The Savannah River, one of Georgia’s longest and largest waterways, defines most of the boundary between Georgia and South Carolina. The river originates at the confluence of the Seneca and Tugaloo rivers in Hart County in eastern Georgia. The confluence also forms Lake Hartwell, a large reservoir built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Though the Savannah itself begins in the Piedmont geologic province, its tributary headwaters originate on the southwestern slopes of the rugged Blue Ridge geologic province of Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Only about 6 percent of the Savannah’s entire drainage basin, however, lies within the Blue Ridge. The rest lies in the Piedmont and in the Upper and Lower Coastal Plain provinces.

On a map, the basin roughly resembles an arrowhead. It encompasses 10,577 square miles, of which 175 square miles are in southwestern North Carolina, 4,581 square miles are in western South Carolina, and 5,821 square miles are in eastern Georgia. In Georgia, the basin drains portions of twenty-seven counties.

From Lake Hartwell, the Savannah River flows southeasterly for 313 miles across the Piedmont and the Upper Coastal Plain until it empties into the Atlantic Ocean approximately 15 miles downstream from the city of Savannah. As such, the Savannah is an alluvial stream, meaning that its waters originate in the mountains and the Piedmont and flow across the Coastal Plain to the ocean. The alluvial rivers transport large amounts of sediments, which contribute to the sand deposits on coastal islands, and of nutrients that nourish life in the river.

At the U.S. Geological Survey river gauge near Clyo, in Effingham County, the Savannah’s average annual flow is 12,040 cubic feet per second, one of the largest discharges of freshwater from any river in the Southeast. (One cubic foot equals about 7.4 gallons.) The gauge at Clyo, approximately sixty-one miles upstream of the mouth of the Savannah, is the most downstream gauge that records river discharges. Below this point, the Savannah is tidally influenced, and conventional river-flow measurement is unreliable.

On its journey to the sea, the Savannah flows through forests, agricultural lands, large hydroelectric reservoirs, and extensive swamps. It is known for its high bluffs, some of which were the locations of prehistoric Native American villages.

The river provides drinking water to two of Georgia’s major metropolitan areas, Augusta and Savannah, and assimilates their treated wastewater. It is also a source of drinking water for the cities of Beaufort and Hilton Head in South Carolina and for many smaller municipalities in the basin. In addition, the Savannah supplies water for the Savannah River Site, which includes the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, in South Carolina, as well as for the two nuclear reactors of Plant Vogtle, a major electricity-generating facility operated by Georgia Power Company in Burke County.

On the coast, the Savannah River is the shipping channel for the Port of Savannah, the nation’s tenth-busiest port for oceangoing container ships, which is operated by the Georgia Ports Authority. Before emptying into the Atlantic, the Savannah forms a braided network of tidal creeks, salt marshes, and freshwater marshes, much of which constitutes the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge, one of Georgia’s prime bird-watching spots.

Path to the Sea

Upper Section

The stretch of river north of Augusta is known as the upper Savannah, along which is located Lake Hartwell, the first of three large lakes built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The other two are Lake Richard B. Russell and Clarks Hill Lake. The reservoirs regulate the river’s flow and provide hydroelectric power, flood control, recreation, and drinking-water storage. The 56,000-acre Lake Hartwell, about 90 miles north of Augusta, was completed in 1963. The 26,650-acre Richard B. Russell Lake, just downstream from Hartwell, was finished in 1983. The 71,535-acre Clarks Hill Lake (known as J. Strom Thurmond Lake in South Carolina), downstream from Russell and 22 miles north of Augusta, was created in 1954.

The Savannah’s major tributaries in the upper stretch are the Broad and Little rivers, which flow into Clarks Hill Lake. Downstream from Clarks Hill Dam, the middle section of the Savannah begins. This section is located partially in the Piedmont but is predominately in the Upper Coastal Plain. Shortly after flowing out of Clarks Hill, the river runs through a series of shoals. Just above Augusta, river water is partially diverted into the Augusta Canal. Water in the canal, used for power and water supply, feeds back into the Savannah River at various locations.

