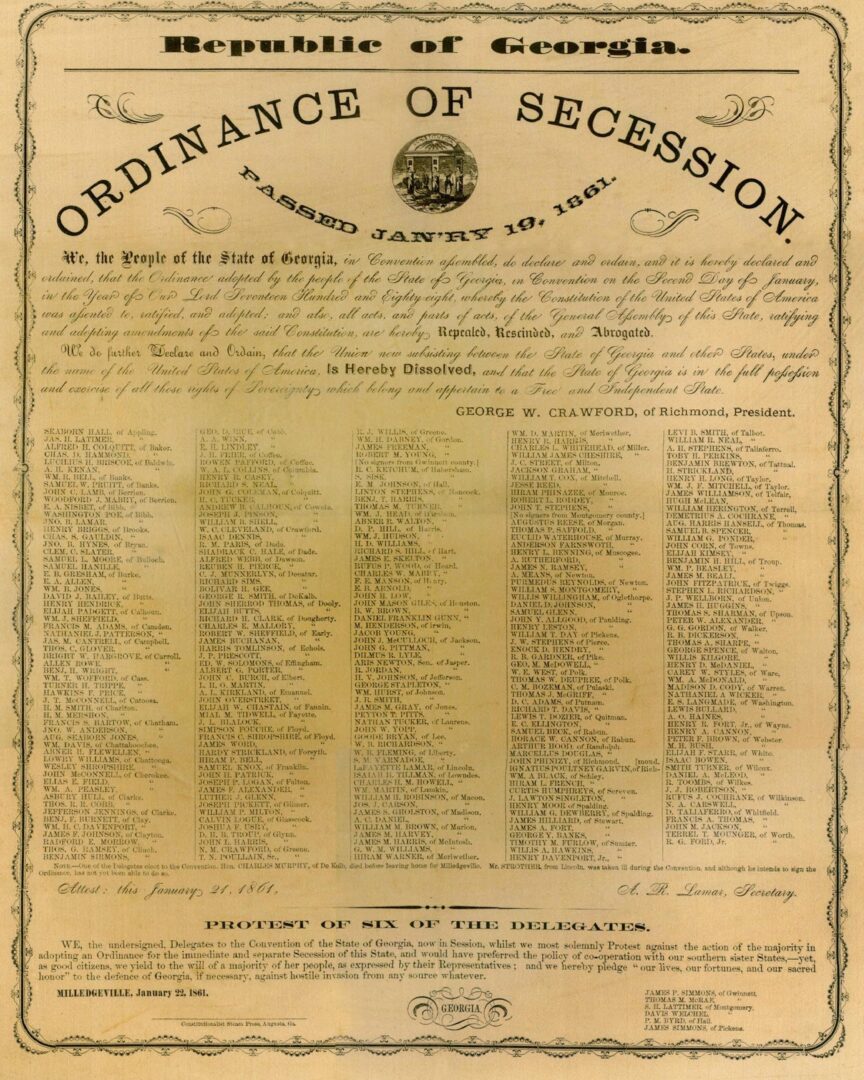

Civil War and Reconstruction

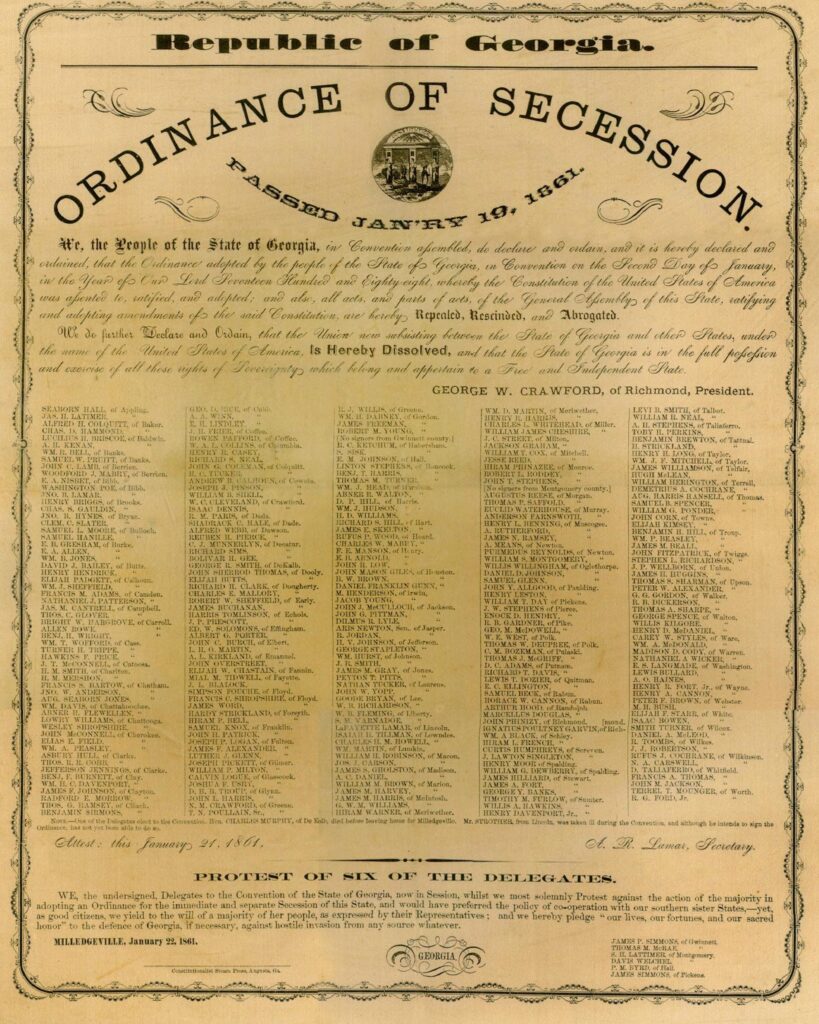

By 1860 the “Empire State of the South,” as an increasingly industrialized Georgia had come to be known, was the second-largest state in area east of the Mississippi River. (Only Virginia was larger, until its northwestern counties withdrew to form the separate state of West Virginia in 1863.) As both an Atlantic seaboard state and a Deep South state, Georgia played a particularly crucial role in the secession crisis and the formation of the Confederacy. It had the largest population and the largest number of both enslaved people and enslavers of any Deep South state (and was second only to Virginia overall), and yet it had two vast geographical areas in which slavery played only a minimal part—the southeastern wiregrass and longleaf pine woods region, and the northern mountains. Georgia became the fifth state to secede from the Union, on January 19, 1861, yet the state’s geographical diversity and the