Middle Section

In the middle section of the Savannah, wide flood plains and wetlands begin to emerge along the waterway. A notable feature is the eighty-four-acre Savannah River Bluffs Heritage Preserve, just outside the city of North Augusta in Aiken County, South Carolina. The preserve contains one of the few remaining river shoals in the Savannah River. Rock formations that may be remnants of ancient Native American fishing weirs occur in the waterway here.

In Augusta the Savannah River passes through a heavily industrialized area of chemical plants and other facilities that discharge treated wastes into the river. About thirty-five miles downstream from Augusta, the huge twin cooling towers of the Vogtle nuclear plant loom along the river in Burke County. In 1983 fossilized whale bones dating back 40 million years were discovered during plant construction.

Across the river from Plant Vogtle, in South Carolina, sits the U.S. Department of Energy’s 310-square-mile Savannah River Site, whose five reactors churned out tons of radioactive plutonium and tritium for thermonuclear weapons from the 1950s through the 1980s. The site once sucked hundreds of millions of gallons each day from the Savannah to cool the reactors, which are no longer in operation. The site still uses water from the river for other purposes.

Also in the middle stretch is Shell Bluff, a scenic and noteworthy bluff just south of the fall line in Burke County. A nearly vertical face rises more than 100 feet directly above the river. The cliff-like face is chalky white, due to material weathered from limestone. The presence of giant fossilized oyster shells here is evidence that the fall line formed a coastline some 50 million years ago. The naturalist John Bartram, father of William Bartram, visited Shell Bluff in 1765 to study the large shell formation.

Lower Section

Farther downstream, in Screven County, Brier Creek is the Savannah’s only major tributary south of Augusta. The confluence marks the beginning of the lower Savannah. In general, the lower Savannah (to the place where Interstate 95 crosses the river) encompasses a more pristine environment, with oxbow lakes, extensive river swamps, bottomland forests, and blackwater tributaries.

The Savannah River is generally navigable from Augusta to Savannah, a distance of approximately 200 miles. The waterway was formerly maintained for navigation by the Corps of Engineers. In the late 1950s through the early 1960s, the corps constructed thirty-eight cuts across meander bends, shortening the river by seventy-eight miles to provide a more direct route to the sea. Nevertheless, by 1980, shipping on the river between Augusta and Savannah had virtually ceased. Channel maintenance between the two cities was discontinued. Today, due to the lack of commercial traffic, the corps is considering a project to restore the meanders and dismantle the New Savannah Bluff Lock and Dam.

About twenty-eight miles upstream from where the Savannah enters the Atlantic Ocean, saltwater begins mixing with the river’s freshwater to form an estuary. Past the Interstate 95 bridge the estuary becomes a complex, tidally driven system of deltaic channels as the Savannah splits into three forks: the easternmost Back River, the centrally flowing Middle River, and the western Front River. At the city of Savannah, the split-up river, now an estuary, enters into its most heavily used stretch. It is used for several purposes, including a major industrial complex, the Savannah harbor, and the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge. The Savannah River estuary has been heavily contaminated over the years with sewage and industrial wastes, but these pollutants have been reduced considerably in recent years.

The Back and Middle rivers, relatively narrow and shallow streams, sustain the 29,000-acre wildlife refuge. The refuge and surrounding area contain 21 percent of the tidal freshwater marsh—much of it former rice fields—in South Carolina and Georgia and 28 percent of the freshwater marsh along the eastern coast of the United States. The Front River, the Savannah’s largest channel, has been extensively widened and deepened to provide deep-water shipping access for the Port of Savannah. At present, the shipping channel extends approximately twenty-one miles inland from the mouth of the Savannah. Periodic dredging keeps its maximum depth to forty-two feet.

Below the city of Savannah, the river picks up more of the characteristics of a tidal river, with more treacherous currents, saltier water, and extensive expanses of salt marsh dominated by the plant Spartina alterniflora, or smooth cordgrass. In this area the river exhibits one of the highest tidal ranges on the U.S. East Coast; the difference between low tide and high tide can be more than seven feet.

Ecology and Biological Resources

From its beginning as a clear, cool, free-flowing stream in the Blue Ridge Mountains to its end as a coastal estuary, the Savannah River and its tributaries sustain some of the world’s most diverse and biologically rich ecosystems. The Nature Conservancy of Georgia describes the Savannah River basin’s abundant diversity of life as rivaling that of a South American rain forest. The natural splendor attracted many early naturalists, including eighteenth-century explorers Mark Catesby and John and William Bartram, who marveled over the basin’s flora and fauna.

The basin’s forest types range from mixed deciduous and evergreen forests in the Blue Ridge and Piedmont to coastal maritime forests dominated by spreading live oaks in the Lower Coastal Plain. Bottomland forests, stretching for miles on either side of the river south of Augusta, harbor towering cypress and tupelo trees. Other typical river-swamp species include such canopy trees as green ash, overcup oak, swamp black gum, and water hickory, and such understory flora as saw palmetto, swamp dogwood, and swamp palm.

The basin is home to more than seventy-five species of rare plants and animals, including the majestic swallow-tailed kite, the rocky shoals spider lily, and the wild cocoa tree. On river bluffs near Augusta, such rare plants as bottle-brush buckeye, false rue anemone, and relict trillium can be found.

The Georgia and South Carolina Heritage programs list eighteen fish species in the basin as species of concern because of their limited populations. Most notable are the robust redhorse (Moxostoma robustum), previously believed to be extinct but documented in the middle section of the Savannah in 1997, and the federally endangered shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum), of which only about 3,000 are known to exist in the Savannah River.

In total, more than 110 fish species have been documented in the Savannah basin. Both wild and stocked rainbow trout and brown trout are the principal sport fishes in the upper reaches of the Tallulah and Chattooga rivers. Some headwater areas contain reproducing populations of native brook trout.

The fish communities of the headwater streams change rapidly from cold-water to warm-water species in response to decreasing elevations and increasing water temperatures. The largest group of species belongs to the sucker family. Warm-water species include American shad, black crappie, bluegill, chain pickerel, channel catfish, largemouth bass, redbreast sunfish, redear sunfish, striped bass, and white bass.

A diversity of reptiles and amphibians lives in the Savannah basin, including the American alligator; nonpoisonous snakes like the coachwhip, rat, rough green, and speckled king; poisonous snakes like the eastern cottonmouths, rattlesnake, and southern copperhead; several species of frogs and turtles; and numerous species of lizards and salamanders, including the endangered flatwoods salamander and striped newt.

The lower Savannah’s blackwater tributaries are of exceptional biological value, providing outstanding habitat for a high number of vertebrate and invertebrate species. Of special note is Ebenezer Creek in Effingham County, upstream from the city of Savannah. Ebenezer is one of Georgia’s four designated Wild and Scenic Rivers, and the only one on the coast. It is also designated a National Natural Landmark. Ebenezer’s swamp consists of unusual virgin bald cypress, with huge swollen buttresses eight to twelve feet wide, which support tree trunks of unusually small diameters. Some of the trees are estimated to be more than 1,000 years old.

Human History

The Savannah River’s banks are steeped in human history. Portions of the river flow through the sites of some of the most important archaeological digs in the United States. Some of those projects took place in the 1960s in what is now Lake Russell, before it was filled with water.

Archaeologists believe that the Paleoindians first appeared along the Savannah River near the end of the Ice Age, some 12,000 years ago. Clovis points, or stone projectiles used by Paleoindians for hunting, have been found along the Savannah. About 4,500 years ago, in the late Archaic era, crude pottery appeared near the river. Some of the oldest pottery in North America was discovered at Stallings Island, a National Historic Landmark located in the Savannah eight miles upstream from Augusta.