dominance of its nonslaveholding white populace made its selection of delegates to the 1861 secession convention one of the most divided (in terms of delegates for and against secession) within the first wave of southern states to leave the Union. The final vote to secede, however, was supported by a sizeable majority of those delegates.

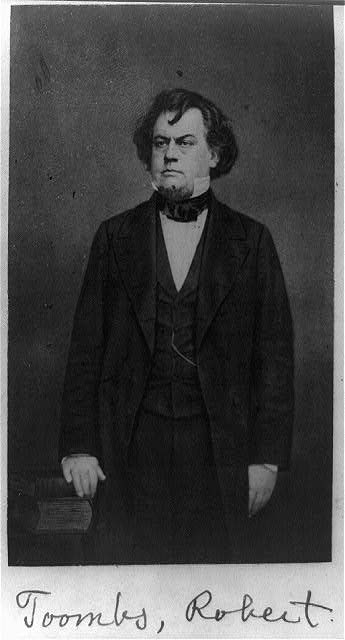

During the Civil War Georgians played a prominent role in the new Confederate government. Howell Cobb presided over the Confederacy’s organizing convention in Montgomery, Alabama, in February 1861, and his brother Thomas R. R. Cobb was the primary author of the Confederate Constitution. Alexander Stephens served as vice president throughout the Confederacy’s four-year existence, and Robert Toombs was its secretary of state. Paradoxically, Governor Joseph E. Brown was one of the most forceful governors (along with Zebulon B. Vance in North Carolina) to challenge the centralizing tendencies of Jefferson Davis’s administration in Richmond, Virginia.

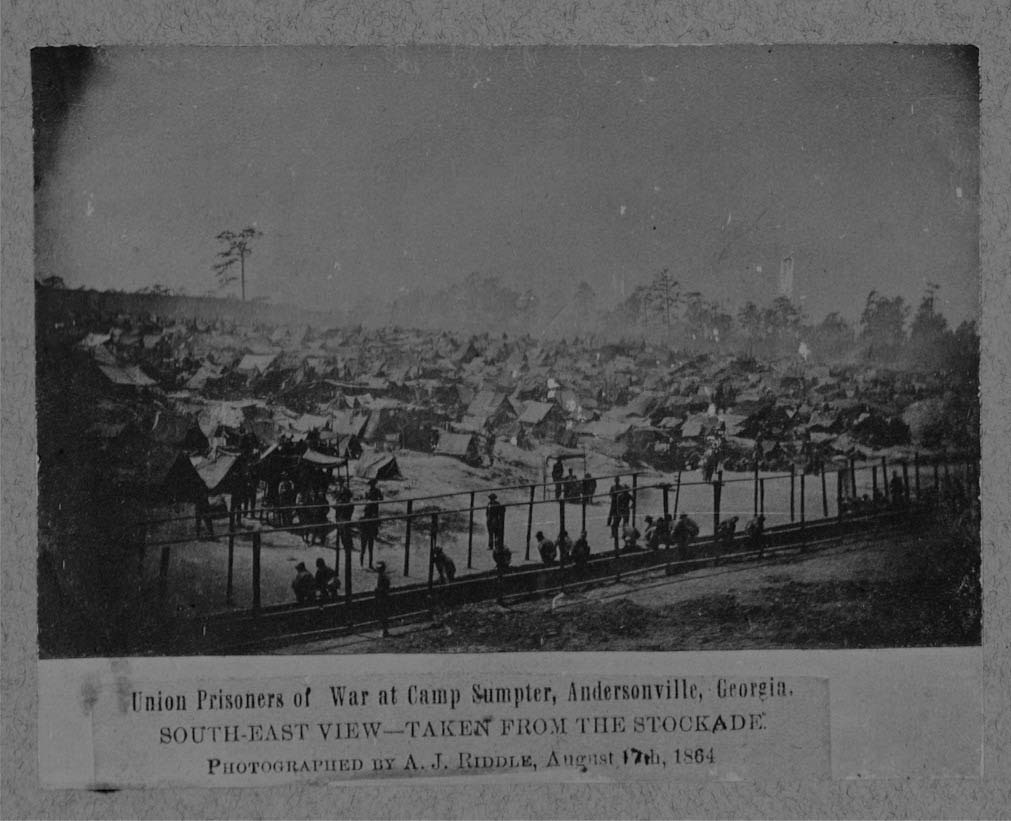

The most decisive military incursion into the Deep South occurred during Union general William T. Sherman’s campaign from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Atlanta in the spring and summer of 1864. The fall of Atlanta in September 1864, a major military and psychological setback to Confederate forces, secured U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s reelection less than two months later. Sherman’s subsequent military campaign, known as the March to the Sea, was an equally devastating blow to southern morale, capped by the December occupation of Savannah, which Sherman presented to Lincoln as a Christmas present. Another distinguishing feature of the war in Georgia was the presence of the prison camp at Andersonville, the largest and most notorious of the Confederate prison camps. Andersonville became the source of much postwar propaganda and notoriety due to the high casualty rate among its prisoners, and its commander, Swiss-born Henry Wirz, became a scapegoat for Northern anger as the only Confederate executed for war crimes.

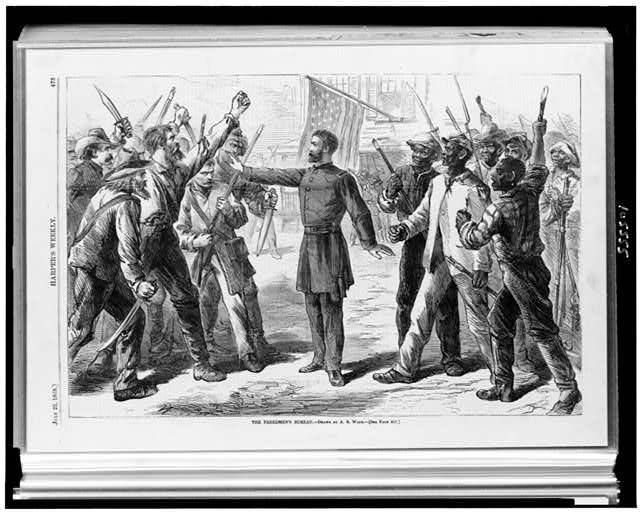

Georgians experienced Reconstruction much like the residents of other southern states. The postwar years were filled with political tensions, struggles over federal occupation, and racial violence, with both the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Ku Klux Klan playing as prominent a role in Georgia as in any former Confederate state. More than 460,000 enslaved people were freed in Georgia during and after the war. Sherman was still in Savannah when he issued Field Order No. 15, a radical plan for land redistribution to the emancipated Black populace. The Order, which offered what were ultimately false hopes to freedpeople throughout the South, provides the origin of the term “forty acres and a mule.”