The first-known European explorer to reach the Savannah was Hernando de Soto in 1540. He and his soldiers crossed the river, probably near what is now Augusta, where the river divided and swept around an island. In the late sixteenth century the French started the first European commerce on the Savannah, trading with the Indians for sassafras. Sassafras may have triggered the first naval battle on the river. In 1605 the Spanish, who claimed ownership of the New World territory, came upon a group of French traders on the river and defeated them in a bloody battle.

Some time during the early seventeenth century, the Westo Indians took up residence along the Savannah. They became allies of the English in South Carolina and acted as a buffer against the Spanish to the south. The English traded guns and cloth with the Indians for furs and deerskins. Deerskins were shipped by pack trains and flatboats down the Savannah and around the inland waterway to Charleston, South Carolina, and thence to England.

In the early 1700s growing tensions between the British in South Carolina and the Spanish in Florida prompted the British to establish another colony on the river to buttress the Carolina settlement. In 1733 James Edward Oglethorpe chose a forty-foot-high bluff on the Savannah, eighteen miles upriver from the ocean, as the site of Georgia’s first town, Savannah. One year after Savannah’s founding, German Lutherans seeking religious freedom sailed thirty miles up the river to establish the town of Ebenezer. In 1736 Oglethorpe established Augusta; his choice of the upriver location was influenced by profitable trade with the Indians.

The Savannah settlement discovered that the marshlands around Savannah were ideal for the cultivation of a particular staple—rice. In the early years of the colony, rice plantations dotted the riverbanks and marshlands, whose waters, fed by the river and the tides, allowed for a rapid prosperity.

When the American Revolution (1775-83) erupted, the patriots quickly saw the strategic importance of the Savannah. Twelve stockade-type forts were already located along the waterway to protect against Indian attacks when the war began. Most of the forts were strengthened when hostilities with the British heated up around 1776. The economic importance of the Savannah River to Georgia was reflected in the state’s original Constitution of 1777. Four of the eight original counties established by the constitution were located along the Savannah—Burke, Effingham, Richmond, and Wilkes. The other four counties were along the coast.

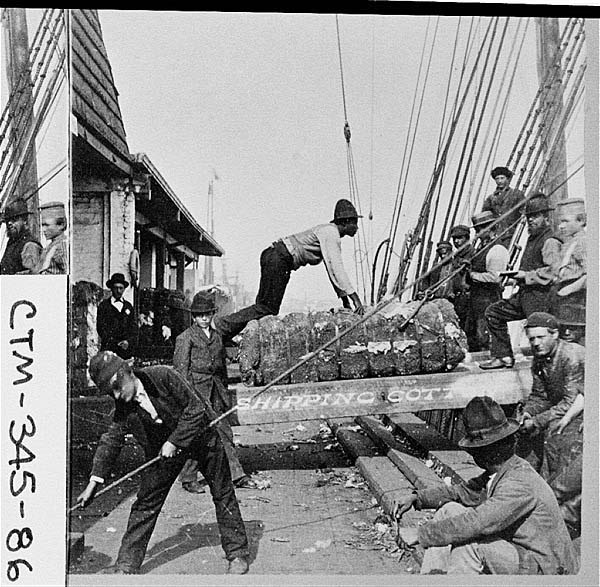

After the Revolutionary War, rice continued to be a major crop. But in 1793, at Catharine Greene’s plantation on the banks of the Savannah, just upstream from the city, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin. In short order, cotton dominated the region completely. The central sections of Georgia and South Carolina, including the areas bordering the Savannah, became the main cotton-producing region for the entire country. Intense plowing practices caused topsoil to erode and wash off into the Savannah and its tributaries, choking the life out of many of them. In November 1808 the first steamboat appeared on the Savannah, and soon the vessels became regular sights on the river between Savannah and Augusta, as they hauled cotton to markets in Savannah.