Another notable aspect of Georgia’s Reconstruction was the General Assembly’s expulsion in 1868 of twenty-seven duly elected Black Republican legislators, despite the fact that Republicans then held both the governorship, in Rufus Bullock, and a majority in the state senate. That action, along with the subsequent Camilla Massacre, which left about a dozen Black protestors dead and thirty wounded, led the U.S. Congress to reimpose military rule to the state and to ban Georgia’s newly elected congressmen from taking their seats in the next House of Representatives. This action provided a strong lesson in federal power to other southerners who had hoped to subvert the federal law and constitutional amendments.

Although this setback made Georgia the last of the former Confederate states to be readmitted to the Union, with its congressmen finally seated on July 15, 1870, Reconstruction ended relatively early in the state. In late 1871 the state government returned to the full control of white conservative Democrats, known as “Redeemers,” thereby ushering in what white southerners once termed the “Redemption era.” At that time, several other southern states were still under Republican rule and military occupation, and would remain so for up to five more years.

The “New South” and Populism

The Redemption era in Georgia marked a return to power of several antebellum and wartime leaders, most notably the group known as the “Bourbon Triumvirate,” consisting of former Confederate governor Joseph E. Brown and former Confederate generals John B. Gordon and Alfred H. Colquitt. These three politicians maintained power within Georgia as governors and/or U.S. senators from 1872 until 1890, capitalizing on their positions to industrialize the state, often for their own profit. The triumvirate’s efforts were bolstered by Henry W. Grady, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, who spearheaded a crusade to build a prosperous “New South” centered around Atlanta. Using his considerable journalistic and oratorical skills, Grady fashioned an emotional portrait of Atlanta, which had replaced Milledgeville as the state capital in 1868, rising phoenix-like from the ashes of war to become the capital of a dynamic and progressive New South. The vision he articulated for much of the 1880s stood very much at odds with both the reality and the broad national impression of Atlanta, as well as the state at large, by the turn of the century.

Despite Grady’s vision, Georgia remained predominantly rural, with most of the state’s citizens attempting to survive as farmers. The loss of the slave labor force dealt a severe blow to cotton production, which, compounded by a decline in the demand for cotton worldwide, left Georgia agriculture in dire financial circumstances. Neglected by a government focused on industrial and business opportunities, farmers had no choice but to participate in the tenant and crop lien systems, which imposed an exploitative and stifling credit system. By 1880 45 percent of Georgia’s farmers, Black and white, had been driven into tenancy, and by 1920 two-thirds of farmers worked on land they did not own, most often as sharecroppers.

The rise of the Farmers’ Alliance and the Populist Party in Georgia during the late nineteenth century allowed farmers to protest the situation. Formally organized in 1892, the Populist Party, under the leadership of Thomas E. Watson, offered a platform of banking and railroad reform, as well as cooperative farm exchange. For many elite white and politically entrenched Georgians, the true danger of Populism lay not in its economic policies but in its racial inclusiveness, as Black farmers were encouraged to participate in the new third-party movement.

Watson championed this biracial alliance, and he achieved national status as a Populist leader, gaining the party’s nomination for vice president in 1896, thereby becoming the first Georgian to run on a national ticket since William Harris Crawford in 1824. Even as Watson received this recognition, however, the Populists lost ground nationally when the Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, co-opted their advocacy of the unlimited coinage of silver. Ultimately, the election was lost to the Republican candidate William McKinley.

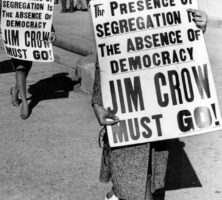

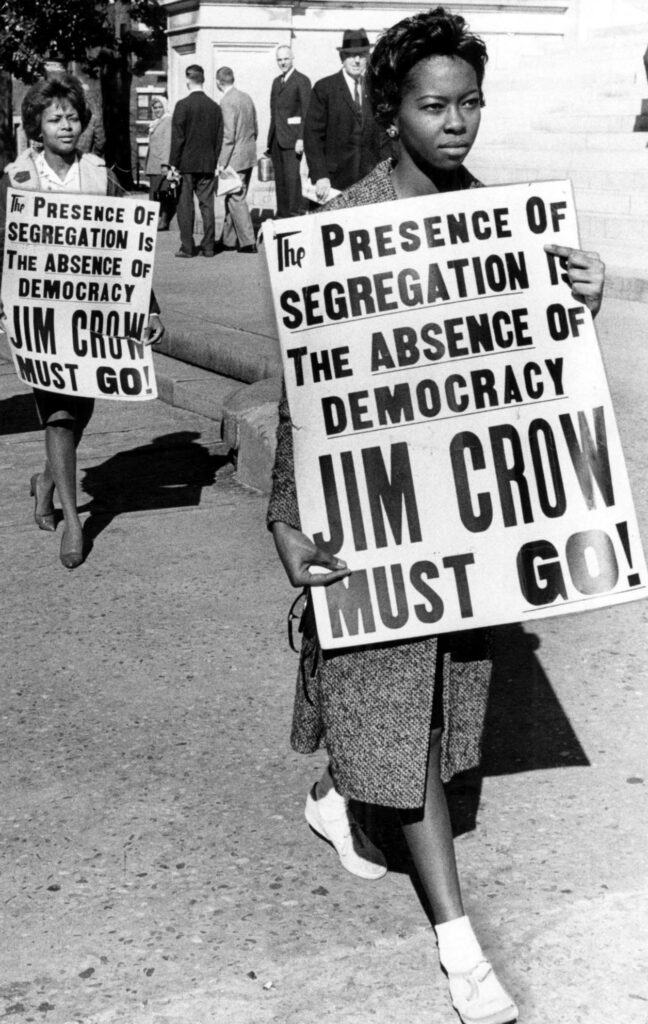

Jim Crow

The demise of the Populists had consequences in Georgia (and across the South) that extended beyond their failure as a third party. In the wake of Populism’s unsuccessful efforts to challenge the established racial hierarchy, reactionary heirs of the Bourbon Triumvirate worked to curtail the political power of Black voters, as well as to formalize the convention of social segregation. In 1908 an amendment to the state constitution established literacy and property requirements to supplement the poll tax, effectively barring voting by Blacks, and many poor whites as well. This disfranchisement, along with legislatively mandated racial segregation of public facilities, defined the Jim Crow era that would prevail in Georgia and the South for more than half a century.

At the same time, the suppression of Black citizens took a far more violent turn. More lynchings took place in Georgia between 1889 and 1918 than anywhere else in the United States, and Atlanta cringed in the aftermath of a brutal, three-day race massacre in September 1906. While most lynchings were racially motivated, the most notorious was that of Leo Frank, a Jew, who was taken from prison in August 1915 by a mob and hanged near Marietta after being convicted of murdering Mary Phagan, an Atlanta pencil factory worker. A few months later the Ku Klux Klan was ceremonially resurrected atop Stone Mountain. National attention to both the Leo Frank lynching and the rebirth of the Klan seriously damaged Georgia’s image, with further evidence of its benightedness brought on two decades later by three best-selling books: I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! (1932), a memoir by Robert E. Burns; and Erskine Caldwell’s novels Tobacco Road (1932) and God’s Little Acre (1933).

The Great Depression and World War II

Meanwhile, for all the talk of progress and prosperity emanating from Atlanta and other cities, conditions in the countryside went from bad to worse. The boll weevil became a major problem upon its introduction to the state in 1915 and led to a precipitous drop in cotton production, with the number of bales produced in 1923 only about a fourth of the number produced five years earlier. During the 1920s more than 400,000 residents, almost all Black, migrated to other parts of the country, and between 1910 and 1930 nearly half the state’s agricultural workers had abandoned farming.

The Great Depression and the New Deal policies imposed to remedy its effects were equally transformative in their impact on Georgia agriculture. U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt was fully familiar with the plight of rural Georgians from his years of polio treatments at Warm Springs, both prior to and throughout his presidency. Inaugurated in 1933, Roosevelt created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration during his first 100 days in office as an attempt to raise crop prices by lowering agricultural production. An unintended consequence of the policy, however, was to put farmers out of work, causing even greater numbers to seek other means of employment. As a result, rural communities struggled to maintain their populations in the face of dwindling farming income and the lack of industrial job opportunities. Promising a surplus of cheap, nonunion labor and relying on a variety of inducements, some of which were financed by public subscription or deductions from workers’ checks, several Georgia towns succeeded in attracting small, low-wage employers—mostly textile mills —in the 1930s.

The state’s unique aviation history also began during these years, and set the stage for Georgia’s later industrialization and economic prosperity. Ben Epps, considered to be the father of aviation in the state, built and flew the first plane in Georgia on a field in Athens in 1907. In 1923 acclaimed aviator Charles Lindbergh flew his first solo flight at Souther Field in Americus, and two years later William B. Hartsfield, who later became mayor of Atlanta, established Hartsfield Airport (later Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport). Within a few decades, the airport served as a major hub for both Eastern Air Lines and Delta Air Lines, which moved its headquarters to Atlanta in 1941.