Early in the Civil War (1861-65), the Union blockaded the river and strangled the Port of Savannah. After the war, cotton shipping resumed on the river, but by the 1890s, a declining market and the arrival of the boll weevil greatly reduced the amount of the product going downriver. By that time two other products, naval stores and lumber, were in high demand. Countless trees in the swamps and forests along the Savannah were felled and floated downstream in huge log rafts to satisfy the lumber industry’s voracious appetite. After a time, the floating rafts of timber were about the only activity on the river; the steamboats had given way to railroads.

In 1915 representatives of the sugar industry selected a site several miles upriver from Savannah for a sprawling sugar plant that could be reached by oceangoing freighters in the river. A channel to accommodate ships was opened in 1917, paving the way for Savannah to become a major port. In 1945 the Georgia Ports Authority was formed, and the river was dredged to thirty-eight feet. In 1994 the channel was deepened to forty-two feet. In May 2014 the U.S. Congress passed legislation providing funds to dredge the river to forty-seven feet, allowing the port to accommodate larger oceangoing vessels.

Environmental Concerns

Despite the river’s scenic beauty and natural diversity, the ecological health of the Savannah River system—from the headwaters to the estuary—is declining, according to the Nature Conservancy of Georgia, which regularly monitors the river system.

The huge dams and reservoirs on the upper Savannah have negatively altered the river’s natural flow patterns, which support the basin’s diversity of wildlife. Impoundments, for instance, have changed and interrupted the natural hydrologic patterns of Ebenezer Creek, causing concern for the health of the blackwater stream. The Corps of Engineers has experimented with altering water-release patterns from Clarks Hill lake to determine whether high-flow releases could help the swamp.

In addition, large-scale timbering, municipal water needs, and harbor-dredging and expansion are contributing to the degradation of the entire ecosystem, according to the Nature Conservancy. Environmentalists contend that each dredging of the Savannah harbor affects the estuary’s freshwater-saltwater composition, impacting the flora and fauna of surrounding marshes.

Legions of anglers, for instance, were once attracted by the abundant populations of striped bass found in the Savannah. But saltwater intrusions from dredging to increase river depth, along with a tide gate built on the Back River in the 1970s, increased salinity levels, which decimated 98 percent of the fish’s eggs. Officials have stopped using the tide gate, and striped bass populations are recovering.

Communities along the Savannah also are concerned about the water supply in the river. They want to make sure that the river will provide clean water for drinking and for recreational and industrial use, even during drought. In 2005 Georgia and South Carolina started formal talks over sharing the Savannah’s water. Another concern is that Atlanta, about 150 miles west of the Savannah River, will try to take water from the river when the metropolitan area’s water sources reach their capacity by 2030. A similar concern is that the Greenville-Spartanburg area in South Carolina takes millions of gallons of water out of the Savannah basin but does not return treated water to the basin.

In addition, saltwater intrusion in the Floridan aquifer, a honeycomb of underground lakes underlying much of south Georgia, has forced coastal communities in both Georgia and South Carolina to depend more on the Savannah for drinking water and industrial needs.

Environmentalists predict that as the Savannah basin experiences population growth, industries and towns that discharge treated wastewater into the river will have to find ways of reducing their pollution to make more water available for human consumption. Industries and towns on the Georgia side of the river account for 90 percent of the wastewater discharges into the river from Augusta to the ocean. New development and population growth itself threaten the river basin’s water quality as well. For instance, environmental authorities are concerned that growth around the reservoirs on the upper Savannah will degrade the water quality of the lakes, especially that of Lake Hartwell along the Interstate 85 corridor.

Communities downstream of the Savannah River Site are concerned about the plant’s releases of radionuclides, including tritium, cesium, and strontium, into the river. Health officials consider the low dosages of radionuclides to be safe, but the communities are concerned that accidental releases of higher levels could contaminate drinking water. Another pollutant is mercury, which appears to come primarily from coal-fueled power generation and the manufacture of chlorine for bleach. Mercury contaminates fishes and the people who consume them.