The United States’ entry into World War II (1941-45) brought the Great Depression to an end, as industrial production for the war effort created thousands of new jobs around the nation. Georgia in particular felt these economic benefits, as soldiers arrived for training at Fort Benning (now Fort Moore) in Columbus, at that time the largest infantry training post in the world. The Bell Aircraft Corporation in Marietta, known as Bell Bomber, produced B-29 airplanes from 1943 until the end of the war, and by early 1945 the factory employed more than 28,000 workers. The ports of Savannah and Brunswick produced nearly 200 “Liberty Ships” between 1942 and 1945. The Southeastern Shipbuilding Corporation, based at a site on the Savannah River, employed more than 15,000 workers.

The economic effect of such war activities across Georgia was significant, with annual personal income rising from less than $350 in 1940 to more than $1,000 by 1950, surpassing the national average. After the war the state continued to prosper, with Atlanta in particular experiencing a growth in industry and population. A transportation hub since its origins as a railroad town, the city was well positioned to accommodate this growth with the development of Hartsfield Airport from a regional facility into a national airport during the 1950s and 1960s. (By the late twentieth century Hartsfield had become one of the busiest passenger airports in the world.)

The Civil Rights Era and Sunbelt Georgia

As the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s unfolded, the interests, aims, and ambitions of Atlanta’s political and economic leaders diverged dramatically in many ways from those that prevailed in the state at large. As the city’s population surged, Atlanta voters chafed under the state’s county unit system, which gave, for example, three rural counties with a combined population of 7,000 just as much clout in statewide elections as Fulton County, with its 550,000 inhabitants. The result was that the more racially moderate and economically progressive candidates generally favored by Atlantans had to fight an uphill battle against self-styled rustics and race-baiters like Eugene Talmadge, who won the governorship four times in the 1930s and 1940s without, as he bragged, ever campaigning in a county with streetcars. Talmadge dominated the state’s political scene until he died as governor-elect in 1946, precipitating the bizarre and embarrassing three governor’s controversy.

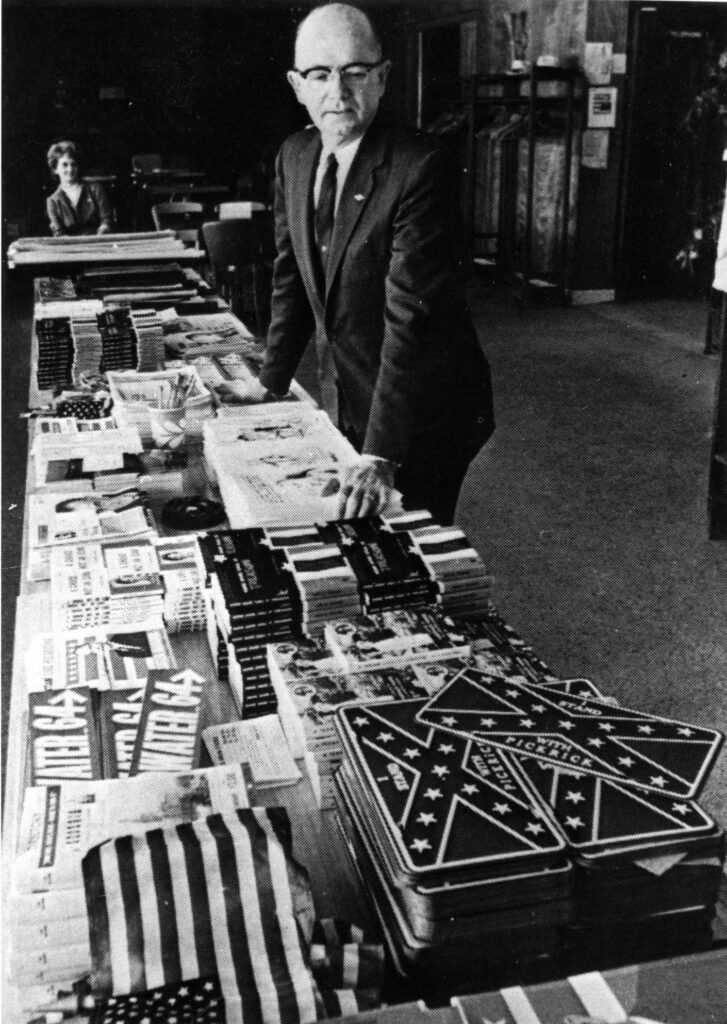

In 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that the “separate but equal” laws governing public education in Georgia and other southern states were unconstitutional. Although some Georgia politicians and citizens advocated closing the schools rather than abiding by the court’s decision, and although the decision prompted the inclusion of the Confederate battle flag in the state flag redesign of 1956, the money and power accumulating in Atlanta finally asserted itself in 1960. That year the state’s avowed segregationist governor, Ernest Vandiver Jr., appointed influential Atlanta lawyer and banker John A. Sibley to chair a special legislative committee to study the matter. Although 60 percent of witnesses who spoke at the hearings favored statewide school closings, Atlanta’s civic and business leaders believed this route meant economic disaster for their city. They convinced the Sibley Commission to recommended a local option on the matter.

Similar pressure from Atlanta’s growth-oriented elite played a key role in dissuading Governor Vandiver from closing the University of Georgia when the courts ordered the admission of two Black students, Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter, in January 1961. Despite some resistance on the part of students and protests from around the state, the university’s integration went far more smoothly than was the case at either the University of Mississippi, in 1962, or the University of Alabama, in 1963.

In 1962 the federal district court struck down the county unit system, unloosing Atlanta’s massive political influence on a state accustomed to what one observer called “the rule of the rustics.” Although Atlanta avoided the ugly confrontations that drew attention to the cities of Little Rock, Arkansas, and Montgomery and Birmingham, Alabama, it remained a crucial center for the civil rights movement, serving as the base for native son Martin Luther King Jr. and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) also established a strong presence in the state, most notably in the Albany Movement of 1961-62. The confrontation between Albany’s law-enforcement officers and a coalition of local Black leaders, with the support of both the SCLC and SNCC, was considered the first grassroots effort to challenge desegregation on all fronts. The Albany Movement was also notable as the first such movement in which King participated after the Montgomery bus boycott, and it served as a precursor to the much larger mobilization of the movement in Birmingham in the spring of 1963.

In the wake of these developments, racial moderate Carl Sanders was elected governor in 1962 and worked during his term in office to bring Georgia into compliance with federal civil rights law. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed by U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson, forever altered the political landscape of the state, with the number of registered African American voters doubling between 1960 and 1970. The number of Black elected officials also rose dramatically during these years, from three in 1962 to thirty by the end of the decade. By 2000 more than 600 African American officials held office in Georgia.

The civil rights movement was largely implemented by the Democratic Party, which led to Georgia’s white electorate breaking with the national party for the first time in the twentieth century. The so-called Solid South came to an end in the presidential election of 1964, as Georgia voters (like those throughout the South) gave conservative Republican Barry Goldwater 54 percent of their vote, thus repudiating the incumbent, President Johnson. A southern Democrat himself, but a champion of civil rights, Johnson won reelection in a national landslide. In 1966, when Sanders declined to run for a second term as governor, segregationist Lester Maddox won a surprising gubernatorial victory in Georgia, clearly demonstrating that many whites in the state continued to resist the social and political transformations of the era.

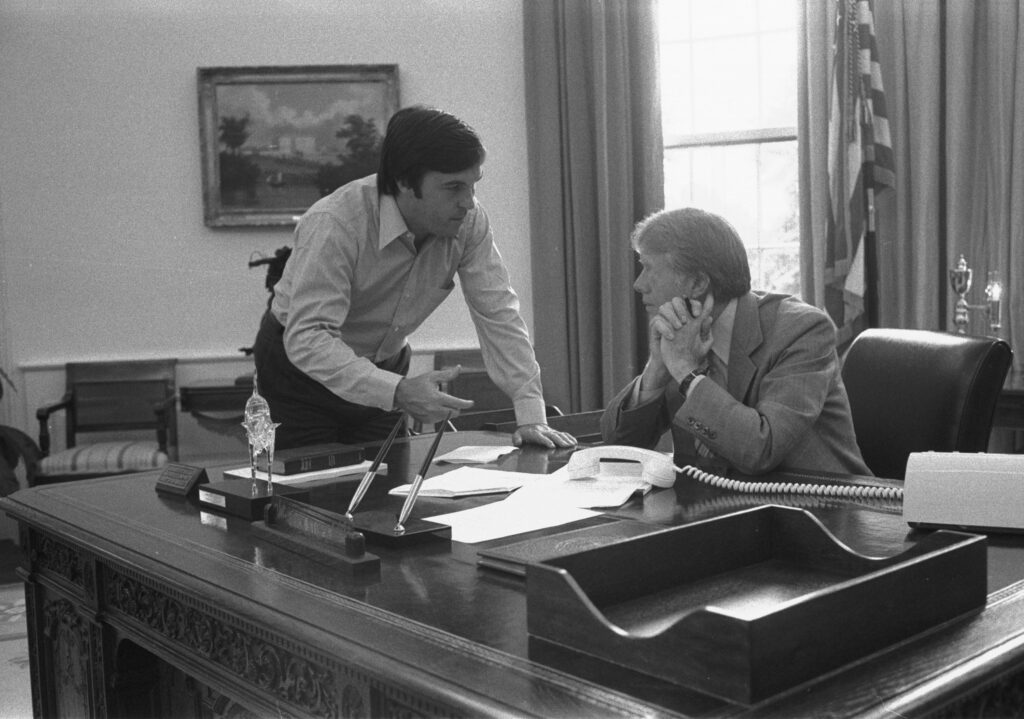

This shift toward the Republican Party continued both in Georgia and throughout the South. In subsequent presidential elections a majority of Georgia voters cast ballots for Republican candidates, with only two exceptions. Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, carried the state and the nation in 1976; he carried the state again in 1980, although he lost the election to Republican Ronald Reagan. Notably, Carter won a majority of the state’s Black vote but not the white, as did Arkansas native and presidential candidate Bill Clinton in 1992, demonstrating the continuing legacy of Black political power engendered by the civil rights movement.

During the last three decades of the twentieth century, metropolitan Atlanta proved to be the heart of the Sunbelt, a term applied to the economic and demographic resurgence of the southernmost swath of the country in the years following World War II. Atlanta continued to expand both in size, as its borders sprawled into surrounding counties, and in influence at the state and national levels. The international delivery corporation United Parcel Service moved its headquarters to Atlanta during these years, while such homegrown entities as Coca-Cola, The Home Depot, and Turner Broadcasting (including CNN) thrived beyond the state’s borders. In 1996 Atlanta hosted the Centennial Summer Olympic Games, further raising the city’s profile and creating a lasting physical legacy through the construction of such venues as Centennial Olympic Park and other infrastructure improvements.

The carpet and poultry industries of north Georgia achieved national prominence as well, while the agricultural regions in the southern counties maintained the state’s reputation as a major producer of peaches, peanuts, and Vidalia onions. Farming, however, declined as a major occupation in Georgia, as smaller farms were subsumed by larger operations. The total farm population shrank from roughly 1 million in 1950 to around 63,000 in 2000.

Developments in the Twenty-first Century

In state politics white support for Democrats eroded steadily in the twenty-first century as Republicans rode their presidential momentum to victories further down the ticket. In 2003 Sonny Perdue became the first Republican governor since Reconstruction, and he easily won reelection in 2006. By 2009 the Republican Party controlled both houses of the General Assembly, and both of the state’s U.S. senators were Republican, as were seven of its thirteen members of the U.S. House of Representatives. In 2008 Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama made a strong showing in Georgia, especially among Black voters, although he ultimately did not carry the state.

Georgia’s economy experienced significant shifts in the first decade of the twenty-first century, as manufacturing jobs, particularly in the state’s rural counties, moved overseas. Between 1997 and 2005 alone, rural counties bore the brunt of some 98,000 job losses in manufacturing, the bulk of them concentrated in the textile and apparel industries. Agricultural work, conversely, brought thousands of immigrants, particularly Latinos, to the state, many of whom also found employment in the service and construction industries. But with the beginning of a national economic recession in 2008, many left to seek jobs elsewhere. The recession also led to severe budget cuts in 2008 and 2009 that affected government services, including education, around the state.

Georgia experienced a significant drought mid-decade and engaged in protracted battles with neighboring states Florida and Alabama over access to water, much of which was being diverted to support the continually expanding Atlanta metropolitan area. After adding nearly 900,000 residents between 2000 and 2006 alone, Atlanta surged past both Boston, Massachusetts, and Detroit, Michigan, to become the nation’s ninth-largest metropolitan area, covering twenty-eight counties by 2007. The city continues to generate a significant portion of the state’s income but also deals with ongoing issues of poverty, particularly among its inner-city African American population. Poverty, exacerbated by the economic downturn, plagues many rural counties as well.

Despite such challenges, Georgia continues to attract new opportunities for employment. Kia Motors Corporation, a Korean automobile manufacturer, broke ground on a factory in Troup County in 2006; major employer Delta Airlines emerged successfully from bankruptcy in 2007; and new tax-incentive legislation for the entertainment industry, passed in 2008, brought numerous film projects to the state. Georgia’s unique landscapes and culture support a thriving tourism industry as well.